From Schindler’s List to Hotel Rwanda, films about genocide tend to focus on immediate victims. But in three documentaries following up on the 1965–66 mass killings in Indonesia, director Joshua Oppenheimer tells the contemporary stories of those who survived, only to suffer its lingering effects. In 2003’s The Globalization Tapes, which Oppenheimer produced in collaboration with a plantation workers’ union in Sumatra, workers demonstrate how the genocide served, in part, to end anti-colonial labor movements — and how its fallout still limits their attempts to organize. The Act of Killing (2012) depicts how contemporary Indonesian authorities portray the traumatic event as a historic success for national security, while 2014’s The Look of Silencetraces what this political and social upheaval has meant for one man: an optometrist making house visits to the men who killed his brother. The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence collectively won 145 international film awards; in 2014, Oppenheimer won a MacArthur “genius grant.”

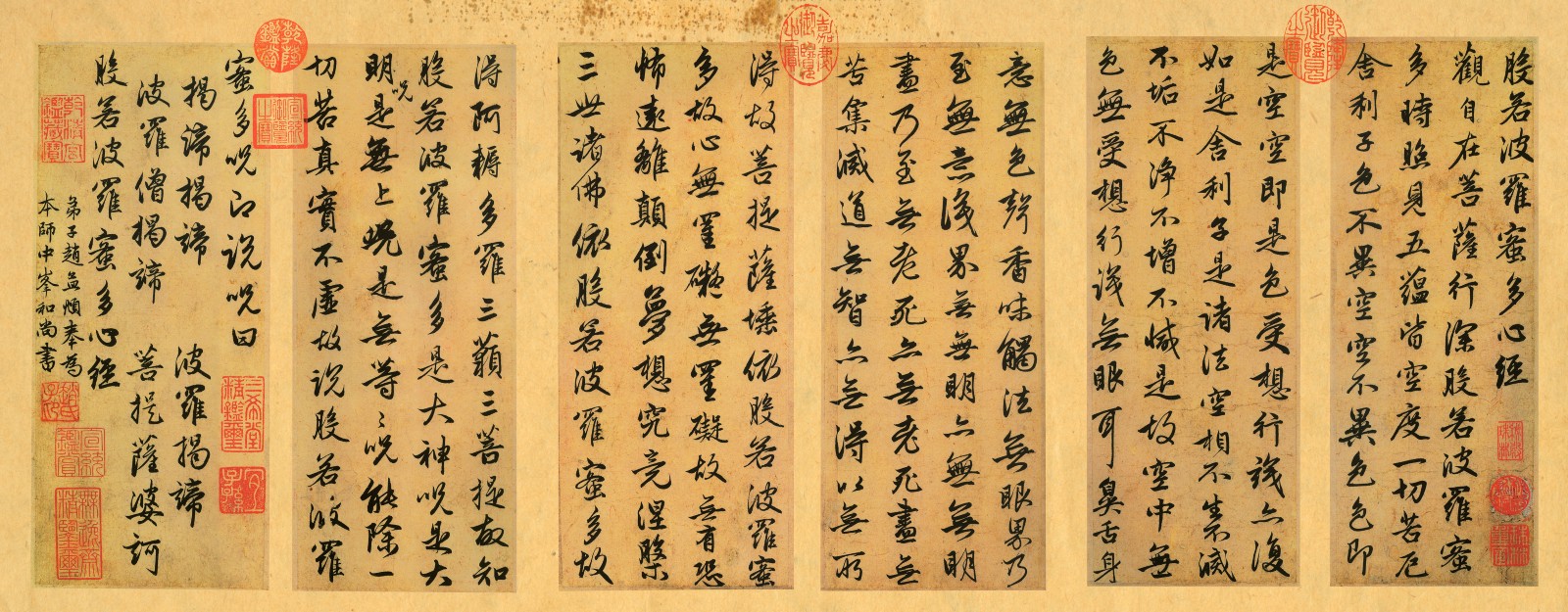

Scripture

The Heart Sutra

Buddhist scholars often describe The Heart Sutra as the most popular, concise, and beloved sutra in Mahayana Buddhism. Over the course of a very short text — only 35 lines in the 2005 Red Pine English translation — the sutra outlines several of the tradition’s core principles and particularly distinguishes between “form” (how humans view reality when they are not enlightened) and “emptiness” (their perceptions when they are). “It’s a kind of distillation of the most intricate metaphysics of interconnectedness,” Oppenheimer says.

Why

“The thing that always troubled me until I discovered The Heart Sutra was the potential for ethical relativism. But why do we have ethics? Why do we have morality? Why do we care for others, if the universe beyond our perception is something unknowable and un-graspable? The Heart Sutra very carefully, delicately, and tenderly, but also very succinctly, creates an ethics out of our interconnectedness.”

Films

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Released two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis and around five before the East-West détente, director Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 black comedy lampooned Cold War-era hawkishness at a time when it posed a serious threat to the international community. The film follows the fallout from a deranged Air Force general’s (Sterling Hayden) decision to order several B-52 bombers to attack the Soviet Union — forcing the United States president, his ex-Nazi strategic advisor (both Peter Sellers), and the Soviet ambassador (Peter Bull) to convene in his War Room and determine how to prevent seemingly imminent annihilation.

Why

“It’s easy to forget, because of climate change or because of the post-Cold War chaos that we suffer in, that we still have the weapons to destroy ourselves again and again and again, and demolish the planet multiple times over. There’s no more unflinching look at how we, as a species, seem hell-bent at destroying ourselves out of sheer stupidity than Kubrick’s film. And no better warning.”

Salaam Cinema

Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf originally envisioned 1995’s Salaam Cinema (which translates to Hello Cinema in English) as a conventionally cast feature film celebrating the 100th anniversary of cinema, but when 5,000 people showed up for the audition to get a part, he turned the film into a documentary about the casting call itself. As he interviews (and brutally directs) his wannabe actors, Makhmalbaf nevertheless uncovers the peculiar nature of Iranian cinephilia — “what cinema means to this society,” as Oppenheimer says.

Why

“What unfolds is this very precise, very devastating look at power and the director’s role as an allegory for the dictator. Mohsin Makhmalbaf has a deep humanity; though he’s playing with these people, you sense this deep place of love from which this whole film is being made. In our era of reality television and media stars who are desperate to make it, and stage themselves in life to become celebrities, Salaam Cinema is really prescient, and all the more amazing for being from Iran in the 1990s.”

Even Dwarfs Started Small

All the characters and actors in Werner Herzog’s surrealist 1970 comedy-drama, set at a bureaucratic correctional institution on a remote island as the inmates rise up against the guards, are little people. The institution, however, features furniture that’s built and scaled for full-sized adults — such that “you feel how we are dwarfed by the power structures around us,” Oppenheimer says.

Why

“These are images that we dream of and leave us unsettled in the morning and with a strange taste in our mouths or a ringing in our ears; and here they are unfolding in the most physical, luminous, black-and-white scenes. It’s just the closest you can come to seeing on film a kind of fever dream about power and human freedom. But this is not an optimistic view of human freedom.”

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

Contrary to movie musicalsthat incorporate their numbers between spoken interludes, all of the dialogue inJacque Démy’s 1964 film is sung, even the script’s most nonchalant conversations. The film, a coming-of-age tale about a young French girl (Catherine Deneuve) who must grow up when her lover is shipped off to war in Algeria, is “a real recovery of innocence,” Oppenheimer says, because every character is constantly breaking out into song.

Why

“The film is beautiful and tragic and people get hurt, but they never willfully hurt one another. I think it’s a great corrective to our tendency to divide the world into good guys and bad guys. That tendency is the ultimate form of escapism because it prevents us from actually looking at how we might be responsible for problems ourselves.”

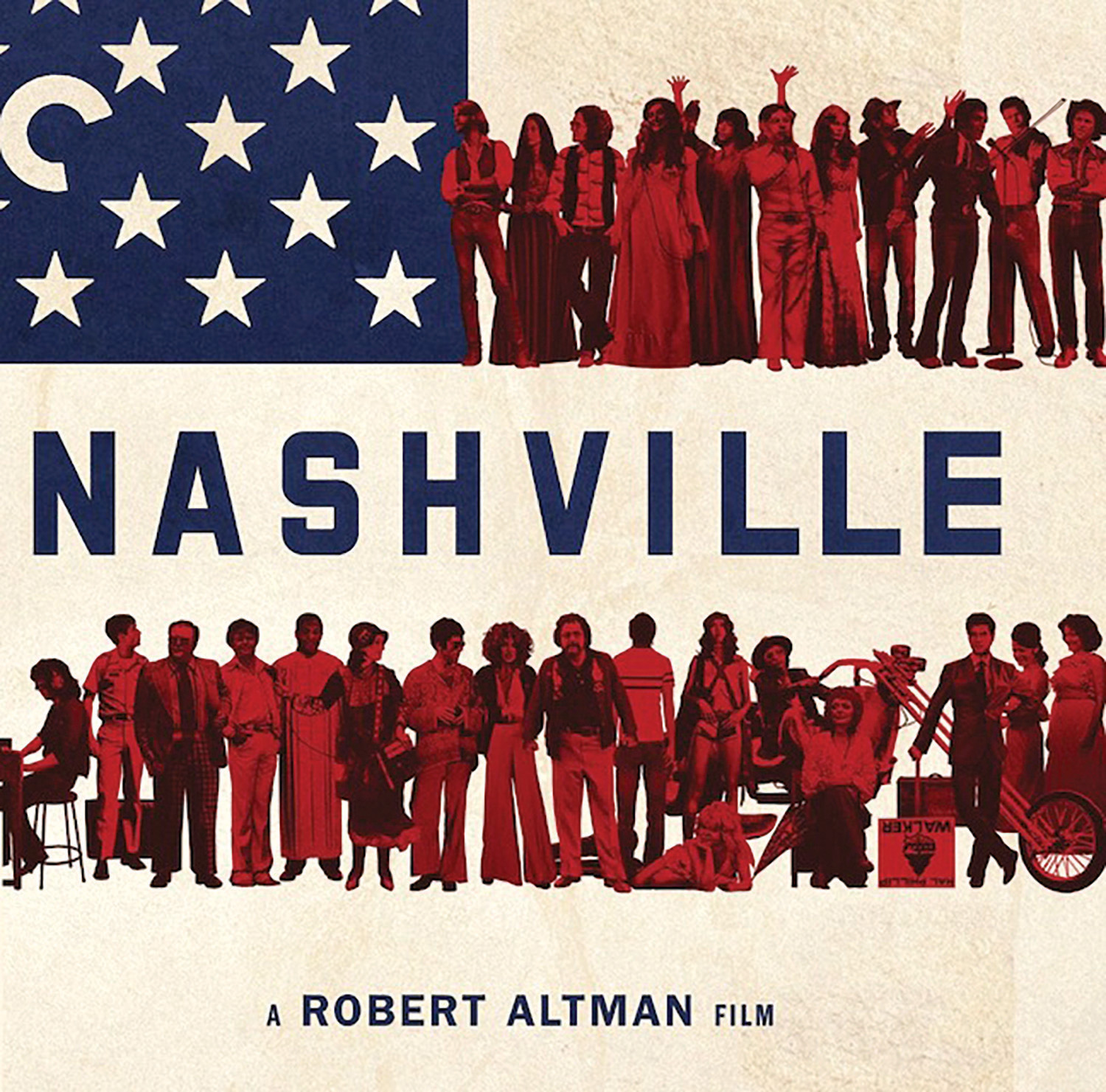

Nashville

Director Robert Altman’s sprawling 1975 musical comedy-drama epic follows around two dozen characters — including a reporter, a waitress, and a country star — as they cross paths with one another over the course of five days preceding a political rally. The film, which features several songs written and performed live by the movie’s cast, was nominated for five Oscars and was selected for preservation in the Library of Congress by the National Film Registry in 1992.

Why

“Nashville is on my mind because we’re in a presidential election year. If you watch Nashville today, it reflects what we have been becoming and now, alarmingly, have surpassed. It’s also a very human film; everybody is complicated and richly characterized. It’s one of the best American films ever made.”

Play

Happy Days

In the first act of Samuel Beckett’s 1961 play, a woman is buried to her waist in sand in a bleak desert while her husband moves freely behind her, appearing occasionally to offer her solace (her hands are free, and a gun is in reach) and company. By the second act, however, the woman, buried to her neck, cannot turn her head to see him anymore or use her hands to reach the gun. She nevertheless remains “desperately optimistic,” Oppenheimer says.

Why

“As an American living in Europe, I’ve become more aware of the way in which we Americans have this kind of completely misbegotten optimism in the face of situations where we would do well to acknowledge, soberly and honestly, the scale of our problems. Happy Days holds a mirror up to the ways in which we lie to ourselves and pretend everything’s all right. It suggests that perhaps the proper solution in the face of pain, suffering, mortality, and, ultimately, extinction, is some form of acceptance.”

Literature

The U.S.A. Trilogy

John Dos Passos’ epic, 1,240-page trilogy — comprising the novels The 42nd Parallel (1930), 1919 (1932), and The Big Money (1936) — begins at the outset of World War I and ends with the 1929 stock market crash (a coda takes place during the Depression). The trilogy employs four distinct writing styles: The most conventional interweaves the stories of 12 characters; others move the story forward through a collage of newspaper clippings and song lyrics, short biographies of major public figures, and stream-of-consciousness writing.

Why

“[Dos Passos] was a progressive who became very right-wing in the McCarthy era, and fell out of favor as a result. U.S.A. was forgotten, but it shouldn’t have been: It’s one of the most morally clear visions of the tragedy of American greed and American oligarchy. It [follows events] leading up to the 1920s stock market bubble and crash, a phenomenon that again brutalizes our society. It’s a work in which you always find yourself and your time.”

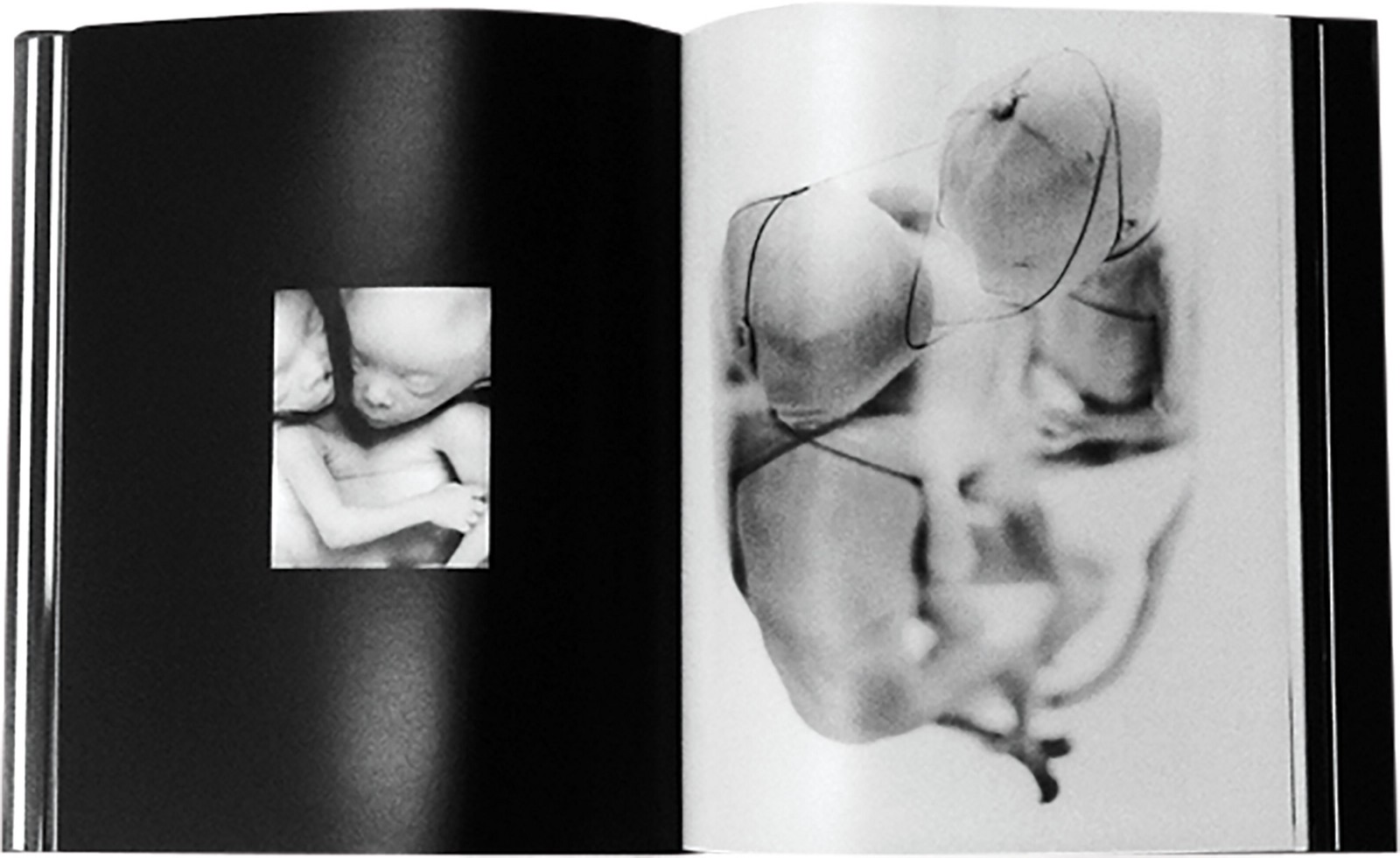

Photography

Lost Souls

In this reproduction of prints from her 2010 International Center of Photography exhibit of the same name, Lena Herzog presents haunting images from “cabinets of wonder and curiosities”—collections that preserve anatomical specimens and oddities for study, which first came into vogue in the 17th century. The title refers to a term that 18th-century Russian Orthodox monks used to describe some of the photos’ subjects, which include Siamese twins, unborn fetuses, and cyclopic babies — conveying they would not gain access to heaven, hell, or limbo, and were therefore doomed.

Why

“It’s a collection of photographs that gives me goosebumps because it reminds me that everything that manifests before our eyes is completely and utterly mysterious. In a time when we’re almost imprisoned by the tyranny of images, it’s easy to forget that these images are all haunted by their own unreality — that they are only images. Here’s an attempt to use imagery to remind us that what seems present might not be, and what seems alive might be illusory.”

Sonata

Imitazione Delle Campane

German Baroque composer Johann Paul von Westoff was a 17th-century violin virtuoso, linguist, and composer at the Weimar court whose solo violin partitas, according to musicologist Christoph Wolff, were “the first of [their] kind.” One of these, his two-minute-long “Imitazione delle Campane” was composed in 1694 in Dresden.

Why

“When played as a solo, it’s like infinity and pure energy coming out of one violin. You can’t believe what you’re hearing, the majesty of this simple composition. It invites you in to make the music with it as you fill in all the empty space that normally other instruments would be playing. I probably listen to it five times a week.”