With a patchwork, piecemeal system of civil legal aid, states are a long way from fulfilling the Constitution’s promise of “equal protection under the law.”

By Jared Keller

(Photo: Bruno Vincent/Getty Images)

The Pledge of Allegiance ends with an especially significant guarantee: “liberty and justice for all.” But, according to a new report, states are failing their citizens on the promise of equal justice under the law.

The 2016Justice Index, created by the National Center for Access to Justice at Cardozo Law School, seeks to look beyond just the treatment of citizens by juries and judges, and to instead evaluate how well states ensure that all residents have equal access to the civil legal system in the first place. Administered by 37 attorneys from five law firms, the Index surveyed the chief justice and chief court administrator from every state (plus Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico) and undertook a rigorous examination of each state’s legal policies and practices.

The results are appalling: Despite the Sixth Amendment’s mandate of the right to counsel, there are only 6,953 civil legal aid lawyers in the nation serving people who can’t afford counsel, out of a total sector of 1.3 million lawyers. That means that, for every 10,000 Americans living below 200 percent of the federal poverty line, there’s a meager average of 0.64 civil legal aid attorneys available. And it’s states with particularly high poverty rates like Mississippi, Texas, and South Carolina that have the fewest resources available to those who can’t afford legal help: In some states, as many as two-thirds of the litigants appear without lawyers in matters as important as evictions, foreclosures, and child custody proceedings.

The best and worst states (plus Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C.) for civil legal aid in the U.S. (Source: NCAJ)

“Legal aid programs simply don’t have sufficient resources to represent the people referred to them,” says David Udell, executive director of the NCAJ. “As a result, they turn at least one person away for every person who receives assistance. Consider that number in contrast to the fact that there are 40 attorneys for every 10,000 people in the general populace.”

The lack of attorneys is an entry point into the vast problems of the United States’ legal system.According the the 2016 Justice Index, states aren’t just failing at providing lawyers, but also in making accommodations for disadvantaged Americans. While the high cost of filing fees keeps thousands of Americans from seeking justice, only 12 states require court employees to inform Americans that they can waive their fees. This is particularly troubling when you consider that 48 states have increased criminal and civil court fees since 2010, according to a 2014 investigation by National Public Radio, the Brennan Center for Justice, and the National Center for State Courts. In some cases, the inability to pay court fees can land a citizen an an inescapable limbo behind bars — with potentially deadly consequences.

“Legal aid programs simply don’t have sufficient resources to represent the people referred to them.”

“While all states make available a waiver of filing fees to start or defend a civil action, a far smaller number of states alert court litigants to the availability of waivers,” Udell says. “They don’t put it on their websites. The fact that it’s available doesn’t mean that people get it.”

These obstacles go beyond economic status. Americans for whom English is a second language face a different problem: How can they make the most of the legal system if there’s no clear avenue for understanding the civil law system? Unfortunately, almost 50 percent of states don’t require an interpreter for citizens facing “life-changing” court cases like child custody, domestic violence, or foreclosure. Considering that some 19.2 million working-age American adults are considered to have limited English proficiency, this issue of language access is far more serious and endemic that simply a few broken sentences.

The same issues surface for mental health. A staggering 45 states do not provide dedicated court employees focused solely on helping those with mental disabilities, and 10 don’t recognize the right to counsel in cases of guardianship stemming from mental-health issues.

These issues of access have serious consequences. A study from the Boston Bar Association showed that two-thirds of citizens in eviction cases were able to stave off expulsion with the help of legal counsel; the other third who lacked representation were forced to leave their homes. A report from the Institute for Policy Integrity found that access to an attorney, more than psychiatric counseling or shelters, helped reduce instances of domestic violence by giving victims the avenues to achieve legal independence from their abusers. And data from Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse revealed that almost 90 percent of children involved in immigration proceedings without an attorney ended up leaving the country; only 28 of those with representation suffered the same fate.

“Some of these policies seem dry when considered in the abstract, but they have life or death consequences for people whose lives are at stake in matters that include eviction, foreclosure, domestic violence, debt collection, and so on,” Udell says. “If someone doesn’t understand the language of court proceedings involved in obtaining a protective order to drive off an abuser, of proceedings that will result in an order that will require them to move out of their apartment, their lives can be forever altered for the worse.”

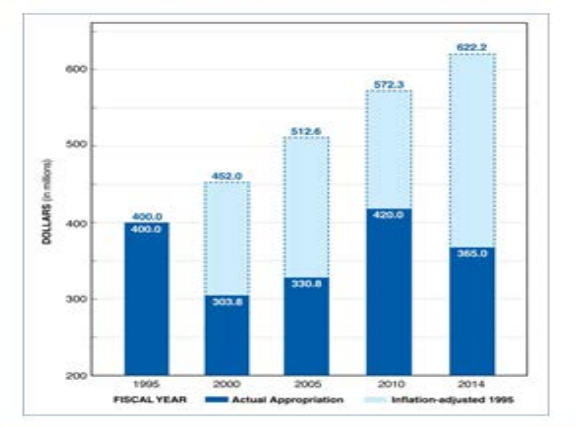

There are a few causes of this crisis. First, funding for the Legal Services Corporation, the federal agency that supports and monitors civil legal aid in the U.S., is meager. According to a 2013 report from the Center for Law and Social Policy, LSC funding “today purchases less than half of what it did in 1980, the time when LSC funding provided what was called ‘minimum access’ or an amount that could support two lawyers for each 10,000 poor people in a geographic area.” This is the result of both inflation and budget reductions that severely hindered the agency in 1982, 1992, and 2012. Between 2010 and 2012 alone, the LSC lost 10.3 percent of its legal aid staff.

LSC appropriations, 1995–2014. (Source: Kansas University School of Law)

While state sources supposedly made up the difference, austerity measures born from the 2008 Great Recession — when coupled with an uptick in civil actions stemming from foreclosures, consumer credit disputes, layoff disputes, and other recession-related conflicts — have left courts without adequate funding. As a result, legal aid attorneys are drowning in cases. It’s worth noting, too, that while federal courts only saw about 271,950 civil filings in 2013, state courts saw a record 102.3 million cases in 2006alone — and that number is rapidly increasing. The result? The U.S. civil aid system “is funded far below the level of funding provided by most of the other Western, developed nations,” given the sheer volume it experiences in a given year, according to CLASP.

Perhaps more importantly, researchers and reformers have suffered from a major lack of data for years, a deficiency that makes evaluating and attacking the problem of civil legal aid difficult. “If you want to know the data for your fantasy baseball team, you can know it up to the last swing from the game that aired this evening,” Udell says. “But if you want to know how many cases are in the state courts, you have to look at data that’s years old. And if you want to know how many of those plaintiffs don’t have the right kind of legal representation, you basically have to forget about it.”

This is part of the goal of the Justice Index in the first place: to not only articulate the borders and boundaries of America’s sub-par legal aid system, but to map out the realistic initiatives undertaken by courts that could be replicated in other states without additional budget outlays. After all, it’s a thorough understanding of state-level data that will increase opportunities for taxpayers “to advance their interests and enforce their rights in their state justice system,” as Udell says.

“We have to make it easy to identify for each state a set of changes which should be on its reform agenda to make the courts more able to deliver on the promise of equal justice that is contained in the Pledge of Allegiance.”

||