Ask the eldest son of comedy and civil rights legend Dick Gregory why he only has one name and he’ll tell you it was because his father didn’t want him to be drafted. It was 1967, the Vietnam War had raged for more than a decade with no signs of letting up, and so Gregory the elder named his son, simply, Gregory. No first name, no middle name—just Gregory. Greg, to his friends. Now, as he passes his 50th birthday, Gregory is ready to make a change, by legally adopting a second, or maybe a first, name.

But, he says, no more than two.

Although he traveled extensively with his father when he was in his teens and twenties, large enough to be mistaken for his father’s bodyguard at the time, Gregory has lived mostly off-the-grid for the past several decades, working as a long- and short-haul trucker, moving from state to state, and keeping his wins and losses in his battles with addiction a safe distance from his family. Now, as his father, 84, travels the country in support of the John Legend-produced play based on his life, a nationwide stand-up comedy tour, and his civil rights activism, Gregory has moved back to Washington, D.C., to be closer to home base of the man who was, by his own admission, absent in raising his 10 children, to help with the logistics and the tours and the promotion, to be there, when needed, to aid in the Herculean task of managing Dick Gregory, the man and the brand.

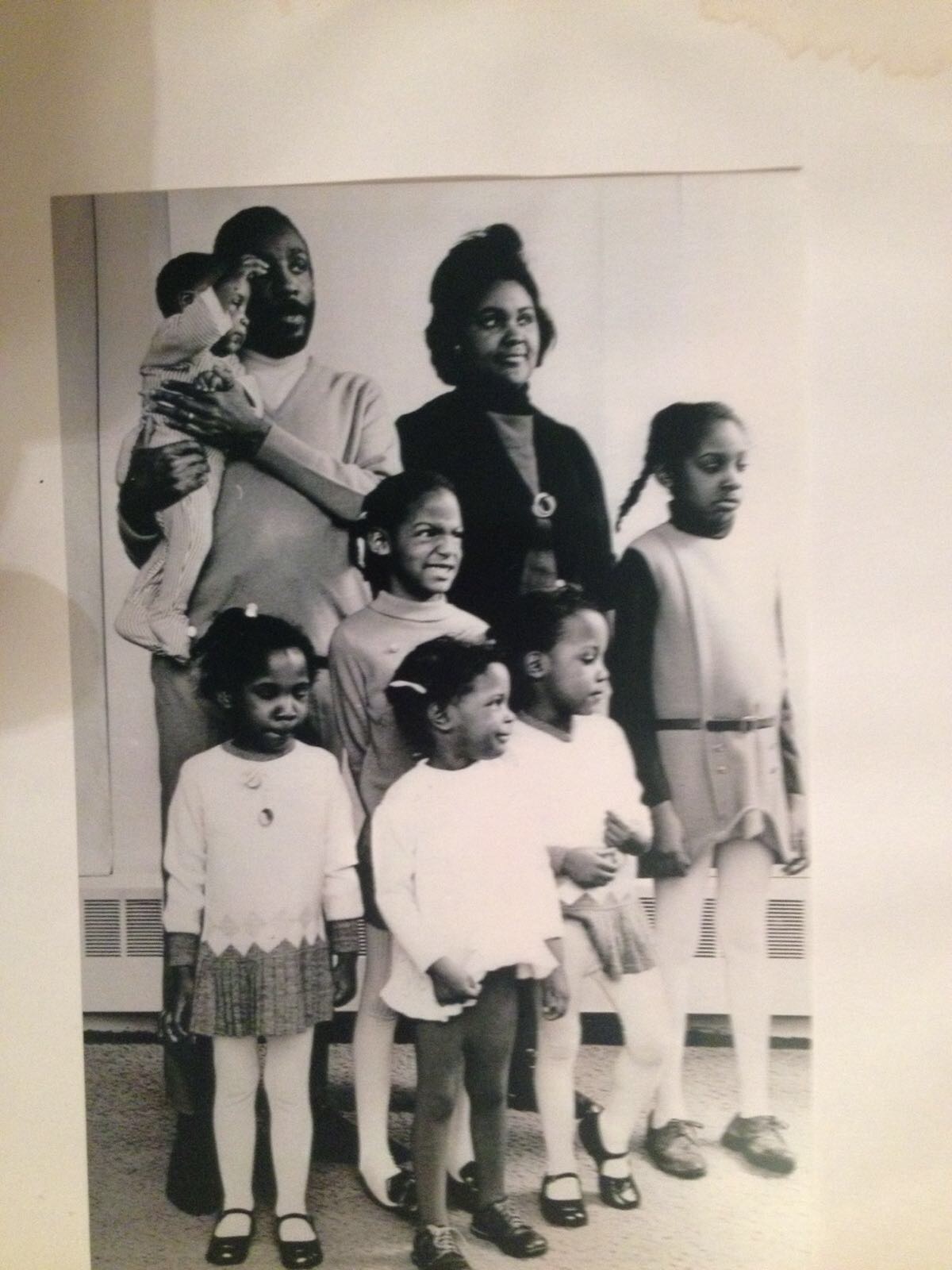

(Photo: Courtesy of the Gregory Family)

And Gregory is there; the two now live in the same apartment building in the historic Shaw neighborhood, and although Dick has his own place, he’s over at Gregory’s so much when he’s not traveling that the two are, essentially, roommates. Until Gregory legally changes his name, though, there’s a limit to how much support he can provide his father.

There are some benefits to being mononymous. The draft board never did find him, for instance, although it attempted to once by sending a draft notice to his sister with a request that she help them. (She didn’t.) And during a youth that contained more than a few scrapes with the law, the inconsistency with which law enforcement officials entered his name into their system—from Mister Gregory to Gregory Junior to Comma Gregory (yes, they spelled out Comma) meant that Gregory’s record was, as his younger brother Christian put it, “Three times worse than anyone knew.” That trend held throughout his life; when he went to pay a recent speeding ticket in Mississippi, Gregory discovered it had been dismissed because the officer had entered it incorrectly into the system.

But, of course, there were drawbacks as well. Routine navigation through bureaucracies, which can stymie and frustrate the polynymous on their best days—obtaining a driver’s license, filling out a rental agreement, completing banking forms, having cable installed, calling and updating the credit card companies on a new address—quickly become Sisyphean tasks for someone with only one legal name.

But those tasks are just minor nuisances when compared with the biggest hurdle: In a post-9/11 world, Gregory cannot get past the Transportation Security Administration, and so, he cannot fly.

Gregory is hardly the only child in the esteemed clan with a politically driven name. Dick and his wife Lillian (Lil) frequently toyed with convention when naming their children, and as those children grew, some changed their own names. Gregory’s nine brothers and sisters include Michele; Lynne; twins Pamela Inte and Paula Gration (so the twins would be inte-gration, get it?); Stephanie, who now goes by Xenobia; Christian, a physician who runs a private practice in D.C. and also serves as his father’s business manager; Miss, who was named so that even the most racist would have to address her as Miss Gregory; singer Ayanna; and Yohance, or Yoey, as his brothers refer to him, who changed his last name legally from Gregory to Maqubela in honor of a professor he once had and to connect with his African roots.

When I ask Gregory the first time he fully realized how having one name set him apart from his peers, and even his siblings, he seems stunned. “To be honest, until you asked me that, I never really even thought about it,” he says.

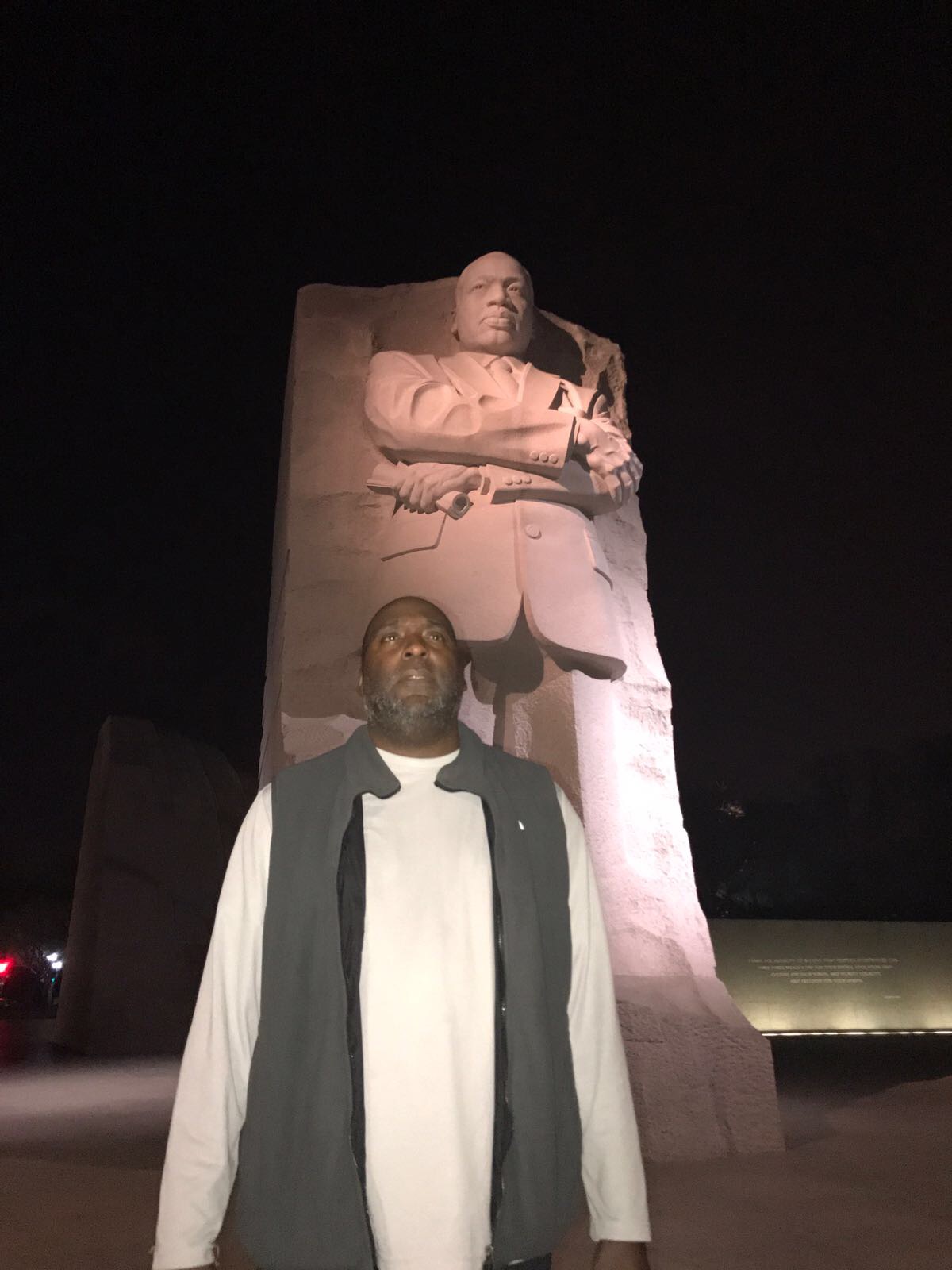

(Photo: Molly McCluskey)

It’s early Sunday morning, and we’re sitting in the common room of the upmarket building where Christian lives, also in Shaw. Gregory moved to D.C. from Mississippi the day before and, in two hours, Christian will interrupt us to remind Gregory they need to return the rental truck. He’d unloaded the last few items into his apartment before coming to meet me, and he’s still dressed in dark athletic wear, drinking a Frappuccino from a glass bottle.

Gregory’s nervous at first; he’s not the one in the family who usually gives interviews. That’s Dick, or Christian working with the media on their father’s behalf, or Ayanna, for her music. He isn’t sure why I wanted to speak with him; he doesn’t think his story is unusual. But Christian has been my chiropractor for a few years now, and when he mentioned he was helping his brother Gregory move to town, not Gregory Gregory, which would have seemed odd enough, but just Gregory, I had some questions.

Unlike the routes Greg has driven for years as a long-haul trucker, our conversation is a journey without a map, and we often arrive at unintended destinations; we would start talking about the logistics of financial management and end up at a conference in the 1970s in Los Angeles that was run by John Denver in which Dick said the moon landing was a hoax with a member of NASA in attendance. He doesn’t mention the time that Dick landed in a helicopter on the football field of his middle school, sauntering across the end zone with Hustler‘s Larry Flynt when Gregory got in trouble for drinking a beer on school grounds—that story comes from Christian a bit later—but Gregory does remember the time that, as a child, he walked in on Farrah Fawcett and Ryan O’Neal in bed in a hotel room, or how the parade of celebrities through his hometown of Plymouth, Massachusetts—famous for a rock, pilgrims, and the first Thanksgiving—affected their neighbors, and their local standing. And he recalls vividly the time a rural, white farmer approached his dad to say he had seen a video of him performing at the Playboy mansion. Which is to say, our interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start from the beginning. What is your name?

My only birth name, never been changed, is Gregory.

Gregory. And how did that come about that you only have one name?

I’m the oldest boy out of 10; there are five girls older than me but I am the oldest boy and Christian, and then Yoey. My dad being Dick Gregory, back in 1967, when I was born, said his oldest boy will never have to register for the draft. He said, “If I only give him one name, the Army computers won’t even be able to set it up.” So that was the logic behind the one name, and it’s been an experience to say the least.

And so were you registered for the draft?

No. They sent something to a sister under me, but no, I never registered.

(Photo: Courtesy of the Gregory Family)

Not only were you not registered for the draft but it sounds like there have been a wide range of government and local things that you could not register for.

Without a doubt. That’s something that I thought later on in life. As a kid, I didn’t know. On the first day of school, the teacher always read the names, and it got to me. “Ah, Gregory…” you know, as me and all my classmates came up in years, the first days, they couldn’t wait to tell the teacher, “Oh, he’s only got one name!”

Or sometimes, I would go up to the teacher if there were some new faces, or I felt uncomfortable, with peer pressure or whatever, and I would tell (the teacher), “Look, when you see one name on there, that’s correct, I only have one name.” And, sure enough, the birth certificate, where it says first is blank, middle blank, and then it’s got the Gregory for the last.

When did you first notice, or when did it first really dawn on you, that having one name was a different experience? Was it the first day of school, was it being around your siblings who have two names?

Obviously the schooling things, but that was more like, I didn’t want nothing to do with it. Wow, I never really even thought about that. I would say probably like going to get my license, you know when I was a teen and older, when it was … a lot of people would say, “You’re like Prince or Madonna,” but, you know, that’s their stage name. My only name is just Gregory.

Was there ever a moment when you were a kid and went home and said, “Mom and Dad, why do I only have one name?” I mean, because the Vietnam reason is clearly a piece of the family legacy of why you only have one name, but when did you have that conversation with your parents?

To be honest with you, I don’t recall, and, in my mind, I don’t think we ever even had that conversation.

(Photo: Valerie Macon/AFP/Getty Images)

Did you ever feel like being Gregory was more an individual thing for you, like, Wow, I’m the only one in my family with one name, or was it more that you were wrapped up in the family so closely that you didn’t have your own individual identity?

A little bit of both, to be honest with you. Obviously being the oldest boy and with dad always being gone, with five little sisters, on Saturdays, I don’t need to tell you, what couldn’t be said to dad, could be said to me, and you can believe that. I mean, I love them to death, and yeah, I would say a little of both. Obviously we had our fallings out as kids, but overall, yeah, I would say a little bit of both on that question.

And obviously, the identity of having a famous father, and being the eldest son of a famous father, must have also had its own connection to the name.

In ’72, we moved from Chicago, to Plymouth, Massachusetts, and we went from seeing a lot of people like this (points to his skin color) to being the only one, and I’m telling you, I maybe was called the n-word one time. And it was that, the fact that we didn’t eat meat, and looking like we did—

You stood out a little bit.

I remember one time one of the television reporters from Boston came out to interview my dad, and then the kids started to realize, Oh, the Gregorys, their dad is famous. And it made things easier for us than they might have been. Our skin tone, and just, it was … wow. It’s funny how you asking me that made me think about that a lot.

Asking you when you first knew it was a different thing?

Yeah, and the whole thing with dad’s celebrity status and everything.

Did you ever just decide at any point that you were going to start calling yourself another name, to take your own identity, and claim something out of the ether for yourself?

(Photo: Courtesy of the Gregory Family)

Yeah. The thought went through my head. And it was never like if I did it, dad would have a problem. And you know, really, that question you just asked me, I can’t recall, as a kid, being that distraught about it, even though, as I said, there was the peer pressure thing (on the first day of school), and that was really the only issue.

Well, it marked you as different from the outset, that very first second of every year, you were the different kid, in a number of ways, it sounds like.

Exactly.

I mean, you couldn’t even have that brief moment of being the same.

You know how they say things that are painful for you, you push as deep down as you can? I don’t know; I might have to see somebody.

You have a son.

Yes.

Is he your only child?

Yep.

May I ask if you were married to—

No.

So you didn’t have to deal with getting a marriage license with one name?

How about that? I never even thought about it.

What is your son’s name?

Hodori Courtland Gregory. Hodori is Swahili. It means strong. Courtland is my maternal grandfather’s name. And I’m a grandfather. He’s got two beautiful children.

Wow, congratulations. And were there any conversations with your son as he was growing up about why dad only has one name?

No. I just assumed that everybody who knew of the family and me knew, and some really didn’t know that it was a legal thing. I would show them the driver’s license, and say, “Look, this is really a thing,” and they’d say, “Oh we thought we were just calling you Gregory.”

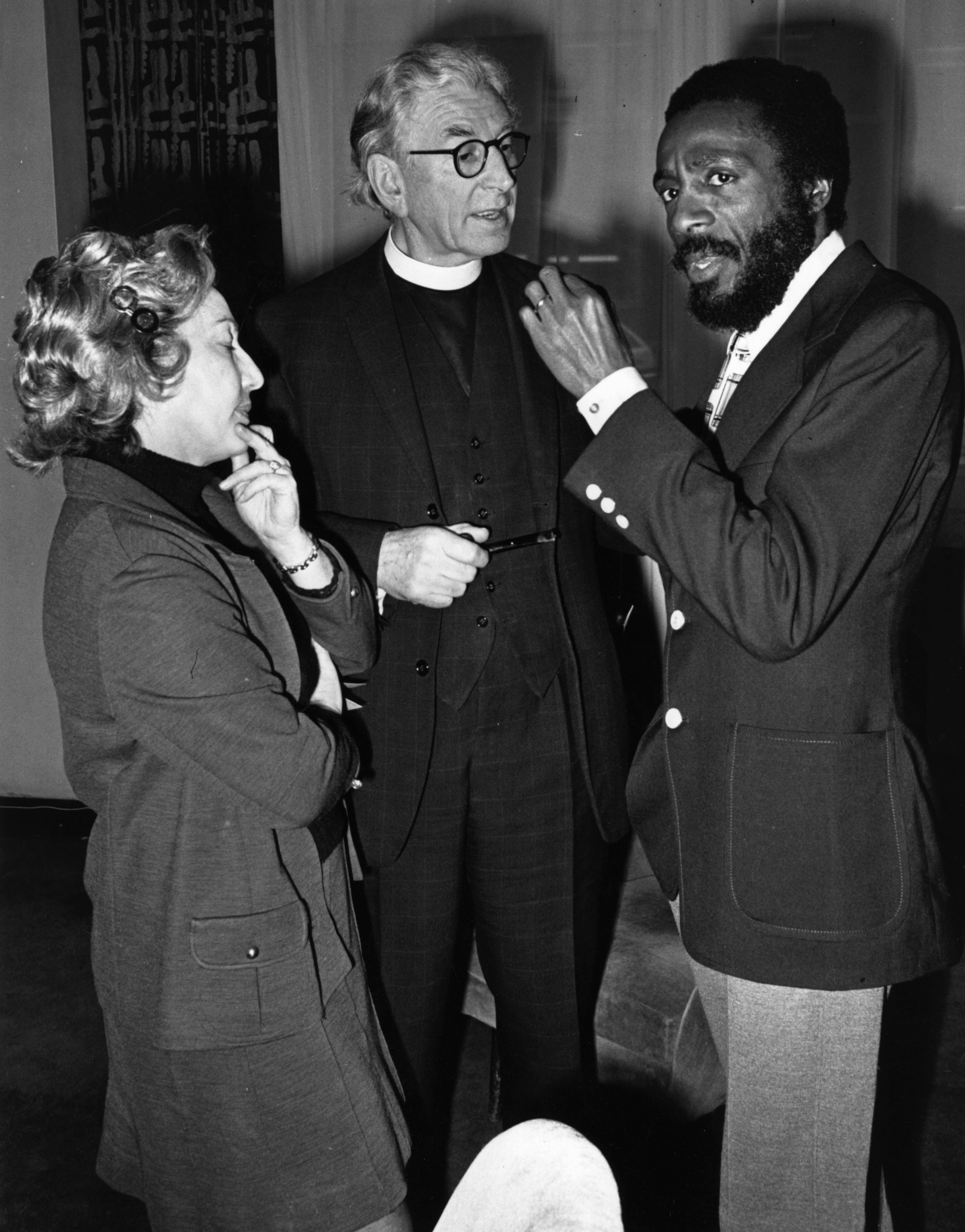

(Photo: Three Lions/Getty Images)

I mean, my satellite service back in Mississippi, setting that up. You know, over the phone, I can tell them ahead of time, and say, “Look, I’m not trying to be rude or anything but I legally only have one name.” Molly, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve done this scenario. And after going through all of that and saying, on my social security, birth certificate, blah blah blah, they’ll still say, “OK, and your last name?” I get upset but I have to realize that this is extremely rare. Because it’s like, you know, it’s just like ingrained in this society we have two names.

Christian mentioned that, when you were a kid, one of the benefits, if it were, of having the one name, was that when you would run into little scrapes with the law, they wouldn’t know how to put you into the system, so that sometimes it was one way, and sometimes it was another way, and he joked that you were actually three times as bad a kid as everybody thought you were. What were some of the things that you were running into?

Well, it’s like that speeding ticket in Mississippi. I went to pay it and the clerk couldn’t find it in the system, and then when she did finally find it, it wasn’t entered properly, so she said it would be dismissed. I kept asking, “Are you sure?” And she said it was fine. It was like that when I was a kid. I mean, they put Gregory, they put Greg Gregory, Unknown Gregory, Gregory Doe, yeah, Comma. I used to live in Michigan. Like Christian said, my ID now, you know, some agencies, like Michigan, they said that something has to be in this box, with the new computer stuff there’s ways around it, I mean with other licenses I’ve had, yeah, they put Comma Gregory. That was classic.

Part of me wanted me to say it the right way, but another part of me thought: Just stay quiet. Just be quiet. So I’m making sure that nothing can come back later on.

I keep thinking of the logistics of this for you. The logistics of things like getting a job, and getting paid and getting that paycheck into your bank account. Even getting your name changed sounds like it’s going to be an intensive process.

I’d have to get a court order to get my raised seal birth certificate, which I’m going to need, you know, I have a copy, but, as you know, the real legal stuff, or name change or IDs, they want to see that original birth certificate. I lost it some years ago. I called and they told me I had to call Springfield, and the lady there said a law was passed just within the past year, where they can’t release ones with just one name, she said what you’re going to have to do is get a court order to get your birth certificate.

(Photo: Courtesy of the Gregory Family)

And you’re a long-haul trucker now, right? How long have you been in that job?

I’ve been driving going on 20 years. The truck driving, I got into that because I liked driving and I always liked construction type of things. I felt more comfortable, you know, being up high and all that, but it was just something I got into on a whim.

Same company?

No. Different. I haven’t even been in long haul for maybe 10 years; I’ve just been on local routes.

So how, when you have an employer—

They put Greg Gregory. A lot of them do. So that’s going to be my official name.

When did you really decide to make a commitment to traveling with your father, and learn about his work, and take some of it on yourself?

When school was in session, it was the boots and jeans and flannel shirt Greg, and in the summer, I was traveling with him. I mean, when I went to Atlanta, to go to Morehouse College, it was like a culture shock, because I had never been around that many black people, that were like Steve Urkel type. It’s like how caught up I got, in being with my dad and being Dick Gregory’s son and the celebrity status I had with that. I got caught up in all the attention and everything that was thrown at us, and never thought, Wait a minute, they’re not supposed to be treating black people like this.

You were a celebrity.

(Photo: Keystone/Getty Images)

I accepted that. And not that that was a problem. If anything that would have been even more easier to be in that world, being Dick Gregory’s son at Morehouse, and it’s where Dr. Luther King went to school, and, hell, Bill Cosby’s son was there. You know, guys better than me, good-looking guys that girls wanted more than me probably and you know a lot of that was a culture shock. But coming up the way I did, the eldest son, and the one name, and suddenly I’m in a new environment, and my ego caught up with me a bit.

When you left Morehouse, you began traveling with your dad full-time.

I did two years there and then really started working with him on different projects. I really liked that, and we had a lot of good projects.

When I was at Morehouse, I saw my dad more in Atlanta than I did at home, because, you know, he was in Los Angeles in the morning, New York maybe in the afternoon for a thing. Me and him, like they said, they said, “Gregory, we thought you were going to be the one to follow and do something like that.” It’s not too late, I guess. We shall see.

Do you ever recall there being issues with the name or ticketing then?

I’m sure it was Greg Gregory. Pre-9/11 TSA, you could just take your ticket out and your license. There was rarely, they would look at it and see the one name, or on the ticket, we’d put Mr. Gregory, or Greg Gregory, and they’d look at your ID, and you’d go on. But I remember hearing somewhere that it’s common in some Muslim countries for men to have one name, and I wonder if that’s part of the issue now.

After 9/11 how has that changed for you?

When my niece passed away last year, I had to drive from Mississippi. When the funeral was being planned, Christian literally went to the TSA headquarters in D.C., and told them the whole story, and they said there’s nothing you can do, he’s going to have to change his name. Because, as they said, get your license, get your ticket out. What’s on that license better be on the ticket and vice versa. The airlines can’t print the ticket with just one name. All the other years, it was Mr. Gregory or Greg Gregory, and there’s nobody standing at the gate, checking that the name matches the ticket exactly. Yes, that’s now my only option, to change my name.

(Photo: Courtesy of the Gregory Family)

I mean, I’m 50 years old, so it’s not like—

The Vietnam War is over.

Yeah.

So what is the point? I mean, you’re 50, why now?

Really for the travel thing, to be able to assist dad.

So what are you looking forward to the most after this whole crazy drawn out process of paperwork and bureaucracy and dealing with government officials, which I don’t even like to do when I have to update or renew my driver’s license?

I guess just getting things done quicker maybe.

Are you going to hop on a flight and just fly through TSA and—

Exactly. I might go around showing my license now. I’m just kidding. But something like a family emergency could come up, and it could be something that driving wouldn’t be possible because of the time.

Do you think it will change anything for you?

I think people will know me as, Oh, that’s Gregory.

But what about you? Your sense of your name and identity.

I really don’t think it will change anything, because, deep down inside, that was always my alias, so to speak. It was Greg, or Gregory Gregory Gregory, as the kids wanted to give me a first, middle, and last name. We can probably count the people—family and some—who really know that that’s really my only name, who have always just assumed, they call him Gregory.

So it’s legally going to be Greg. Are you doing a middle name? I mean, why not go all out?

I thought going African, then I thought, Let’s just keep it simple.