What if the Food and Drug Administration decided to regulate your Fitbit? Imagine if the agency declared that dozens of popular consumer devices — Fitbits, Jawbones, Garmins, Misfits, and the like — met the regulatory definition of a medical device, and couldn’t be sold until the FDA certified that they reached the standards required of clinical-grade technology. While it’s true that fitness-tracker data is not always especially accurate, we don’t need the devices to meet the clinical standards required of a diabetic’s blood-sugar meter or a pacemaker. Even if the numbers aren’t perfect, many of us find the data useful — and even fun — for learning more about ourselves and our health habits. We don’t need the FDA to protect us from that.

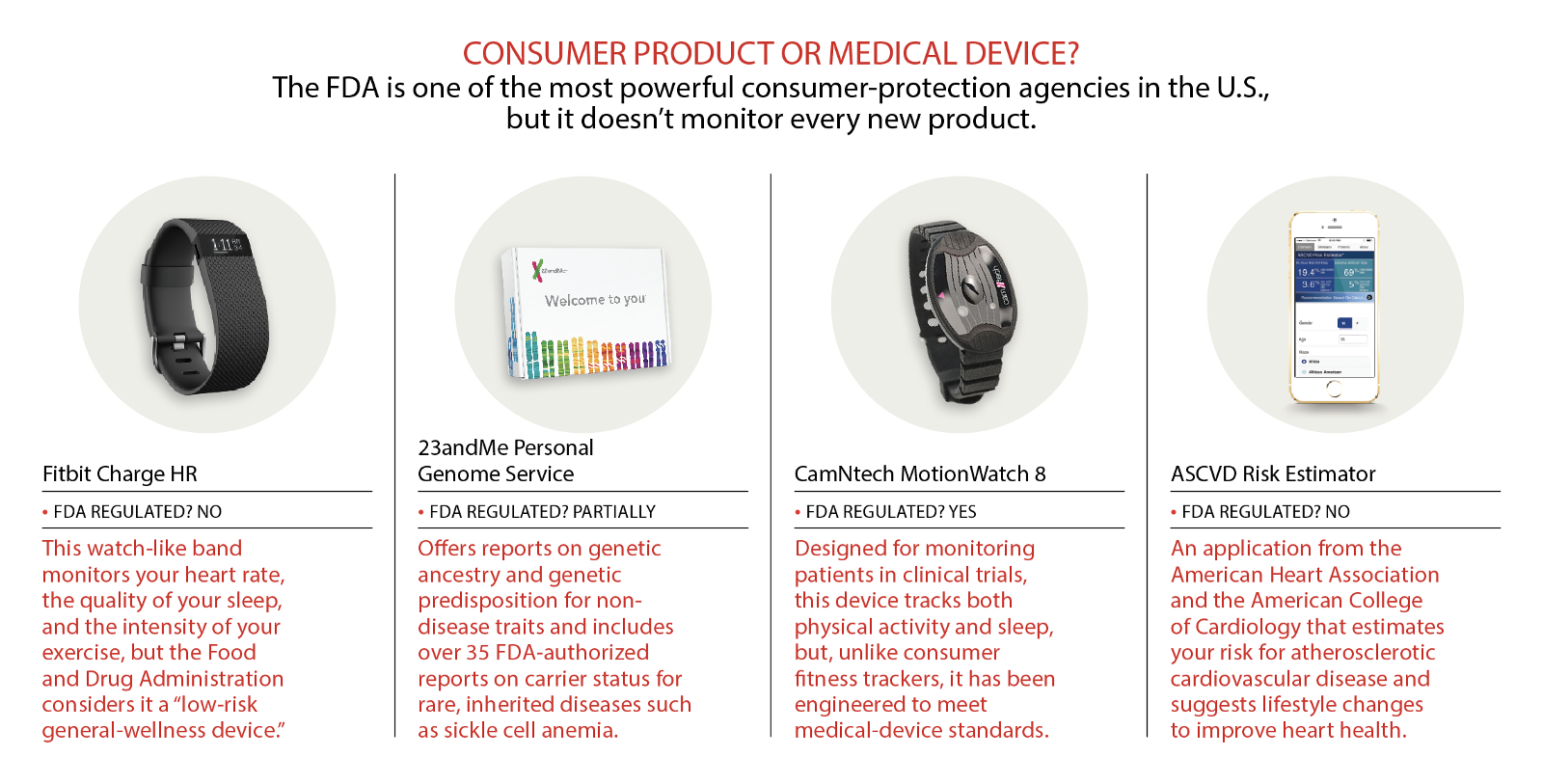

Thankfully, the FDA hasn’t classified fitness trackers as medical devices. But the agency has over-regulated a different health technology: direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic tests. Like fitness trackers, DTC genetic tests, such as those sold by 23andMe, offer us non-clinical-grade data about ourselves, data that satisfies our curiosity and can inform our lifestyle choices. Also like fitness trackers, DTC tests pose little risk of harm, and thus should not be regulated at the stifling standard of “medical device.” Instead, they should be handled like other low-risk consumer health products: Regulators ought to keep DTC testing companies honest in their claims, but also recognize that genetic information is interesting and useful to many people, even if it isn’t rigorous enough for a medical diagnosis.

Modern DTC genetic tests became widely available in 2007, thanks to advances in low-cost DNA analysis technology. Taking a DTC test is simple: You order a sample-collection kit from the company, spit in a tube or swab your cheek, and mail it back. A month or two later, you read an analysis of your DNA online, which, depending on the test you take, might include information about your ancestry and your possible genetic predispositions for a range of health-related traits. By late 2013, a leading company in the industry, Google-backed 23andMe, claimed to have sold its genetic test to over half a million customers, under the slogan “Living well starts with knowing your DNA.” For $99 (just about the price of a Fitbit Flex), 23andMe users received risk estimates for over 250 different traits and diseases, ranging from relatively benign ones like lactose intolerance to serious diseases like cancer.

But in November of 2013, the FDA ordered the company to stop making risk assessments, citing concerns that customers would disregard or bypass their doctors and make bad health decisions based on an inaccurate test. The FDA declared that it considered 23andMe’s test a medical device that could have “significant unreasonable risk of illness, injury, or death,” and was therefore subject to regulation. As a medical device, 23andMe could not sell its test until the FDA approved it, which the agency would not do until the company proved the clinical validity and accuracy of its claims.

Critics complained that, by treating 23andMe’s DTC test as a medical device, instead of as a non-clinical consumer product, the FDA was unjustly locking up personal information that people had every right to know and handing the keys to medical gatekeepers. “Is the FDA going to issue Fitbit a cease and desist letter too?” asked Duke University bioethicist Nita Farahany, who argued that it’s absurd to consider something a medical device merely because it provides information that might be relevant to a person’s medical care. Writing in The New Yorker, science journalist David Dobbs argued that, by shutting down DTC tests, the FDA was leaving genetics “in the hands of a medical establishment” that has failed to let people “obtain and use the elemental information in their own spit.”

Critics also argued that the FDA’s logic for regulating DTC tests is built on a flawed premise: Multiple studies, comprising thousands of subjects, had found no evidence that DTC genetic tests caused distress or misunderstanding that resulted in dangerous health decisions. Farahany, together with Robert Green, who directed a National Institutes of Health-sponsored study to understand how DTC users handle their genetic information, noted that the results of these studies “suggest that consumer genomics does not provoke distress or inappropriate treatment.” FDA policy, however, didn’t budge. Answering critics, Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, insisted that, while some genetic information can be fun, “Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and heart disease are serious matters.” Therefore, genetic tests for such diseases must meet high standards for accuracy.

But even those opposed to the FDA’s action recognized that the government wasn’t entirely to blame. The agency has a mandate to protect the public from fraudulent or misleading health products, and, for years, it had engaged with 23andMe to discuss what level of regulation would be appropriate. In the summer of 2013, however, for unknown reasons, the company stopped responding to the FDA. At the same time, 23andMe was advertising increasingly bold claims about its product’s health value. On its website, it said the test would help customers “take steps toward mitigating serious diseases” and allow them to “find out if your children are at risk for inherited conditions” — even though, in the fine print, 23andMe noted that its test was “not intended to be used … for any diagnostic purpose.” 23andMe’s advertising claims had become a source of controversy among scientists and policy experts, who recognized that the inexpensive technology used by the company and the current state of scientific knowledge were too limited for DTC tests to be of much value in serious health decisions. Writing in The New England Journal of Medicine, health policy experts George Annas and Sherman Elias argued that the FDA’s ban “is not currently depriving people of useful information.”

Furthermore, the ban did not resolve the core tension that has dogged this field from the beginning: People have the right to learn what science has to say about their own DNA, but companies need to be honest about the limited medical value of DTC tests. Michael Eisen, a geneticist at the University of California–Berkeley and a member of 23andMe’s scientific advisory board, argued that DTC tests should be regulated “fairly tightly,” but, at the same time, the government should acknowledge that people have a strong right to obtain the latest scientific information about their DNA — even when the meaning of that information is still unclear.

“The challenge,” Eisen wrote, “is to come up with a regulatory framework that recognizes the fact that this information is — at least for now — intrinsically fuzzy.” For example, in 2013 23andMe’s test included 11 genetic variants associated with Type 2 diabetes. The company provided users with a summary of the science and cited the relevant studies, but those 11 genetic variants by themselves are not nearly enough to reliably determine whether someone has a higher genetic risk for diabetes. The big problem is a false negative: Geneticists know that many more variants contribute to the disease, but these remain largely undiscovered — and thus can’t be included in 23andMe’s test. Test users should be able to learn whether or not they carry known diabetes variants, but they also need to be clearly informed about the level of risk associated with a positive result — and why a negative result doesn’t mean they’re 100 percent in the clear either. The FDA’s job should be to keep 23andMe honest about the uncertainties, not to impose impossibly high standards for accuracy.

Unfortunately, that’s not the approach the FDA has taken. In the fall of 2015, 23andMe again began selling its health test, with new, FDA-approved genetic reports. (The company had continued to sell its ancestry test, which was not regulated by the FDA.) But the new health test is now a stripped-down version of its former self, and costs the consumer twice as much as it did before. Instead of reports on over 170 diseases and health-related traits, the test now reports on about 50. The only disease information is presented in roughly 40 “carrier reports,” which determine whether you carry a mutation for a rare, inherited disease like cystic fibrosis, which you might pass on to your children. 23andMe removed over 100 different diseases and conditions from the new version, including Type 2 diabetes. These are conditions for which scientific knowledge is still, in Eisen’s words, “intrinsically fuzzy,” but they are also the ones that most of us are interested in: breast and colon cancer, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s, to name a few. The FDA still considers 23andMe’s DTC genetic test a medical device, which means that fuzzy information is not allowed — even if it comes with appropriate cautions and a clear explanation of how confident users should be in their results.

If DTC genetic tests shouldn’t be regulated as medical devices, what’s the alternative? A better approach would start by treating these tests more like other consumer-wellness products — such as Fitbits. Like fitness trackers, people buy DTC tests for a variety of reasons, most of which have little to do with making serious medical decisions. Test takers are motivated by a desire to take part in research, to share and discuss their results with others, and to sate curiosity about themselves. Barbara Prainsack, a sociologist at King’s College London, and her colleague Mauro Turrini, at the University of Paris, point to surveys that show “what users ‘get out of’ DTC genetic testing has little, [if] anything, to do with clinical decision-making.” The FDA, and the medical community more generally, need to consider the uses of genetic data more broadly. “Genomic information,” Prainsack and Turrini argue, “is personal and social at the same time.”

As it turns out, the FDA recently developed guidelines for how it will deal with fitness trackers and the rapidly growing number of mobile applications devoted to health. Rather than treat apps and fitness trackers as medical devices, the FDA has decided to approach these mostly non-clinical technologies from a consumer-protection angle. It has partnered with the Federal Trade Commission, the government’s other major consumer-protection agency, and the Office for Civil Rights to focus on protecting the privacy of users’ data and ensuring that companies don’t make misleading claims about diseases.

With some modifications, the FDA could apply this regulatory framework to DTC tests. As long as companies tempered their claims about predicting your genetic risk for disease, or received FDA approval for stronger claims when the science is good enough, they could help us learn what one of the most exciting fields in modern science has to say about one of the most uniquely personal parts of our biology. The cutting edge will always contain uncertainties, but the solution should be to explain those uncertainties, rather than hide them.