Nearly a quarter of Austria’s total farmland comprises seasonal mountain pastures—land that now finds itself threatened by climate change.

By Bob Berwyn

Cows graze at an Alm near the Grossglockner, Austria’s highest peak. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

Upon our arrival at the Almhaus Hochbärneck in June, the innkeeper handed us the keys to the farmhouse and guided us to the stash of snacks and apple cider. She told us she’d be back the next morning to fix breakfast; in the meantime, we settled into our simple room and opened the window to the sound of a hundred cowbells ringing a mountain lullaby. Baritone bells clanged nearby, alternating with a more distant tintinnabulum, giving audible form to the Austrian mountain pastures around us.

Similar scenes are repeated thousands of times in this alpine nation and across the European Alps: tens of thousands of cows, goats, and sheep spend summers grazing on seasonal mountain pastures. In Austria, these carefully tended patches of mountain land are called Alms, but transhumance pastoralism spans nearly all mountains on every continent, from llama-herding on the Puna grasslands of the Andes, to the yak feeding on Asia’s high steppes and among the crags of the southern Saharan mountains, where rock etchings suggest cattle grazing during the last Ice Age.

In the Alps, seasonal mountain grazing has gone unchanged since the High Middle Ages, historians say. That the practice has carried on serves as a link back to the semi-nomadic cultures that marked an important early evolutionary milestone on humanity’s path from hunter-gatherer to agrarian, as we learned to sustain ourselves for longer in one place by harmonizing with seasonal cycles and local environments.

There’s evidence that some of the sure-footed cows grazing today are descendants of cattle that first crossed the Alps from the south with Neolithic migrants colonizing new high ground after the last Ice Age. Mountain agricultural communities in the Alps were redoubts of civilization in the aftermath of the Black Death.

Mountain clearings in the Austrian Alps are carefully maintained as summer pastures for cattle that is seasonally herded up to higher elevation meadows. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

Official documents in Austria designating summer pastures date back as far as 1204, and, these days, there are more than 10,000 Alms scattered across the country, with 60,000 farmers tending about 500,000 cattle. Nearly a quarter of Austria’s total farmland is comprised of seasonal mountain pastures.

About 15 percent of the country’s cows (along with smaller herds of goats and sheep) are grazed on the Alms, a fact that reduces the greenhouse gas emissions considerably, according to the European Joint Research Centre. Across Europe, producing a kilo of beef generally creates 22 kilograms of CO2; in Austria, that figure is 14.2 kilograms, by far the lowest value in the European Union. And with agriculture accounting for about one-third of all global greenhouse gas emissions, that’s an important disparity.

Austria’s pastures have been grazed so long that they’re woven into the cultural and natural fabric of the region. The grazed clearings are scientifically recognized as important ecological hotspots, part of a patchwork landscape pattern that fosters species diversity — and also stores carbon.

A recent study in the German Alps shows that organic forest topsoils have lost 14 percent of their carbon since the 1980s, but in nearby grazed pastures, the level has stayed about the same. The warming is speeding up microbial activity in the forest soils, which breaks down the organic carbon and releases it to the atmosphere, says researcher Jörg Prietzel, who published his findings in Nature Geoscience.

Grazed in careful rotation, the pastures foster wildflower growth and habitat for pollinators, which, in turn, provide food for birds. Alternating patches of forest and meadow attenuate snow melt and runoff, helping to regulate the mountain water cycle.

With milking time coming up, a herd of goats heads through the pasture back toward the stall. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

The daily dose of special sauce at the Kapler Alm, in Lower Austria. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

But global warming and other human impacts are threatening that delicate balance. With temperatures expected climb at least another one to two degrees Celsius by late century, mountain farmers are facing huge challenges. Austria, two-thirds of which is part of the Alps, has warmed more than twice the pace of the global average — two degrees Celsius compared to the global average of 0.85 degrees Celsius, according to Nebojsa Nakicenovic, director of the Vienna-based International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis. Another 1.5 degrees warming by 2050 is already baked into the system; herders who have been tending livestock for a few decades are already feeling the heat.

“Every year, the snow melts earlier. It’s warmer in the spring. That means you have to move the cows up earlier in the year, or the grass gets too long,” says JürgenSchreuder, an Austrian cowboy who is tending about 100 cows at the 754-meter Kapler Alm, near Gaming in Lower Austria.

Schreuder wears acid washed jeans and a glittery disco T-shirt as he slops out portions of salt to a herd of about 100 cows. Taking a break, he offers us an early afternoon shot of schnapps, not an uncommon greeting on an Alm. As the cows wander off, Schreuder tells us he’s been tending cattle and making cheese in the mountains for 30 years.

“When it rains, it rains harder. When it gets hot, it’s hotter and the dry times are getting longer, sometimes for weeks. When the summer rains stop, the grass turns brown and it’s hard to feed the cows,” he says, describing a pattern that’s become common across parts of the Alps, but not everywhere.

Italian mountain researchers have documented a surge in global warming in the Alps, one that started about 30 years ago. During that span, the number of snow-covered days across most of the Swiss Alps declined by 29, and the maximum seasonal snow depth at a number of different measuring stations dropped by 25 percent. Other studies show intensifying heatwaves in the Alps, as well as more droughts in recent decades. The effects could be nuanced, with more rainfall north of the main alpine crest but a tendency toward drought on the southern face of the range.

Textured hay meadow in the subalpine mountains of Lower Austria. (Photo: Bob Berwyn)

Alpine pastures provide habitat for rare orchid species and pollinators. There are two different species of bugs on each of the blossoms in the bottom pictures. (Photos: Bob Berwyn)

A changing climate is definitely part of the challenge for sustainable mountain farming in Austria, says Innsbruck University agriculture researcher Markus Schermer.

With warmer temperatures, forest are advancing up mountain slopes. Grazing would help check that increase of the timberline, but requires an adjustment of practices, including timing. In France, mountain researchers have found climate change impacts to permanent grasslands, including more frequent drought and volatility in rainfall patterns. Those findings suggest that higher pastures may become more important in the future, Schermer explains.

“What I can observe is farmers are thinking about how to use excess water, when it comes, for irrigation, like they do in the southern Alps already with reservoirs,” Schermer says. “ So far, this irrigation is not something we do in the northern Alps.” He suggests developing storage and irrigation infrastructure for times of need as soon as possible.

“You can’t see the Alm as disconnected from what happens lower in the valley. If you don’t have enough lowland fodder to keep enough animals in the winter, you won’t have animals to send to Alm in the summer. But there are other drivers than climate change putting more immediate strain on the system,” Schermer says. “The decline of milk prices puts more pressure, for example, that overshadows the discourse on climate change, and the institutional support is far more to mitigate the immediate problems the farmers are facing, rather than long-term adaptation.”

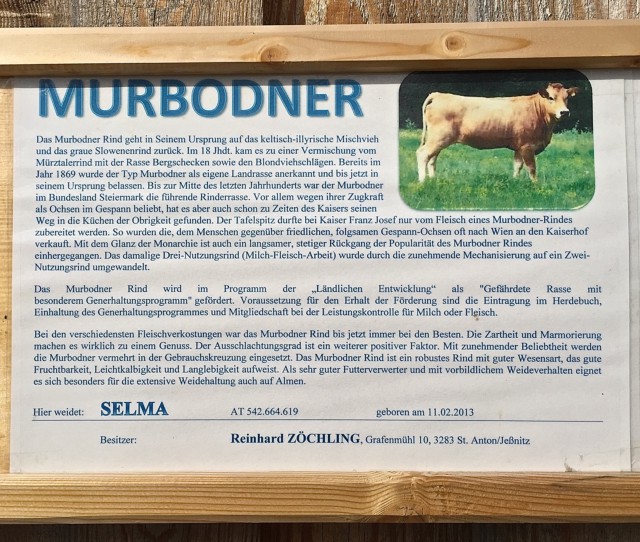

Some Austrian cattle’s lineage can be traced back to Celtic-Illyrian stock. (Photos: Bob Berwyn)

The story was made possible in part through support from the Earth Journalism Network and Internews.