We need people to actively seek the diversity they want.

By Lisa Wade

A 1936 map of Philadelphia showing redlining of lower income neighborhoods. (Photo: Public

Racial segregation in housing is a persistent and pernicious problem in American life. If neighborhoods are filled predominantly by one race or another, that group of people can be advantaged or disadvantaged by virtue of where they live. Decisions about where to put parks, garbage dumps, toxic facilities, airports, and highways, for example, can affect some groups more than others. Some neighborhoods might not have good jobs or public transportation, or sufficient numbers of grocery stores, nursing homes, or recreation facilities, but be filled with check cashing businesses, liquor stores, and cigarette advertising. The quality of schools, water systems, levee systems, and even the air itself varies by neighborhood. And a large and robust literature in sociology shows that good things tend to cluster in whiter neighborhoods and bad things in neighborhoods that are predominantly African American or Latino.

But why are neighborhoods racially segregated? And why do they resist integration?

One possibility is that white people simply prefer to live among others of the same race. What comes to mind perhaps is a white family that sells their house the second a black family moves in next door, but a model developed by economist Thomas Schelling shows that even a surprisingly weak preference will produce systemic segregation.

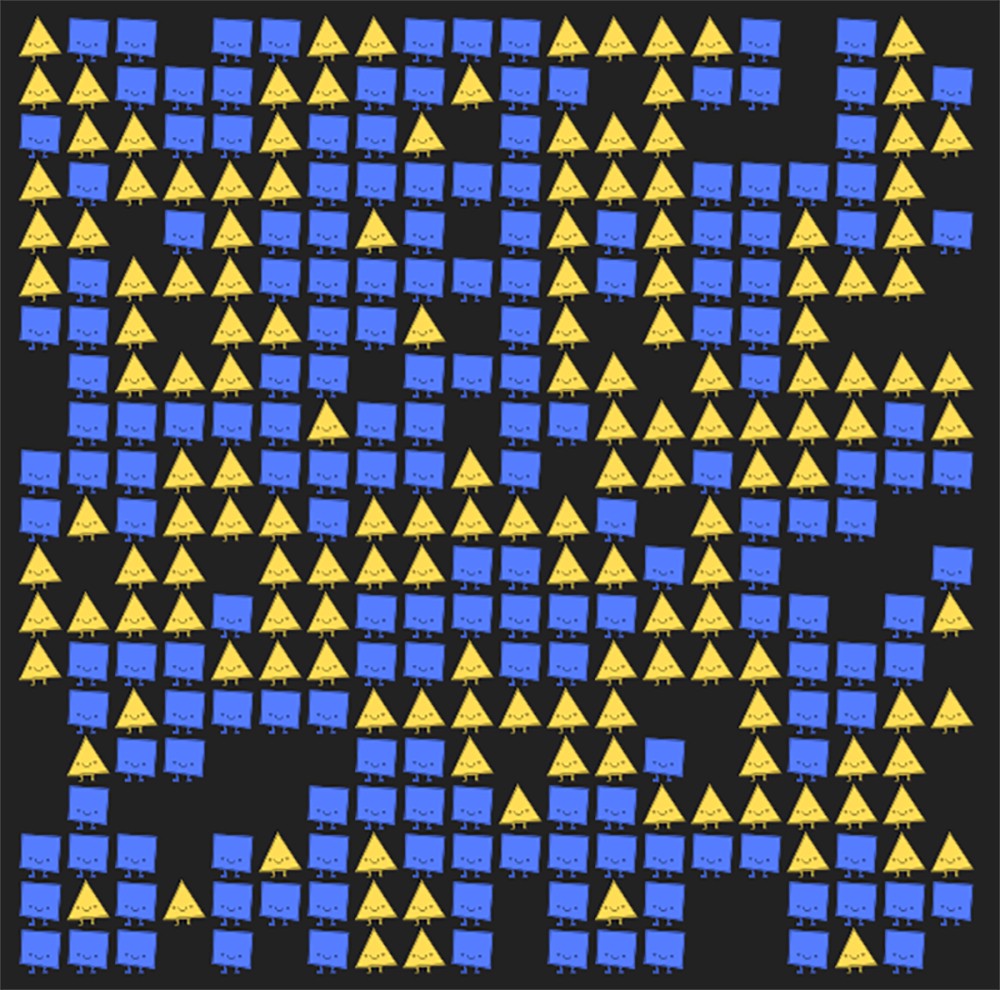

What if, for example, there are two types of people and each are happy in a diverse neighborhood, but they become uncomfortable when fewer than one-third of their neighbors are like them? If you randomly move the uncomfortable households around until everyone’s happy, segregation is mathematically guaranteed. Here is a simulation, at the Parable of the Polygons, of how segregation results from a preference that one-third or more of one’s neighbors are the same race:

Obviously, the more of a preference, the more extreme the segregation, but the lesson is that racially diverse neighborhoods are undermined not only by a strong dislike for living alongside other races, but also a slight preference for being among at least some people of the same race.

Schelling also notes that if, we start with already segregated neighborhoods and we reduce bias, nothing changes at all. Most people who are surrounded by people like themselves won’t move just because they wouldn’t object to being around people who are different than them.

Instead, to substantially reduce residential segregation, people will not only have to accept diversity, they will have to actively reject segregation. And, again, even a weak preference for diversity will do it. In fact, Schelling’s model shows that, if people are comfortable living in neighborhoods in which 90 percent of their neighbors are the same race, but reject 100 percent segregated ones, the result is integration. Here’s what it would look like if people moved out of neighborhoods in which 90 percent of their neighbors were the same race and into more integrated neighborhoods:

The take home message is that, to end residential racial segregation, we don’t need to reduce bias, we need to increase desire. We need people to actively seek the diversity they want.

||

This story originally appeared on Sociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “Rejecting Homogeneity, Not Reducing Bias, Will End Residential Segregation.”