We asked four researchers who study the Affordable Care Act’s public marketplaces.

By Francie Diep

(Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Health-insurance giant Aetna is pulling out of 11 of the 15 states where it currently offers plans under Obamacare marketplaces, the company announced this week.

Aetna claims it’s leaving after incurring too many losses in the marketplace. It says too many marketplace participants are sick and have high health-care expenses, and not enough healthy people are signing up to spread out the risk, USA Today reports. Some analysts have also speculated Aetna is retaliating against the Obama administration for blocking its planned merger with another major insurance company, Humana. The Huffington Post obtained documents in which Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini said if the merger didn’t go through, “it is very likely that we would need to leave the public exchange business entirely.”

This isn’t Obamacare’s first high-profile exit. A few months ago, UnitedHealth Group also ended most of its marketplace plans (though UnitedHealth hadn’t insured as many people under Obamacare as Aetna does). Departures like Aetna’s and UnitedHealth’s are a blow to those who live in areas with few other organizations participating in Obamacare. With little, if any, competition, the remaining companies may raise prices. The government has no contingency plans for counties that end up with one or zero Obamacare insurance providers, Vox reports.

For more, Pacific Standard asked researchers who study the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces about why Aetna left and how to prevent other companies from departing in the future. Here’s who we talked with:

- Daniel Arnold, research associate at the Nicholas C. Petris Center on Health Care Markets and Consumer Welfare.

- Lynn Blewett, director of the State Health Access Data Assistance Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- Peter Cunningham, professor of health behavior and policy at the Virginia Commonwealth University.

- Larry Levitt, senior vice president for special initiatives at the Kaiser Family Foundation.

How many people are actually covered by Obamacare?

LB: It’s small. It’s about 6 percent of the population.

Why is this such a big deal, then?

DA: It’s the segment of the population you want to help the most. These people don’t have jobs, usually are lower income.

Is there evidence to back what Aetna was saying, that companies are struggling because there are too many sick people and not enough healthy people enrolled in Obamacare?

DA: There is some evidence of this. The Department of Health and Human Services contends the risk pool is improving.

LB: It varies from state to state. In states like California and New York, you have a large enough pool to spread the risk. In other states, like here in Minnesota, we only have 300,000 people in our whole individual market. So if you add or subtract 25 percent, which happened [when the law went into effect requiring everyone to buy health insurance], there could be a lot of sick people coming in.

LL: It’s more the brand-name national insurers that tend to have broader networks and higher costs that have difficulty competing. The insurers that are doing well tend to be regional plans or plans that have traditionally served Medicaid. Those plans tend to have narrower networks and lower costs so they can offer lower premiums. People in the marketplace have been tremendously price sensitive.

So what can we do to prevent more companies from leaving Obamacare in the future?

LB: There’s talk about a re-insurance program, where you’d have a lower attachment point, like maybe $30,000 or $40,000, and then you basically buy tax-dollar-supported insurance for those extra costs. If a company knows that all its cases above $40,000 are going to be covered, it can have better control over its estimate of its costs.

PC: In terms of what insurances could do, there is some evidence that an arrangement more like health maintenance organizations, where they have a smaller group of providers — those types of plans seem to be succeeding better than plans that have larger networks of physicians. Of course, the potential flip side to that is that it could cause consumers and patients to have fewer options.

In terms of what could be done to try to improve the marketplaces? I’m not sure the health plans would be in favor [of those solutions]. One example is what they call the public option. You have a plan in the marketplace that is basically a public entity where it’s not trying to get a profit. There would be fewer deductibles, lower co-payments, and lower premiums, which would encourage more people to enroll in the marketplaces.

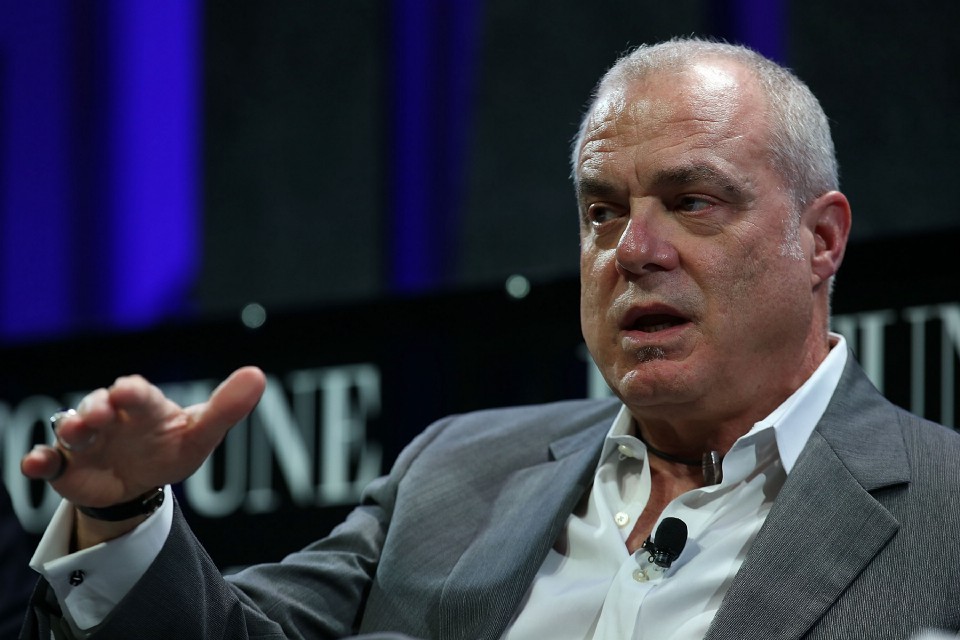

Aetna CEO Mark Bertolini. (Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Another option that the government could consider — and a few states have done this — is to tie participating in other government programs like Medicare Advantage and Medicaid Managed Care to their participation in the marketplace. In other words, if you want to be a Medicare Advantage plan, then you also have to participate in the marketplaces.

One of the early parts of the Affordable Care Act was the provision that allowed young adults up to age 26 to continue on their parents��� health insurance plans, which are usually employer-provisioned plans. One of the unintended consequences is that has limited the available pool of young and healthy people who could enroll in the marketplaces. That provision is popular even among Republicans, so I would expect that is the last thing in the world that would change. I just offer it as another reason why insurers may be having difficulty attracting a younger and healthier patient mix.

What fixes do you think will work best?

LB: I think the re-insurance seems like a reasonable policy solution. It’s been done in state health policy.

DA: Re-insurance is budget neutral. You’re just taking money from insurers that have the healthy enrollees and funneling it to insurers who were unlucky and have less healthy enrollees. That’s the one I’d probably go with.

PC: Ultimately, the issue is getting people to enroll in the marketplaces. That is going to involve a mix of incentives and penalties. The tax penalties are already starting to get pretty substantial. That may become an inducement for people to enroll.

It’s a pretty complicated system. I’m not sure making it more complicated by more regulations is, in the long term, going to be the solution.

||