During the height of the Soberanes Fire last September in Central California, the United States Forest Service estimated it was costing about $8 million per day to fight the wildfire. By the time firefighters fully contained the blaze at 132,000 acres, it had become the most expensive wildfire in U.S. history, with a total cost of more than $206 million.

The Soberanes Fire wasn’t even one of the 10 largest on record in California, but the high price tag is one of the signs that the U.S. is losing the battle against wildfires. Moreover, according to a new study based on research in Colorado and California, the Forest Service and other agencies simply won’t be able to keep up with bigger and longer-lasting fires unless they adopt a new, forward-looking attitude and different strategies to prepare for wildfires in the era of global warming.

The researchers behind the new study, published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that, instead of trying to fight every fire or thin vast areas in futile prevention efforts, the Forest Service should focus on protecting communities and limiting new development in fire-prone areas, while letting some fires — even large — burn, which will help Western landscapes adapt to climate change in the decades ahead.

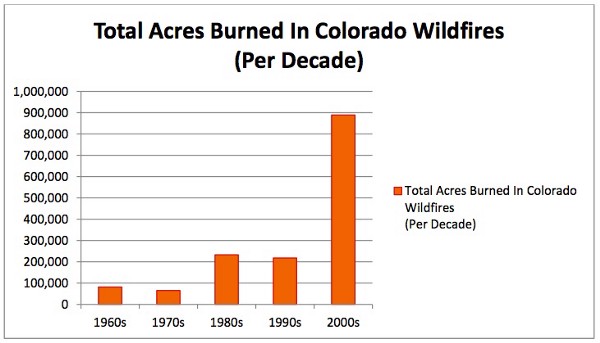

(Chart: U.S. Forest Service)

“We will never be able to control wildfire,” says co-author Tania Schoennagel, a research scientist at the Institute for Alpine and Arctic Research at the University of Colorado–Boulder. “We have to learn to live with it and adapt, just like we do with droughts and flooding. Our current wildfire policies can’t protect people and homes,” she says, adding that many have underestimated the extent of climate shift in the American West, which is warming nearly twice as fast as the global average.

“In our paper, we speak to a pretty uncomfortable idea that we’re going to have to accept this change,” Schoennagel says. “It’s kind of folly to replant large areas that are not regenerating. It’s getting warmer and drier at the southern edges of species ranges. Climate change is going to have a fundamental and lasting effect across large landscapes. This administration may not recognize the human causes of climate change, but it will have to deal with the consequences.”

Nine of the 10 biggest fires since 1960 have all been since 2000. In the cool and wet forests of the Pacific Northwest, large fires have increased by 1,000 percent; in the Northern Rockies by 889 percent, and by 462 percent in the Southwest, according to data Schoennagel compiled as part of the study.

“This administration may not recognize the human causes of climate change, but they will have to deal with the consequences.”

The cost of fighting fires has also spiraled out of control recently. In 2015, the Forest Service spent more than half its annual budget on trying to put fires out. Since 1970, the average temperature in the West is up two degrees Celsius, and the fire season has lengthened by 78 days. At the same time, the population in fire-prone areas increased sharply—all the ingredients for a disaster unless we drastically change the recipe, according to Max Moritz, who co-authored the paper.

“Climate change is pushing us in this direction where we’re going to have to do things really differently. But, sadly, we’re probably going to have some big losses of lives and property that will catalyze action, making people realize that we’re living in a way that’s out of balance with the climate and the environment,” Moritz says, just before heading to a meeting about a community wildfire protection plan in Santa Barbara, California, where he’ll try to use some of the insights from the research to shape policies that will enable communities and ecosystems to adapt.

“Some Familiar Landscapes Will Disappear”

There was strong new evidence for the long-suspected link between global warming and wildfires in a 2016 study, making it all the more urgent to start thinking differently about wildfires, which isn’t all that easy because of prevailing cultural attitudes and values.

(Photo: National Park Service)

“Part of the challenge is that we’re caught in a very specific mindset about how we view fire. We think of fighting fire. That’s the kneejerk common reaction that’s almost universal. We’re going to be reactive … the entire approach is like Band-Aids, and it’s getting super expensive and ineffective,” he says. Instead, people have to accept that some familiar landscapes will disappear.

“We’re not willing to talk in the context of giving up landscapes that we value. Under climate change projections, many ecosystems and species are not going to persist where they are right now, but we have a choice. We can actively help those landscapes be prepared for conditions that may exist in the future by using fire,” he says. “We need the foresight to help guide these ecosystems in a healthy direction now so they can adjust in pace with our changing climate. That means embracing some changes while we have a window to do so.”

Specifically, the adaptive, resilient approach outlined in the study says fuels reduction (thinning trees, removing brush) won’t change regional wildfires trends. Instead, land managers must let more wildfires burn and use more intentional fires to help forests, brush- and grasslands adapt to a changing climate. There also must be more effort on incentivizing and planning residential development to withstand inevitable wildfires.

Why Thinning Won’t Work

America has spent about $3 billion on cutting crowded trees and clearing brush on 17 million acres of forest since 2001. During that same span, wildfires continue to rise, and there’s no proof that thinning is working. Schoennagel says most of the thinning has been on federal lands, but the dangerous fires are on private lands.

“I wondered for years why a different PR message is not going out. We cannot change this equation through thinning,” Schoennagel says.

“We need to shift our view and keep in mind what the future variabilities might be, and how we can manage for that,” Schoennagel says. That requires perceiving landscapes and ecosystems in a new way. For example, long-lived forests in mountain areas established themselves when climate conditions were suitable. In the climate-changed future, those conditions will no longer exist. “We should allow those areas to burn and adapt for future conditions. I think we see fire as a consequence, but it can also be a tool to help us keep pace with climate change,” she says.

Can Fire Fight Fire?

That includes intentionally set fires, but there are significant obstacles to carrying out such prescribed burns. The biggest is the potential legal liability for fires that escape and cause damage, and there are also aesthetic and health issues related to the smoke from such fires. Schoennagel says since those impacts will happen sooner or later, it’s better to do it now, in controllable increments.

On the community side of the wildfire equation, the single biggest challenge is that current policies favor continued building and development in fire-prone areas, which is putting more and more people and properties at risk.

“There are few policies that are really forcing change on this front,” she says. With federal agencies picking up most of the cost and risk for fires, there’s little motivation for development limits. Shifting at least some of that cost toward counties would offer a “striking” incentive to reduce building in the fire-prone red zone.

“They (counties) get lots of tax revenue from that development. What’s the point of restricting it if you know the feds are going to pick up the tab?” she says. “The equations need to be set differently so that the costs and risks are borne equitably.”

Other options include efforts like those in Boulder County, Colorado, where an expert wildfire board helps property owners audit their homes for wildfire risks. If those risks are minimized, they can get lower insurance premiums, she says. In Summit County, Colorado, residents taxed themselves to create a wildfire safety program that also includes audits and even direct subsidies to reduce wildfire risks in communities.