When you look for them, gender gaps seem to be almost everywhere, from athletic performance to workplace earnings to college integration. What’s more, they appear to be connected.

By Tristan Bridges

Machinists working for Ford Motors attend a conference on equal rights on June 28th, 1968. (Photo: Bob Aylott/Keystone/Getty Images)

Gender gaps are everywhere. When we use the term, most people immediately think of gender wage gaps. But, because we perceive gender as a kind of omni-salient feature of identity, gender gaps are measured everywhere. Gender gaps refer to discrepancies between men and women in status, opportunities, attitudes, demonstrated abilities, and more. A great deal of research focuses on gender gaps because they are understood to be the products of social, not biological, engineering. Gender gaps are so pervasive that, each year, the World Economic Forum produces a report on the topic: “The Global Gender Gap Report.”

I first thought about this idea after reading some work by Virginia Rutter on this issue (here and here) and discussing it with her. When you look for them, gender gaps seem to be almost everywhere. As gender equality became something understood as having to do with just about every element of the human experience, we’ve been chipping away at all sorts of forms of gender inequality. And yet, as Rutter points out, we have yet to see gender convergence on all manner of measures. Indeed, progress on many measures has slowed, halted, or taken steps in the opposite direction, prompting some to label the gender revolution “stalled.” And in many cases, the “stall” starts right around 1980. For instance, Paula England showed that, though the percentage of women employed in the United States has grown significantly since the 1960s, that progress starts to slow in the ’80s. Similarly, in the 1970s a great deal of progress was made in desegregating fields of study in college. But, by the early 1980s, about all the change that has been made had been made already. Changes in the men’s and women’s median wages have shown an incredibly persistent gender gap.

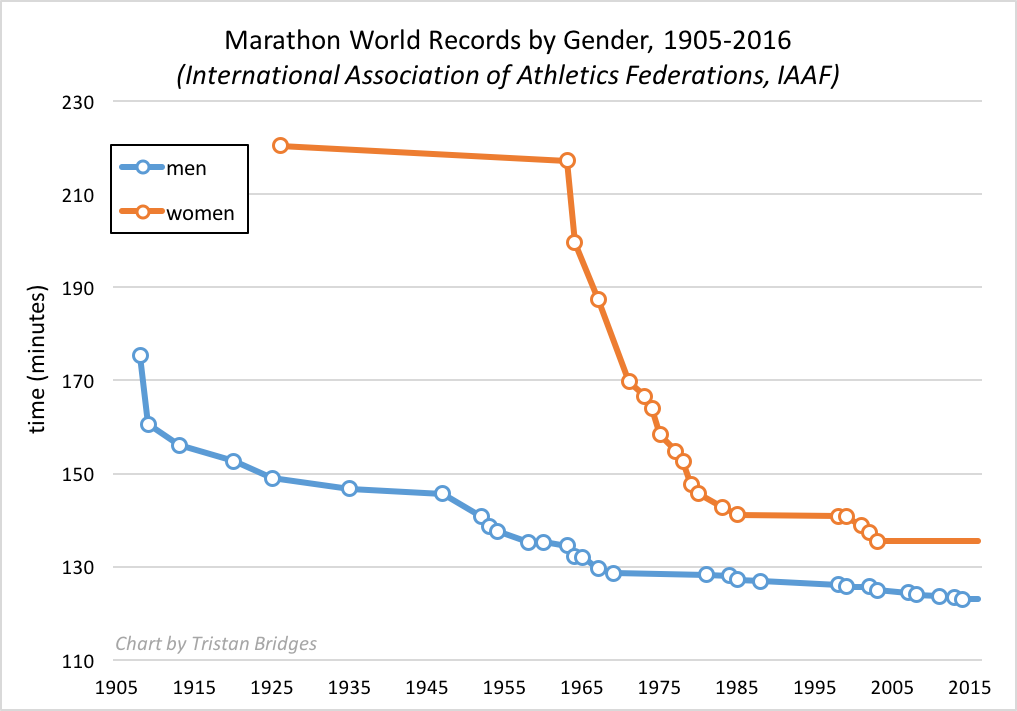

A set of gender gaps often used to discuss inherent differences between men and women are gaps in athletic performance — particularly in events in which we can achieve some kind of objective measure of athleticism. In Lisa Wade and Myra Marx Ferree’s Gender: Ideas, Interactions, Institutions, they use the marathon as an example of how much society can engineer and exaggerate gender gaps. They chart world record times for women and men in the marathon over a century. I reproduced their chart below using IAAF data.

In 1963, an American woman, Merry Lepper, ran a world-record-breaking marathon at 3 hours, 37 minutes, and 7 seconds. That same year, the world record was broken among men at 2 hours, 14 minutes, and 28 seconds. His time was more than 80 minutes faster than hers! The gender gap in marathon records was enormous. A gap still exists today, but the story told by the graph is one of convergence. And yet, I keep thinking about Rutter’s focus on the gap itself. I ran the numbers on world-record progressions for a whole collection of track-and-field races for women and men. Wade and Ferree’s use of the marathon is probably the best example because the convergence is so stark. But, the stall in progress for every race I charted was the same: incredible progress is made right through about 1980 and then progress stalls and a stubborn gap remains.

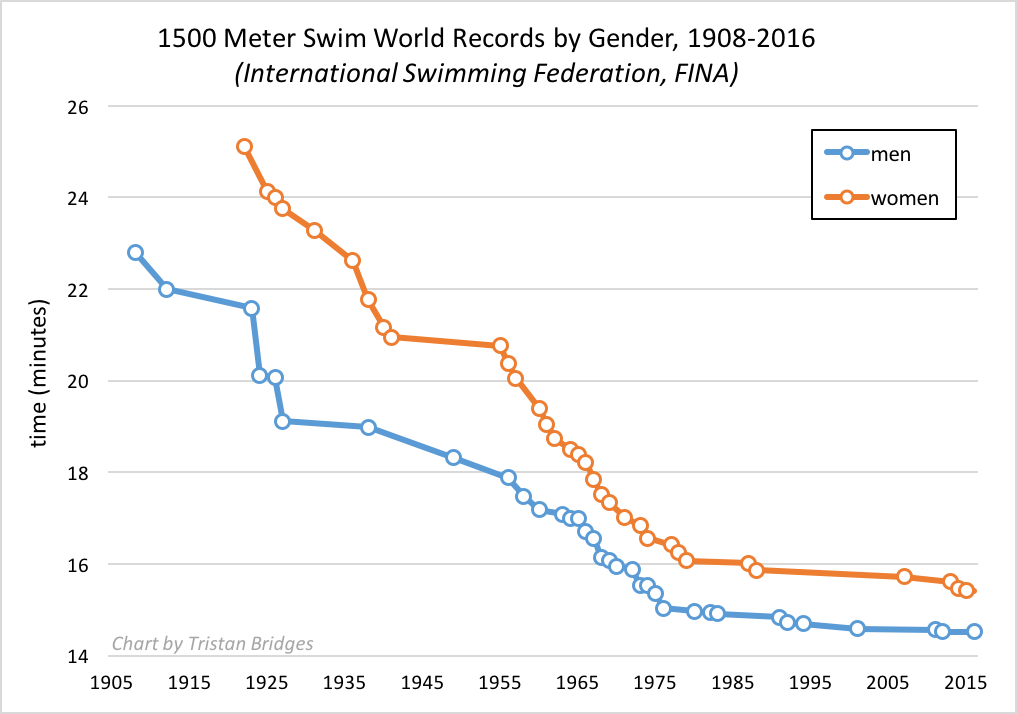

Just for fun, I thought about considering other sports to see if gender gaps converged in similar ways. Below is the world-record progression for men and women in a distance swimming event — the 1,500-meter swim.

The story for the gender gap in the 1,500-meter swim is a bit different. The gender gap was smaller to begin with and was primarily closed in the 1950s and early ’60s. Both men and women continued to clock world record swims between the mid-1950s and 1980 and then progress toward faster times stalled out for both men and women at around that time.

One way to read these two charts is to suggest that technological innovations and improvements in the science of sports training meant that we came closer to achieving, possibly, the pinnacle of human abilities through the 1980s. At some point, you might imagine, we simply bumped up against what is biologically possible for the human body to accomplish. The remaining gap between women and men, you might suggest, is natural. Here’s where I get stuck: What if all these gaps are related to one another? There’s no biological reason that women’s entry into the labor force should have stalled at basically the same time as progress toward gender integration in college majors, all while women’s incredible gender convergence in all manner of athletic pursuits seemed to suddenly lose steam. If all of these things are connected, it’s for social, not biological, reasons.

This story originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “Gender Gaps and the Stalled Gender Revolution.”