Low-income students struggle to finish college. A new paper suggests that a combination of financial and non-financial supports can help.

By Dwyer Gunn

University of California-Berkeley students walk through campus. (Photo: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

College affordability is a hot topic this campaign season. Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have sparred frequently over the best way to make college accessible for low- and middle-income families. Both candidates, despite their differences in ideology, believe an overhaul is in order. Sanders’ plan calls for free college tuition at all public universities and colleges. Clinton’s plan relies on “debt-free” tuition at public colleges and universities and free tuition at community colleges. Even Donald Trump, not someone who’s known for his empathy, has advocated “some governmental program” to help low-income students pay for college.

Most of these conversations have focused purely on the financial challenges low-income students face, but a working paper released earlier this week by the National Bureau of Economic Research highlights the important role that non-financial supports play in ensuring that low-income students finish their degrees. The paper, by Charles Clotfelter, Helen Ladd, and Steven Hemelt, found that a program providing financial and non-financial support to low-income students in North Carolina increased graduation rates and academic performance.

Right now, America faces a difficult reality: High-paying jobs for high school graduates are drying up and the wage premium accorded to college graduates is higher than ever, but the cost of higher education has skyrocketed in recent years. Americans currently owe $1.3 trillion in student loans, seven million borrowers are in default, and still more are behind on their student loan payments. These trends are particularly painful given the stagnating wages of many lower- and middle-income Americans.

There’s a growing recognition at many schools that low-income students might need more than just money to succeed in college.

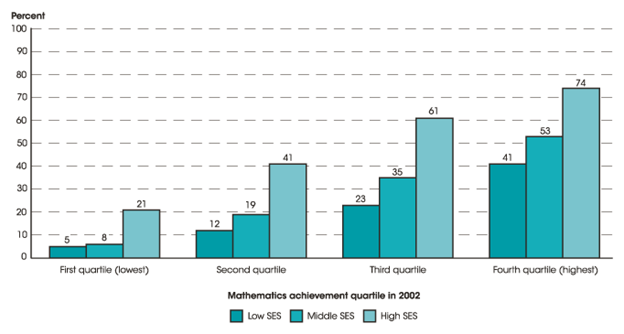

Making college more affordable is an important goal, but it’s only part of the battle for low-income students. There are substantial college completion gaps for low-income and minority students. Last year, the National Center for Education Statistics released a report on the educational outcomes of a group of high school sophomores that the researchers first began tracking in 2002. Comparing the educational outcomes of kids with similar high school math test scores, the researchers found that lower-socioeconomic status kids were much less likely to have earned a bachelor’s degree by 2012 than middle-socioeconomic status students, and middle-socioeconomic status students were, in turn, less likely to have earned a degree than higher-socioeconomic status kids.

This chart, from the report, illustrates their findings:

The percentage of spring 2002 high school sophomores who earned a bachelor’s degree or higher by 2012, by socioeconomic status and mathematics achievement quartile in 2002. (Chart: U.S. Department of Education/National Center for Education Statistics/Education Longitudinal Study of 2002)

Low-income students who enroll in, but don’t finish, college are at a particularly high risk of defaulting on their student loans. Contrary to the popular media narrative, it’s not graduates of elite private schools with medical or law degrees who struggle the most with their student loans — it’s people who have borrowed small amounts of money for degrees they never finished. According to a report released last year by Demos, approximately 39 percent of black borrowers and 38 percent of low-income borrowers drop out of college, compared to only 29 percent of white borrowers and less than 25 percent of high-income borrowers. (These numbers are much higher at for-profit four-year and for-profit two- or fewer-than-two-year institutions.)

“In a way, student debt would be a less worrisome issue if all students who entered college were essentially guaranteed to receive that credential, and that their degree always provided a labor market boost,” the Demos report concludes. “Unfortunately, neither of those are the case. In fact, only 56 percent of degree-seeking students complete college within six years.”

While free tuition would go a long way toward closing the completion gap — many low-income and minority students cite financial problems as their biggest reason for dropping out — there’s also a growing recognition at many schools that low-income students might need more than just money to succeed in college. In 2003, the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill decided to tackle this problem with the program that’s the subject of the new NBER report: Carolina Covenant.

The program provides low-income students with loan-free financial aid packages (consisting primarily of grants and work-study awards) sufficient to meet 100 percent of a student’s demonstrated financial need. (The program also provided eligible students with a variety of supplemental services.) The school has increased its services over time, but the crux is still the same: Covenant scholars have access to “mentoring by a faculty or staff member, peer mentoring by older Covenant scholars, academic workshops on topics such as time management, note taking, and subject-specific study techniques, career and personal development opportunities such as career workshops, financial literacy, an ‘etiquette dinner,’ and social events.”

In their recently released paper, the researchers found that the Carolina Covenant program increased graduation rates by about eight percentage points among students eligible for the full program. That’s not a trivial finding. The average student eligible for the Covenant program had a family income of approximately $26,000 — an 8 percent increase in college graduation rates for those students means they’re graduating at approximately the same rate as students from families with incomes of $125,000.

After conducting a back-of-the-envelope cost-benefit analysis, the researchers concluded that the benefits of the program (which stem from the higher earnings of college graduates) outweigh the costs within two years of graduation.

“[O]ur findings are consistent with the notion that expansions of need-based aid for low-income, high-ability students stand the best chance of affecting postsecondary outcomes such as graduation when coupled with strong non-financial supports,” the authors concluded.

Notwithstanding the many challenges facing the American economy today, post-secondary education is still the best route to a higher income and a better life, and making college more affordable for low-income students is vitally important to the health and future of our economy. But policies to make college accessible to more Americans shouldn’t ignore the fact that many low-income students need more than just free tuition or debt-free tuition to succeed at college.

||