Herbert Manown is a self-described “jack-of-all-trades but master of none.” A Harley Davidson-riding Vietnam War Navy veteran, he has worked in construction, at the post office, and with the United States Census Bureau. At 62, he’s still fit and healthy, with a strong handshake and grandfatherly eyes framed by black glasses and thick, bushy brows.

Life was stable for Herb until 2013, when he “got lazy” and neglected to renew his truck-driver license. He didn’t realize the severity of his error until he applied for a new license but could not pass the written test. Although Herb quickly landed a job as a security guard at a fast-food restaurant, even working overtime didn’t provide enough for him to make ends meet. He fell behind on rent and was evicted.

Herb has four children in the Bay Area, but he was reluctant to ask if he could move in with any of them. As he put it, “We have very different lifestyles.” And while he also has siblings in the area, they had a major falling out, so he refuses to turn to them for help. He wound up settling in at the East Oakland Community Project, a shelter located near his old apartment. He volunteered in the kitchen and was even voted president of the shelter, a position that entails acting as a go-between for residents and management. But after a few months, he felt pressure to move on. “Herb, you have to go,” he recalls them saying. So he bought a used car and moved into it.

The circumstances that led to Herb’s eviction — living check to check, with rent taking up a disproportionate amount of earnings — are distressingly commonplace in the U.S. One-third of adults aged 50 or older spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing, according to a 2014 report. And the housing market in this country is unforgiving to those who cannot pay. Meanwhile, the average age of the nation’s homeless population is increasing faster than that of the general public. In 1990, an estimated 11 percent of the adult homeless population was over the age of 50. By 2003, that number had increased to 32 percent. Today, researchers put the figure closer to 40 percent — and rising.

“We’re on a collision course that’s going to get worse and worse unless we do something about it,” says Doug Shoemaker, president of Mercy Housing California, a non-profit dedicated to providing affordable housing. Because few safety nets exist for low-income, aging individuals, he says, “the door into homelessness is wide open.”

But fixing a broken system first requires understanding the ways in which it is broken. Margot Kushel, a physician and professor of medicine at the University of California–San Francisco and San Francisco General Hospital, is one of the few people confronting this mammoth task.

Kushel never planned to become an authority on homelessness, but her experience as a resident at San Francisco General in 1995 had a profound impact. Nothing in medical school had prepared her for the fact that roughly half of her patients were homeless. They came to her in appalling condition — the victims of accidents or debilitating illnesses — and she would do what she could to patch them up. Compared to other patients, their hospital stays tended to be inordinately long — a patient with an oxygen tank cannot be discharged to the streets, after all — and, as a result, inordinately expensive. Patients who were homeless also tended to come back to the hospital again and again for the same problems.

She grew frustrated at her inability to provide meaningful help, and deeply distressed over what she perceived as a “nonsensical” treatment approach: one that boiled down to “very, very expensive Band-Aids” that neglected to consider the root causes.

As the years passed, one obvious trend emerged: Her homeless patients were getting older. But why? And what could be done to help them?

Finding those answers became something of an obsession for Kushel. “As a human being, it was horrifying to me to think that we have these older people in the street,” she says. “It’s just unconscionable.” In 2013, after years of trying, she finally convinced the National Institute on Aging to fund a multi-year study of homelessness in people over 50.

Kushel probably knows more about the nation’s aging homeless population than anyone. Energetic, affable, and in possession of an uncanny ability to explain complex issues in a compelling and understandable way, she can often be found evangelizing about the challenges — and solutions — of homelessness among older individuals. Along with hoop earrings and glasses, Kushel likes to wear a marbled turquoise-and-purple scarf that a formerly homeless man in his 70s made for her. Now, he’s off the streets and teaching art. “To me, this scarf represents what can go right,” she says. “This is not a monolithic problem, and with enough political will, we could change it.”

Already, her study’s preliminary results have flown in the face of many stereotypes about homeless people, including the idea that homelessness is primarily a consequence of addiction or psychiatric problems. Instead, Kushel has found that nearly half of her participants worked throughout their adult lives and only became homeless in their later years, usually because of a sudden, unfortunate event such as the loss of a job or the death of a spouse. Like Herb, they are often victims of bad luck, tragedy, a tough economy, or some combination thereof.

“Someone once told me,” Herb says, “almost everyone is just one paycheck away from being homeless.”

On a sunny Wednesday morning, a group of elderly men and women — some wearing visors and dark glasses, others leaning on walkers — slowly make their way into St. Mary’s Center, a non-profit space in Oakland where low-income seniors can hang out and grab a bite to eat, use a computer, read, or make art. Those in need can take advantage of additional social services, including help filling out paperwork and seeking placement in the beguiling affordable-housing system. In the winter, St. Mary’s also acts as an emergency shelter.

Buffered by a neatly pruned garden complete with shade trees and benches, the entrance to St. Mary’s contrasts sharply with the boarded-up windows, litter, graffiti, and homeless encampments that otherwise characterize this westerly section of Oakland. Kushel chose to base her study here because the city is more nationally representative in terms of economics and available services than neighboring San Francisco.

The main room at St. Mary’s looks a bit like a high school gym or cafeteria, with pale wooden floors, circular tables, and plastic chairs. And just as high schoolers would do, arriving seniors beeline for their favored tables — a group of Vietnamese ladies here, a raucous team of dominoes players there. Some snap up free pastries and cups of strong coffee set out on big, welcoming trays. In a far corner of the room, in what appears to be a tall, narrow closet, Kushel’s colleagues meet with study subjects at six-month intervals to get an update on their situations and see how they are faring mentally and physically. Monthly check-ins are also highly encouraged, though only around 45 percent of study subjects actually show up that often (the rest are typically tracked by phone).

Pamela Olsen, a private investigator turned clinical research coordinator, spent a year helping to recruit the original group of 350 study participants. She visited food banks and encampments, recycling centers and shelters, handing out bus passes to those who signed up. Most cannot afford the $2.50 fare to reach the study center, and the promise of unlimited transportation for a day tended to serve as an enticement. The criteria for entry into the study were straightforward: individuals aged 50 or older who were homeless and able to communicate clearly in English (some could not due to language barriers or hearing problems). The final study group had a median age of 58, though some were as old as 80.

Participants first went through an exhaustive interview about their lives, including history of mental-health issues, cigarette smoking, and substance use, and details of their family relations, jobs, access to health care, living conditions, and more. They were asked about the circumstances that led them to become homeless, and to describe what their lives had been like since then. Their mental and physical states were evaluated through standardized written and physical tests, most of which are repeated at each six-month review, allowing the researchers to track an individual’s health over time. This data has revealed a disturbing but hardly surprising finding: The longer a person spends on the street, the worse his or her condition becomes. Kushel has already used this information to provide testimony to the California State Senate, and she expects the study’s long-term findings to identify a need for more effectively designed services that take geriatric individuals into account.

Today is a slow day, and the study staff busy themselves folding socks (which they hand out to participants) and transcribing data. Eventually, a woman with a Liza Minnelli bob and bright pink sneakers approaches the table. “Everyone is smiling today!” she says, beaming. “That’s because you came in!” replies John Weeks, another UCSF clinical research coordinator who works on the study full time.

Olsen takes the woman, who is here for her six-month interview, into a private room, where she evaluates her cognitive skills and executive function through a series of questions and activities, from asking her to name animals with four legs to challenging her to fit a series of pegs into a board with corresponding holes. Olsen also performs physical tests, including measuring the woman’s grip strength, balance, and walking speed. At the end of the process, the woman receives a $15 gift card, which she can use at a grocery store or Walgreens. Olsen and Weeks bid her goodbye, hoping the next time they see her she might have good news about finding housing or moving in with a relative. Statistically speaking, though, her odds are not high.

Cherie Manown has grown tired of shelter life. “There don’t be nothing to do here,” declares the 55-year-old San Francisco native. She decided to join Kushel’s study for the freebie perks — as well as just for a change of scenery. Deep lines between her eyes reveal a lifetime of stress and worry, but when she smiles, 20 years melt away, and her dimples and twinkling brown eyes make her appear almost girlish.

Cherie has been in and out of homelessness for much of her life. For a time she lived with her mother, but after her mom suffered a fatal heart attack, the house was foreclosed. Things got worse from there. In 2010, deep in the throes of alcoholism and a crack-cocaine addiction, she was staying with her nephew when a man came to fetch her from the house. Although she sensed that “something was going on, something was not right,” she could not manage to extricate herself from the situation. That’s when she saw the gun: A boy carrying a 9-millimeter rounded the corner. He shot Cherie seven times. Somehow, she survived. (The boy, who was later arrested and turned out to be just 14 years old, said he was using Cherie as his initiation into a gang, which required a kill for admittance.) She’d been bouncing around shelters ever since leaving the hospital.

Cherie’s life circumstances reflect a wider phenomenon that puts her generation at a disproportionally high risk for homelessness. In the late 1980s, Dennis Culhane, the Dana and Andrew Stone Professor of Social Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, noticed an uptick in the number of young adults on the street. In the years that followed, Culhane monitored the trend, eventually finding that late Baby Boomers like Cherie — those born between 1955 and 1965 — made up the largest subpopulation of the nation’s chronic homeless population, now comprising an estimated 40 percent.

Culhane believes a number of factors have contributed to this situation, but that the key one was an excess labor supply at the time late Baby Boomers first entered the job market, making it more difficult for them to establish careers. The reverberations were severe: In 1982, the unemployment rate for African Americans topped 20 percent. Late Baby Boomers also faced a crowded housing market, a recession, and the crack-cocaine epidemic. For many, the combination of those accumulated risks led to chronic or intermittent homelessness.

Cherie is no longer addicted to drugs or alcohol, and she does not suffer from mental-health problems. Because she doesn’t have a disabling condition, she will be unlikely to find permanent shelter through Housing First programs — subsidized living spaces with on-site treatment services that do not require sobriety as a condition of entry. Recovered individuals and those who have never suffered from chronic homelessness and addiction are rarely prioritized for Housing First assistance. Nearly half of Kushel’s study participants meet that description.

Though many have struggled with homelessness since their 20s, a shocking 43 percent of study participants had never been homeless before the age of 50. They are people who have worked their whole lives, have paid their rent or mortgage, and have no significant mental-health or substance-abuse problems. They are oftentimes parents and grandparents who are on good terms with their families. Crucially, though, as they approached retirement age, something happened: the death of a spouse or parent who was paying the mortgage or contributing to rent; a divorce that forced them to leave their home; or the loss of a job. Some were laid off during the Great Recession, while others could no longer keep up with physically taxing work and struggled to find new jobs as a result of their age. Any older person without significant savings who encounters such an event can be easily forced into homelessness.

Which is exactly what happened to Herb Manown. The fact that Herb is still in touch with his family is not exceptional among Kushel’s participants. Contrary to common stereotypes — that the homeless are socially isolated, with no friends or family — 60 percent of Kushel’s participants were able to give her contact information for a family member, and 53 percent reported having stayed with family or friends in the past six months. Like Herb, some prefer not to stay with relatives, but, in other cases, families would like to help but barely have the means to survive on their own. Cherie briefly stayed with one of her three sons, but she felt like a burden and says she will not do it again.

No programs exist for subsidizing costs for families who take in a homeless relative, with one exception: If a family member acts as a caretaker for an older relative who otherwise would need institutional services, they can qualify for some benefits through Medicaid. But Kushel has found that even those who have Medicaid usually do not receive this benefit, likely because they do not know it exists.

For some, Supplemental Security Income, a Social Security program available for low-income individuals who are disabled or over the age of 65, is intended to cover basic needs like housing, food, and clothing, and, in many states, it includes automatic qualification for Medicaid. But the level of support it provides — a maximum monthly payment of $739 for an individual and $1,109 for a couple — does not reflect the economic realities of many U.S. cities. And Kushel has also found that many older homeless individuals are not receiving these benefits, because they have not gone through the eligibility process.

Acknowledging high costs of living, some states pay a supplement on top of the federal SSI. In California, that figure is $161 per month for individuals and $408 for couples in 2017 (though it has decreased significantly since 2009, when it was $233 and $568, respectively). But fair-market rent for a one-bedroom in San Francisco or Alameda County stands at around $1,800 and $1,700, respectively — more than a couple’s combined SSI and supplemental state income.

“A poor person living on Social Security in San Francisco will never ever be able to afford their own apartment,” says Joshua Bamberger, a physician and professor at UCSF and chief medical consultant at Mercy Housing. “If we continue to think that this problem will get better without governmental intervention, we’re living in a fantasy.”

California Governor Jerry Brown included a modest increase in the state’s supplemental payment in his January 2016 budget, but the amount does not even approach pre-recession levels. In 2009, California repealed its cost-of-living adjustment, an annual budgetary tweak that ensured the state’s supplemental payments reflected real-world costs of living. “The governor of course is very shy to agree to much of any increase to ongoing costs,” says Mark Leno, who represents the 11th Senate district of California, which includes San Francisco. “But it is certainly exacerbating the depth of poverty many Californians are living in.”

“It’s not that complicated of a problem,” says Kevin Prindiville, executive director of Justice in Aging, a non-profit dedicated to fighting senior poverty through law. “If we’re giving people well below what it costs to rent an apartment, then there are going to be people who are homeless.”

But even if social-support programs were bolstered and older homeless people provided enough income to rent a place of their own, they would still be faced with a woeful lack of affordable housing. For a hypothetical person over 50 who lost their job and was evicted from their apartment, the odds of securing an affordable unit in San Francisco are extremely slim, says Margot Antonetty, a manager at the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing. “It would be very, very difficult,” she says.

Their likelihood of finding re-employment while living on the street or in a shelter is also low, she adds. And chances are high that their health will quickly deteriorate under the stress of homelessness.

Each new building that the city’s Department of Public Health opens for seniors receives about 4,000 applications. Mercy Housing’s apartments receive around 100 applications per unit. “They say, nationally, that one in every four people that needs affordable housing gets it,” Shoemaker says. “My guess is that, in the Bay Area, that number is two to three times worse.”

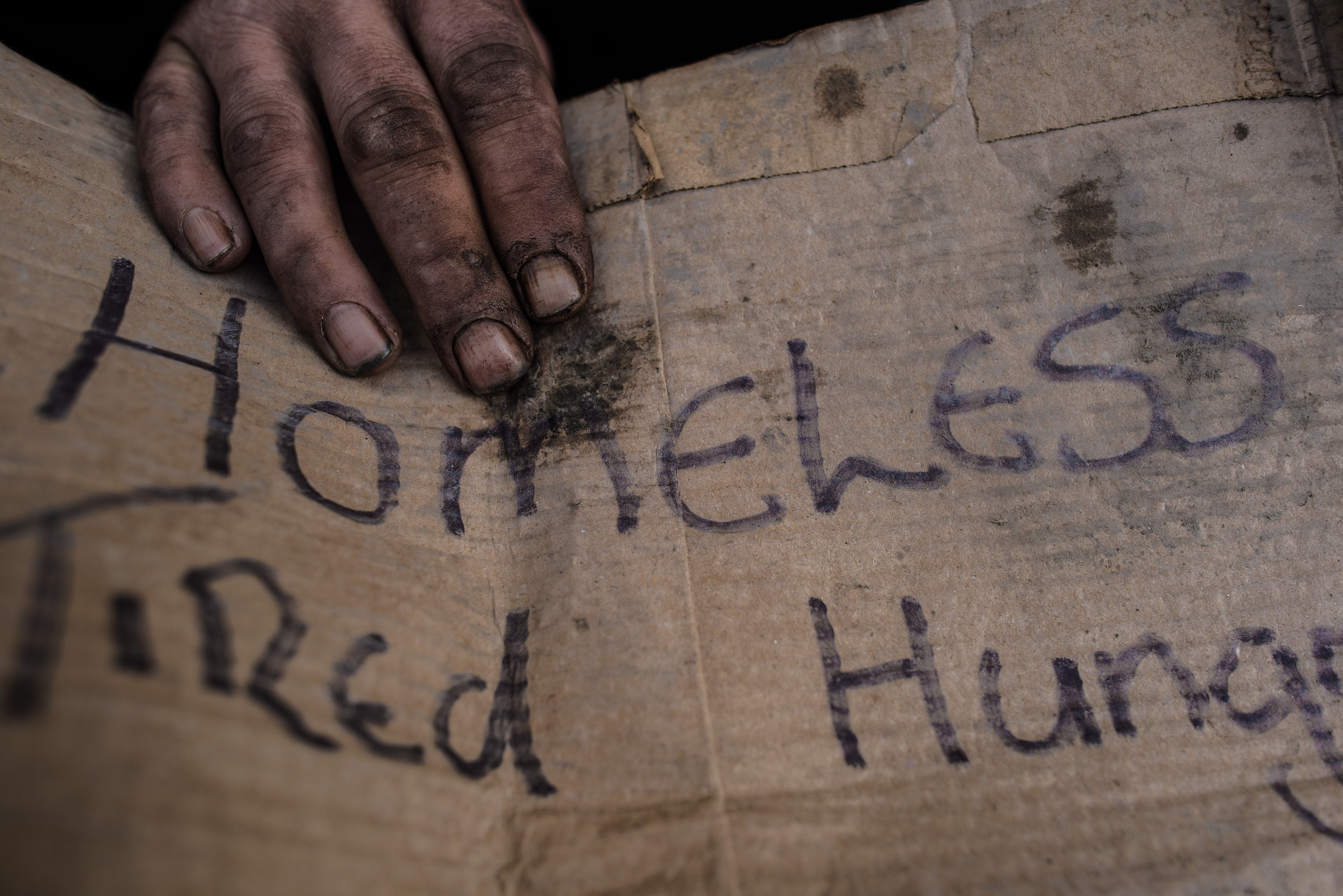

Herb experienced that unfortunate reality firsthand. Last winter, his car got towed, taking his security-guard uniform and most of his remaining possessions with it. He never got the car back — he didn’t have the funds. Unable to dress for work, he stopped going, and spent the next two months on the streets. He panhandled, flashing his veteran’s ID as he asked for spare change, and was sometimes reduced to eating out of dumpsters. To survive the winter chill, he slept bundled up in several layers of pants, shirts, and blankets. Once, a cop tried to shoo him from a doorway, and Herb begged him to take him to jail instead, so he would have a warm place to sleep. The officer told him, “I’m not taking you to jail, but you can’t stay here.”

“I was really down,” Herb says. Yet he still counted himself lucky. “A lot of the people I met on the street were on meds and should have been hospitalized,” he says. “They really couldn’t take care of themselves.” But even a strong, able-bodied person like Herb will soon be broken down under those conditions. At one point he began suffering from severe chest pains, so he checked into Oakland’s Highland Hospital, where he remained for five days. “The stress got to me,” he says. “The hospital people told me, ‘Herb, just being on the streets is messing you up.’”

Not surprisingly, older homeless people frequent emergency rooms at extremely high rates; over a six-month period, half of Kushel’s participants made such a visit. “Every story I hear in my office involves someone exposed to trauma,” says UCSF’s Joshua Bamberger, who has specialized in caring for homeless patients for 20 years. That trauma may consist of getting hit by a car, abused, or assaulted, he says, but “there’s also the daily, subtle trauma of being looked at as less than human by so many of the people who pass by my patients.”

Kushel has found evidence of accelerated aging among 39 percent of her participants — that is, their physical health reflects that of a person up to 20 years older than their chronological age. Many suffer from diabetes and heart and lung disease. They have problems with cognition, vision, falls, and incontinence. Some struggle with basic tasks such as getting dressed and following a series of instructions. That latter finding is especially worrying, given that access to social programs requires navigating a bewildering array of forms, phone calls, appointments, and deadlines.

After six months, Herb moved back into the East Oakland Community Project shelter — the minimum time allowed before re-entry. His health began to improve almost immediately. It was there that he met Cherie.

He first noticed her — really noticed her — over a game of Four Corners. “It’s her laugh,” he says. He soon won her over with potato chips and candy bars. “We just started going out,” he says. Last December, they married.

But the couple still had nowhere to live. Finding a home meant securing a housing voucher — also known as a Section 8 — a subsidy administered by the federal government and distributed locally by public-housing agencies. A person or family who receives a voucher has a finite period of time to find a place to live, and the rent for the home must fall under a certain amount. Generally, the occupant pays 30 percent of their monthly adjusted income (if it’s zero, they pay zero), and the voucher covers the difference.

This type of aid is estimated to serve only a quarter of those who qualify, however, and that problem is even more pronounced in hot housing markets like the Bay Area. The website of the San Francisco Housing Authority warns Section 8 applicants that they may be on the wait list for four to nine years. And some landlords refuse to take Section 8 vouchers. “Imagine waiting all of those years to get a voucher and, once you have one, you can’t even use it,” says Mark Leno, who has proposed a bill that would prevent landlords from discounting housing vouchers as a valid source of income.

Cherie’s odds of securing a Section 8 were close to zero, but, as a veteran, Herb stood a fair chance. In 2010, President Barack Obama launched an initiative to end homelessness among veterans, greatly expanding funding toward that goal (with $534 million in spending from the Department of Veterans Affairs that first year, and $1.6 billion budgeted for 2017). The VA went to work implementing several research-backed solutions for getting veterans off the streets and preventing at-risk individuals from losing their homes in the first place. Part of this work involved developing analytic models for predicting who is most at risk of becoming homeless, of returning to homelessness, and of suffering adverse outcomes while homeless, and then ensuring those potential outcomes do not play out.

The VA also studied subpopulations of homeless veterans, including women, and used in-depth program evaluations to create population-tailored housing and care options for getting them off the streets.

As a result, the number of homeless veterans decreased nearly 50 percent from 2010 to 2016, with cities such as New Orleans and Salt Lake City having effectively ended homelessness among veterans. “The political leadership and support that has allowed the VA to really take on this issue, to make a difference, and hold people accountable for outcomes, has been critical and can’t be overstated,” says Thomas O’Toole, director of the National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans and a professor of medicine at Brown University. Kushel sees the VA’s success as a model for what could be. “If the same political will was applied to the rest of the homeless population, this could be fixed,” she says.

Last March, Herb hit the jackpot, acquiring a couple’s voucher through the VA. Although he and Cherie were allotted just four months to secure housing, they were hopeful. Each day, Cherie scoured the apartment listings on Craigslist. They put their names on several wait lists.

Just before the voucher expired, the couple found a one-bedroom on the fourth floor of a building dedicated to providing housing for senior citizens. They pay just $245 per month, while the VA contributes $1,500. Herb’s mother, who has advanced Alzheimer’s disease, moved in with them for a few months, so he and Cherie had their hands full for a while. Still, they couldn’t be happier. “It’s a very nice place, and we have a pretty good view too,” Herb says. “We can see for blocks and blocks and blocks.” Once things settle down, Herb plans to find a job, and Cherie wants to go back to school. “I can’t wait,” she says.

Herb and Cherie are among the luckier ones. Overall, the fate of Kushel’s participants has varied. At the study’s 18-month mark, fewer than half had managed to escape the streets, some by moving in with relatives or — less ideally — into nursing homes (paid for by Medicaid, or Medi-Cal in California), or, like Herb and Cherie, into affordable housing or permanent supportive housing.

At the other end of the spectrum, Kushel has confirmed 20 deaths among her participants — a figure about five times higher than what would be expected for the same age cohort among the general population. A few more are missing and suspected to be dead, and still others almost certainly face that fate in the near future. When participants fail to show up for their check-ins, Kushel’s colleagues usually account for them by phoning friends and relatives, or, in extreme circumstances, taking to the streets to search for them. “We’re in close touch with several people who have advanced cancer and are living on the street,” Kushel says. “People tell me, ‘I just don’t want to die in my car.’”

Solutions will not come in time to help all of the participants, but Kushel does think they are attainable. First, she says, we must stop the influx of newly homeless. This requires addressing the nationwide crisis of lack of affordable housing, particularly for those 50 and older. It also means coming up with more aggressive measures to prevent evictions, which would, in turn, prevent the onset of homelessness. The price tag for this is not so high: A recent study published in the journal Science found that people in Chicago who were in danger of losing their housing or having their utilities shut off but who also received one-time subsidies of up to $1,500 were 76 percent less likely to wind up in a shelter.

Older adults who are already homeless could best be helped by expanding the availability of permanent supportive housing, Kushel believes, and of finding creative ways to allow them to move in with relatives. That includes ensuring that they obtain benefits they qualify for, like Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income.

Despite the distressing condition of her study subjects and the systems that seem to be stacked against them, Kushel remains hopeful that things will improve. “I actually think we are better than this as a country,” she says. “Perhaps this is naive, but if people realize we are letting 55-year-olds who have worked their whole lives freeze on the streets, then maybe there will be a tipping point.”