Presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump is such a child of a man, it’s surprising he doesn’t enjoy more youth support. With his rebellious pose and a promise to shake up Washington, Trump seems calibrated to appeal to angry young voters who aren’t buying the current system. But that’s the problem with guessing how demographic groups will behave based on ahistorical stereotypes about their collective temperament: The kids hate Trump.

A new report from the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University indicates just how badly Trump has performed with voters under 30. Based on exit polls in 21 primary states, Trump underperformed with young voters in every state but New Hampshire. In Maryland, there was a whopping 21 percent gap between his youth and overall support (54 percent vs. 33 percent). He got a third of youth votes in those primaries, 10 points below his share of those 45 and older. And that’s just among Republicans. In an Economist/YouGov poll from late May, Trump’s unfavorables were highest with those under 30 (75 percent). The same survey has 29 percent of likely voters over 65 feeling very favorably toward Trump, while only 9 percent of those under 30 feel that way.

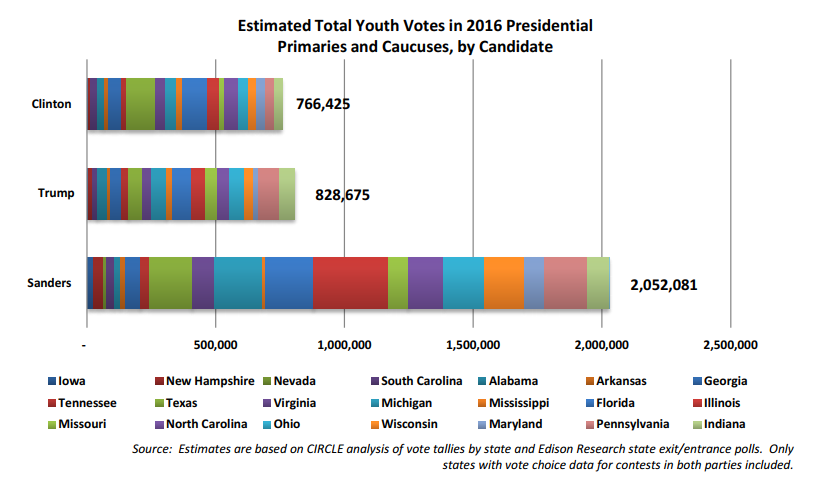

(Chart: CIRCLE)

The Trump campaign has all the youthful vigor of a Cialis advertisement, which is a development New York Times columnist David Brooks predicted in 2007. Brooks wrote then that, based on conversations with his Duke University students, Americans around my age (born in the late 1980s) viewed the Republicans as “the impractical, ideological party.” He saw that a rigid GOP would have trouble attracting young voters, as indeed it has. Unfortunately for Brooks, the rest of his predictions weren’t as good. “If my Duke students are representative,” he wrote, cluelessly, “then the U.S. is about to see a generation that is practical, anti-ideological, modest and centrist (maybe to a fault). That’s probably good news for presidential candidates like Rudy Giuliani and Hillary Clinton, whose main selling point is their nuts-and-bolts ability to get things done.”

Thankfully, Giuliani is probably not coming back, but Clinton has become the presumptive Democratic nominee in spite of young voters, not because of them. From the beginning of the primaries, Senator Bernie Sanders dominated with voters under 30, clearing the 80 percent bar in Iowa and New Hampshire. During those first 21 primaries that CIRCLE counted, Sanders crushed Trump and Clinton among the kids, beating their combined total by almost half-a-million votes. Not only did Millennials fail to support the pragmatic, moderate Clinton — they flocked to arguably the single furthest left national elected official in the country. Sanders isn’t just not-Hillary; he is so far outside the supposed mainstream that, for most of his career, he refused to join the Democratic Party. Young Democrats are so far left that they don’t even want to vote for a Democrat.

The simplest explanation for this ideological turn among the youth is that the generation raised under neoliberalism doesn’t think it’s a good way to run a country or a planet.

The results sent the commentariat spinning: What do Millennials have against Clinton? The Bernie Bro archetype explained a lot: Young men just can’t abide a woman executive and they have seized on the morally righteous Sanders instead. No doubt that’s true for some exceptionally loud Sanders voters, but misogyny alone doesn’t explain Sanders’ Millennial support, which happens to skew toward women. This apparent contradiction yielded some tortured logic from Gloria Steinem, who suggested young women were following young men into the Sanders camp. In response, Elizabeth Bruenig explained in painstaking detail the policy positions that were pulling young women to Sanders. But it’s still not clear that the pundit class understands that differences in generational policy preference aren’t a simple manifestation of emotional insecurities among young adults.

After the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, Vox editor Matt Yglesias tweeted: “The heavy age gradient in Brexit voting really undermines economics-centered accounts of behavior. It’s about values and culture.” Young people in the U.K. had voted to stay, which Yglesias interprets as a sign of cosmopolitan attitudes based on a short life spent in a united Europe. But, like their peers in the U.S., just because young voters aren’t embracing a radical xenophobic program doesn’t mean they want things to stay the same. In his 2015 election as Labor Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn’s support was higher among younger voters than among older voters (around two-thirds, compared to 51 percent of those over 60), and Corbyn, like Sanders, represents a hard-left shift for a party that long ago drifted to the moderate center.

It’s difficult to explain either situation with generational psychologizing. Young people in both countries seem to want fundamental social change, and they want it now. Sanders and Corbyn are both veteran protesters and open socialists; Brooks was way off the mark when he imagined (fantasized?) a generation of hard-core moderates. At the same time, Millennials in both countries have been relatively impervious to the “Burn it down to keep the immigrants out!” libidinal craze that has captured the imaginations of so many of their grandparents.

Still, for some observers, these two kinds of demographically distinct anger (xenophobic old-timers vs. the socialist youth) remain hard to tell apart. At Fusion — a site that’s supposed to know about young people — Felix Salmon opens his piece “Brexit, Hamilton, and the Limits of Democracy” in this way: “All over the world, the voice of the people is rising up and being heard. Sick of being condescended to, voters are kicking out formerly entrenched elite technocrats in acts of anger and frustration. That kind of desire for revolutionary change powered both the Sanders and Trump campaigns; it also resulted in Britain’s seismic vote to leave the EU.” From where Salmon is sitting, all desire for fundamental social change is similarly clueless and unpragmatic.

This false equivalence is an obfuscation for Salmon’s deeper unease. It’s not the methods of Sanders supporters that he objects to (after all, what have they done but vote for a long-serving Senator in a party primary? They didn’t pledge allegiance to a game show host!); it’s their actual beliefs. Most pundits drank the End of History Kool-Aid a long time ago, and they think democratic socialism is itself some kind of knee-jerk hysteria. “You want higher taxes on the rich to pay for a safety net and supply more public services? Calm down, be realistic!” For such pundits, anyone who isn’t an extension of the 1990s Clinton/Blair “Third Way” just sounds like Trump. Their political imaginations are so shriveled they can’t tell the difference between building a wall with Mexico and single-payer health care.

Young voters, on the other hand, clearly can tell the difference between reactionary fantasies about cleansing their countries and the dream of a government that cares most for those who have the least. Anti-capitalism didn’t die with the Soviet Union, even if nations like the U.S. and the U.K. were able to purge almost any politician who wasn’t down with the New World Order. As Peter Frase puts it, Sanders and Corbyn are survivors, and the only eligible leaders to represent the socialist position this time around:

Our political period is characterized by a rising, but still largely disorganized left, arrayed against a moribund but still institutionally powerful neoliberal order that uses its accumulated power to compensate for its complete lack of compelling answers to contemporary political questions. In order to contest state politics at the highest level — the presidency of the United States, the Prime Minister of the U.K. — someone had to be found, within the higher echelons of power, who could serve as a figurehead.

Young people in the U.S. and the U.K. aren’t voting for socialists to make a point to their parents, and neither Sanders nor Corbyn can be plausibly cast as a rock-star messiah or a Trumpish demagogue leading the kids astray. Sanders isn’t charismatic enough to convince his immediate family what to order for takeout. The simplest explanation for this ideological turn is that the generation raised under neoliberalism doesn’t think it’s a very good way to run a country or a planet. There’s no shortage of evidence to support such a position — global warming, pointless war, vicious social inequality, etc. — and voting for a grouchy old socialist is an incredibly moderate, measured response. Characterizing it otherwise is rank hackery.

Come November, a plurality of young American voters won’t have a chance to cast a second ballot against capitalism, and it’s unclear if Corbyn will weather the soft coup underway against his leadership as I write. The “still institutionally powerful neoliberal order” that Frase writes about will probably win this round, but they can’t just call socialists crazy until they go away. Being mad doesn’t make you wrong, and next time they won’t get an old scrub like Sanders.

||