A new report highlights the long-term effects of Head Start on non-cognitive skills.

By Dwyer Gunn

First Lady Lady Bird Johnson visits a Head Start class in 1966. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Last year, researchers from Vanderbilt University’s Peabody Research Institute released a paper detailing their evaluation of the state of Tennessee’s pre-K program, focusing specifically on the state’s most disadvantaged four-year-olds. Their results came in contrast to most of the previousevaluations of early childhood education programs, which found impressive long-term results, but focused on very small, high-quality, expensive programs and relied on small sample sizes — the infamous Perry Preschool program, for example, cost over $17,000 (in 2006 dollars) per student.

The Peabody Institute’s evaluation was the first randomized, controlled trial of a large-scale, state-funded, pre-K program. And the results weren’t good. Children who participated in the program exhibited higher test scores at the end of pre-K and were described as “being better prepared for kindergarten work, as having better behaviors related to learning in the classroom and as having more positive peer relations,” the study found. But those effects disappeared entirely by the end of kindergarten; by second grade, the children who had participated in the pre-K program were actually performing worse in school and were rated by teachers as less well-prepared for school, possessing poorer work skills, and harboring more negative feelings toward school.

The study received a lot ofpress and provoked a lot of hand-wringing. In response, James Heckman, the Nobel Prize-winning economist who conducted the Perry Preschool evaluations, counseled patience, pointing out that first-, second-, or third-grade test scores may not be the best metric by which to judge an early childhood education program:

Too often program evaluations are based on standardized achievement tests and IQ measures that do not tell the whole story and poorly predict life outcomes. The Perry Preschool program did not show any positive IQ effects just a few years following the program. Upon decades of follow-ups, however, we continue to see extremely encouraging results along dimensions such as schooling, earnings, reduced involvement in crime and better health. The truly remarkable impacts of Perry were not seen until much later in the lives of participants. Similarly, the most recent Head Start Impact Study seemingly shows parity at third grade while numerous long-term, quasi-experimental studies find Head Start children to attend more years of schooling, earn higher incomes, live healthier, and engage less in criminal behavior. Considering this, it is especially important that we see HSIS through before condemning Head Start.

Heckman, it turns out, may have been on to something.

Earlier this month, the Hamilton Project’s Lauren Bauer and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach released a study on the long-term effects of childhood participation in Head Start, a large, federally funded early childhood education program. Their results resoundingly support Heckman’s arguments. Previous evaluations of the short-term impacts of Head Start have echoed the Tennessee evaluation — short-term boosts in test scores that “fade out” once children finish the program. Longer-term evaluations, meanwhile, have found modest effects of Head Start participation on high school graduation rates and the likelihood that participants will attempt post-secondary education, but haven’t analyzed the effects of the program on participants past the age of 28.

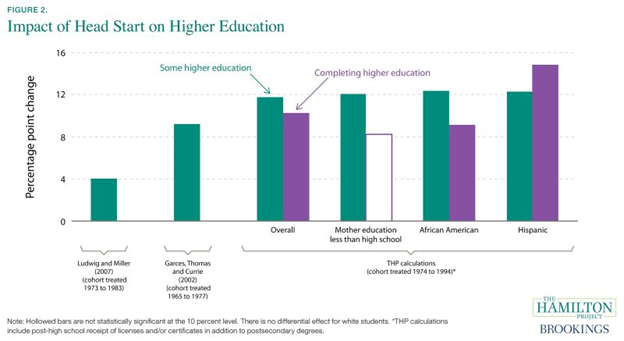

(Chart: Brookings Institution)

Bauer and Schanzenbach’s new study is the first to look at outcomes for both participants who are now older than the age of 28 and for those who more recently went through the program. Their results show that, compared to siblings who either attended a different preschool program or didn’t attend preschool at all, Head Start participants exhibited higher high school graduation rates (more so than in previous evaluations) and were more likely to have completed some kind of higher education credential (including licensures and certification).

Among Hispanics, Head Start participation increased the likelihood of completing some kind of post-secondary credential by approximately 15 percentage points.

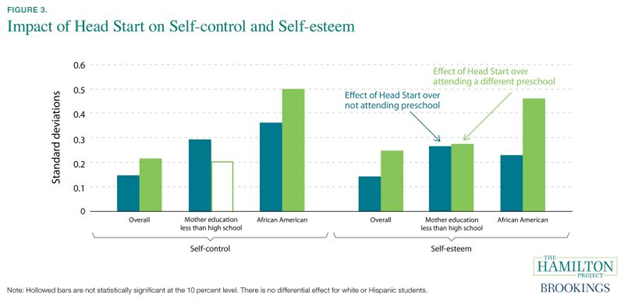

(Chart: Brookings Institution)

Another interesting conclusion in this study concerns the effects of Head Start on non-cognitive traits — self-control and self-esteem. Bauer and Schanzenbach found that Head Start participants exhibited improved self-control (as measured by planning, problem-solving, and behavior-monitoring behaviors) and self-esteem, with particularly dramatic effects for African-American children.

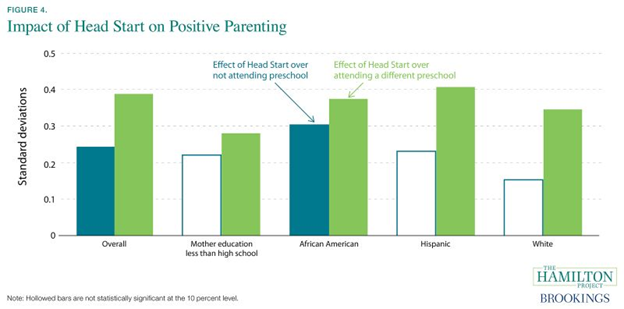

(Chart: Brookings Institution)

What’s more, the legacy of Head Start affects the next generation of children. The researchers found higher rates of “positive parenting practices” (i.e. reading to their children, praising their children, showing physical affection, refraining from spanking, etc.) among Head Start participants.

“There’s something about this program that’s causing these kids to parent differently than their siblings, years after they attend,” Bauer says. “That’s a pretty interesting finding.”

This research should serve as confirmation that it is, in fact, possible to provide effective early childhood education on a large scale. “The Head Start centers are independent, and there’s a wide range of quality within the program,” Bauer says. “So we were really heartened to see Head Start perform better, not just on being at home, performing better than the other preschools.”

Universal pre-K is becoming a bipartisan cause, and it’s crucial that the programs we put in place are high-quality — the research clearly indicates both that early childhood is an enormously important and vulnerable time and that high-quality programs can reduce achievement gaps, while low-quality programs can exacerbate them. But Bauer and Schanzenbach’s work illustrates the importance of evaluating early childhood education programs on more than just short-term test scores. A child’s math scores in first or second grade may not, in fact, be the only indicator of how an early childhood education program has changed them, or might change future generations.

“What we’re seeing in this study is that when you look at the causes of achievement — things like self-control — these are persistent effects,” Bauer says. “Some of the fade-out people talk about, we might not see it as fade-out if we were measuring some of these behavioral outcomes.”