Thirty years after the nuclear disaster, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone remains a ghost town — but recently it’s seen a boom in “dark tourism.” Why do we visit monstrous sites? The need to acknowledge, and perhaps even experience, our own destructive power.

By Hannah Gais & Eugene Steinberg

A checkpoint at the entry to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. (Photo: Eugene Steinberg)

No matter who you talk to about Chernobyl, they all want to philosophize.

— Sergei Sobolev, Voices From Chernobyl

Were it not for the sobering booklets about nuclear disaster stacked on a counter, the Kiev office of SoloEast could reasonably be mistaken for a dentist’s waiting room. It is coated in baby blue wallpaper and lit with bright fluorescents. The registration process is quick. For 120 American dollars each and a copy of our passports, we are signed up for a tour the following Saturday.

A week later, we join a group of a dozen other foreigners wearing bright yellow wristbands and pile into a minibus. It’s an ominously gray September morning, which feels appropriate for a trip to Ukraine’s darkest and weirdest tourist attraction, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

The Chernobyl disaster began 30 years ago today, on April 26, 1986, at 1:23 a.m., when reactor number four of the nuclear power plant exploded during a routine systems test. A stream of radioactive vapor spat uranium and graphite pieces around the plant; a fire shot into the sky. The plume was charged with radioactive particles, and its smoke spread radiation over nearly all of Central and Western Europe. The amount of radioactive material released from the burning plant would total 400 times that of the Hiroshima bombing.

Firefighters rushed to the scene, oblivious or indifferent to the risks of radiation. Over a period of two weeks, more than 5,000 tons of sand, lead, clay, and neutron-absorbing boric acid were dumped from helicopters overhead in order to contain the fire. According to the official Soviet count, two died in the explosion and 29 died immediately from acute radiation poisoning in the firefight. Because the illnesses caused by radiation damage are often stochastic, experts have struggled to estimate the disaster’s total death toll. Conservative estimates postulate that the final death toll could be upwards of 4,000. The true extent will likely remain unknown for generations.

“Chernobyl is not a historical place. … It is a sleeping lion. And when the lion is sleeping, you don’t open the cage.”

Aside from power plant, the worst of the radiation fell on the city of Pripyat, then just a 16-year-old Soviet city-of-the-future built for the express purpose of servicing the power station two miles away. The week of the explosion, Pripyat had been preparing for the annual May Day celebrations and the opening of a new amusement park with a Ferris wheel. Its nearly 50,000 inhabitants, unaware of the explosion, rose the morning of April 26 and went about their days. It would take more than 30 hours for authorities to issue evacuation orders. Finally, on April 27, civilians were given two hours to gather their belongings onto buses for “temporary” evacuation. Three hundred fifty thousand people were eventually relocated from the surrounding regions. Then, the Soviet authorities announced the creation of a 1,000-square-mile Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Pripyat became a ghost town.

Except the Chernobyl region was never truly abandoned. In the months after the explosion, tens of thousands of “liquidators” — Soviet volunteers — were brought in from around the Soviet Union to help decontaminate the area. A massive steel sarcophagus was constructed over the ruins of the plant, and villages were bulldozed and literally buried underground. Later, with the fall of the Soviet Union, budget cutbacks created major lapses in the security of the zone. Waves of travelers and looters returned in the 1990s for items left behind. Some elderly residents even returned to illegally live in their old homes. Ukrainian kids from the surrounding areas would dare each other to sneak into the zone late at night.

The Ukrainian government took note of the increased interest in Chernobyl. In 1995, it founded the Chernobyl InterInform Agency, dedicated to Chernobyl education and tours. Though no longer active today, its mission was to increase awareness of nuclear risks. By the end of the decade, a few private Chernobyl tour companies had sprung up to work in partnership with the government. But it wasn’t until the 2000s that formal tours came into high demand.

A mural near the Duga Radar. (Photo: Eugene Steinberg)

Today, the standard day-trip package includes a bus ride from Kiev, a brief stop near the power plant itself, and several guided tours of abandoned nurseries, stadiums, schools, and residential buildings in Pripyat and other nearby villages. Some tours also stop at the 500-foot-tall Russian Woodpecker — a hulking, rusting military radar tower that visitors can climb at their own risk. The price also includes a meal at the Chernobyl canteen. The time for unsupervised exploration is strictly limited.

Chernobyl’s appeal isn’t universal, nor is everyone thrilled by the zone’s touristic appeal. “The name Chernobyl is better known than Kiev, or Ukraine itself,” Iryna Gagarina, then the executive director of the Ukrainian tourist board, told the Guardian in 2004. “Chernobyl is not a historical place. … It is a sleeping lion. And when the lion is sleeping, you don’t open the cage.” For many in Ukraine, Belarus, and other parts of the former Soviet Union, travel to the zone has little, if any, appeal. The trauma caused by the explosion is still raw in these societies, and, for those who lived through the disaster, visiting the zone can be like re-opening a deep wound.

Even the Ukrainian government’s enthusiasm for Chernobyl tourism has fluctuated. Although restrictions on visiting the exclusion zone have gradually eased, in 2011 the government briefly banned all recreational tourism to the area, citing concerns over the potential health effects on tourists and misuse of the profits from these tours. Later that year, a court found in favor of the Emergency Ministry — the body responsible for overseeing tourism to the zone — and the government reversed its decision. The real total is hard to find, but most tour guides estimate the number of visitors who come to the zone through legal channels to be over 10,000 a year.

What makes the rationale behind travel to a sinister place, like Chernobyl, different from, say, the impulse to visit a history museum? Tourism experts posit a number of theories. For one, there’s the sequestration of death in modern society — what’s broadly known as “death denial.” Sociologists identify a few major trends and characteristics to explain why tourists may visit these sites. A host of modern developments have made it harder for us to experience actual horror in the face of death: These include the medicalization of death; the professionalization of the industries associated with death; the secularization in the rituals and language associated with death and dying; the distancing of sites, such as graveyards, from cities and urban areas; and the introduction of an industrial approach to dealing with remains and burials. At the same time, death is still a part of everyone’s lives: We all have to go sometime.

Philip Stone and Richard Sharpley, both researchers at the Institute for Dark Tourism Research in the United Kingdom, think that this paradox is one of the foremost drivers behind interest in dark tourist cites. They write in TheAnnals of Tourism Research that so-called “Dark Tourism,” to places like Chernobyl, “allows the re-conceptualization of death and mortality into forms that stimulate something other than primordial terror and dread.” As our travel to dark tourism sites is always temporary — most tours to the exclusion zone are day trips — it allows one an easy exit to the “real world” whenever staring into the abyss becomes too much to handle.

The trauma caused by the explosion is still raw in these societies, and, for those who lived through the disaster, visiting the zone can be like re-opening a deep wound.

By opening the exclusion zone to tourists, Chernobyl has become a place that, in Stone’s words, “allows for the potential re-sequencing and re-construction of the past.” Guides choose what information to present to the tourists that accompany them, thereby popularizing a singular narrative. Meanwhile, tourists introduce their own experiences with the zone into the stories that they pass along to families and friends. While the exclusion zone is shuttered off from the rest of Ukrainian society by a series of policy measures and some rather porous fences, the touristification of the region signifies its transition from a space of destruction to a space with a particular ritualistic purpose.

Now, Kiev’s Chernobyl Museum feels and looks like an off-beat holy site. An iconostasis framed with barbed wire and radiation warning signs greets visitors as they walk up the stairs. Its doors open onto a display of children’s toys, as well as artifacts from emergency management personnel who handled the containment and evacuation process.

Abandoned gas masks in Pripyat. (Photo: Eugene Steinberg)

Chernobyl’s macabre appeal is also political: It is both a victim and a killer of Soviet communism. The casualties of the disaster weren’t just victims of the regime’s mismanagement and incompetence — they also partially inspired the reforms that would bring down the Soviet Union. The same culture of secrecy that delayed the government from adequately responding to the crisis provoked enough backlash to empower Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s to begin pushing Glasnost, the policy of openness that would eventually contribute to the Soviet Union’s dissolution. The ubiquitous hammer-and-sickle crests and Lenin portraits around the site are not just curious anachronisms, but the ghosts of this defeated state and ideology. In today’s Ukraine, whether this political death is mourned or celebrated is a deeply divisive question.

For Westerners and others further removed from regional politics, the Chernobyl experience is an opportunity to look back in time and through the Iron Curtain, and perhaps indulge in some feelings of Cold War superiority. In an email, Richard Morten, an associate researcher with the Institute for Dark Tourism Research — himself a dark tourism aficionado who has visited and written about the exclusion zone — explains that, even if Chernobyl was not an accurate representation of a Soviet or post-Soviet city, it was “perhaps the most symbolic landscape in representing Western narratives of Soviet social oppression, and the perceived doom awaiting such flawed political ideologies.”

In its exposé on tourism to the region, CNN refers to the zone as a “snapshot of Eastern Europe before the fall of the Iron Curtain.” The 2012 film Chernobyl Diaries presents Pripyat as a city trapped in 1986. “Factories. Schools. Stores. Homes. Apartments. Everything’s still there!” cries one of the characters while trying to sell a visit to Pripyat to his friends. Even a 2011 report from the Telegraph describes the scene from Pripyat in an oddly romantic fashion: “Hundreds of discarded gas masks litter the floor of the school canteen, Soviet propaganda continues to hang on classroom walls, and children’s dolls are scattered about, left where their young owners dropped them in a hurry a quarter of a century ago.”

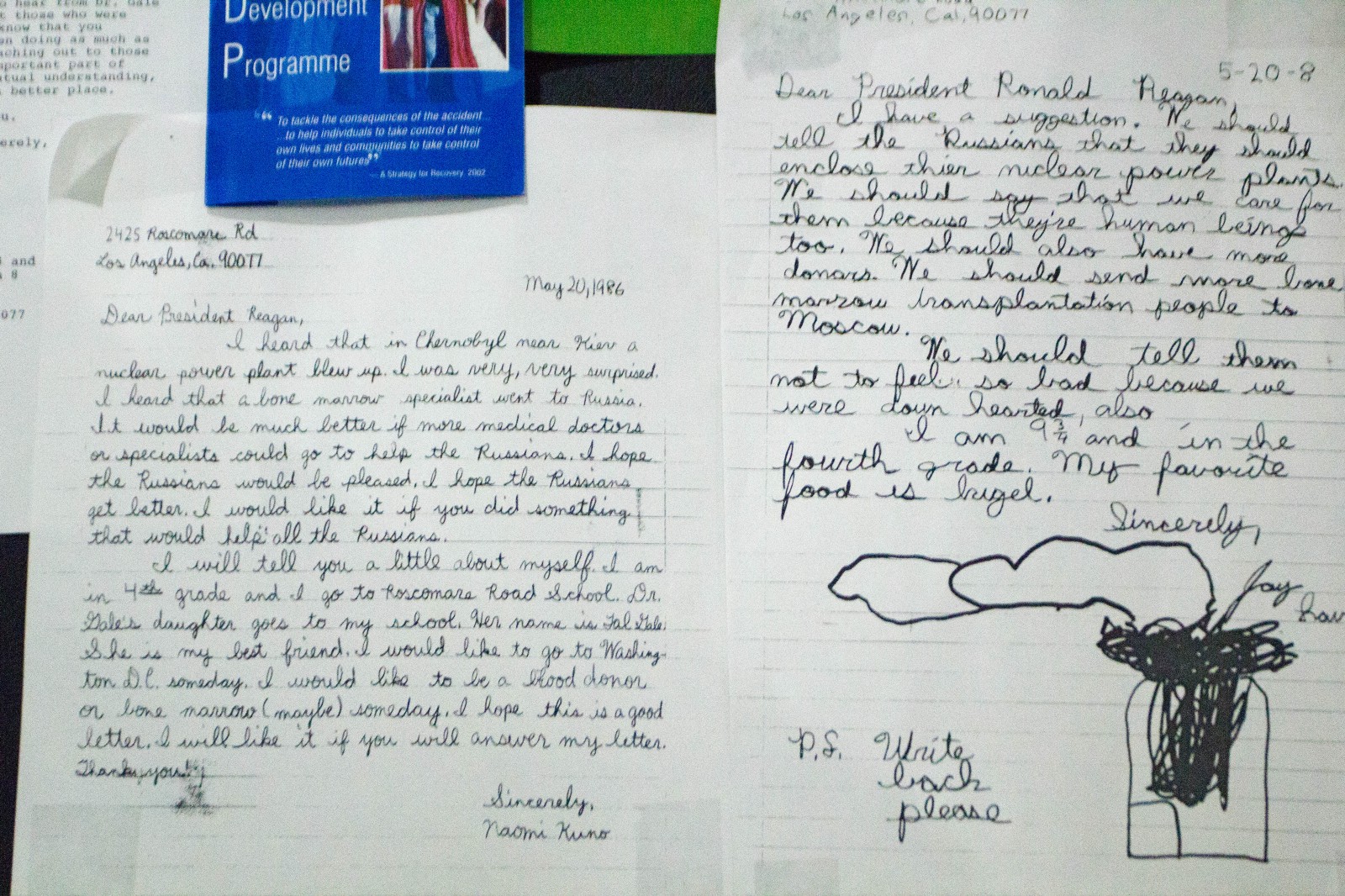

A young girl’s letter to Ronald Reagan, May 20, 1986; Ukrainian National Chornobyl Museum, Kiev. (Photo: Hannah Gais)

Pripyat, in particular, embodies this idea of authenticity. The town is mostly abandoned and appears to be largely unkempt. Bumper cars in the town’s amusement park, which was set to open just five days after the accident in 1986, are overcome by weeds. A couple of hundred meters away, a Ferris wheel sits unmanned and unmoved, its control room filled with broken glass. The city’s heartbreaking beauty gives the disaster a picturesque quality: The gas masks, papers, books, and toys in the abandoned schools, stores, and homes in the area are arranged as if by design.

For those seeking the full “back to the USSR” experience, the site’s identification with death and destruction is of the utmost importance. Presumably, then, it should follow that the site’s overall integrity — namely the fact that is has been untouched, that those dolls on the ground are left exactly where the fleeing children left them — is critical to their dark tourism experience. Still, a tourist who visits the exclusion zone is not merely observing the product of the 1986 accident, but also the residue from a decade’s worth of looting and vandalizing, as well as the minor changes made by tourists in search of an experience that can stand up to their own expectations.

In reality, Pripyat is hardly untouched. Graffiti is conspicuous and far too fresh to be from 1986. But it’s easy to find the perfect shot. Snap a photograph besides the iconic pile of discarded gas masks on the floor of the school’s canteen. Walk among the dolls and toys that litter the floors, propped up alongside piles of schoolwork.

(Photo: Hannah Gais)

It’s hard to go through the experience without feeling as if you’re in a haven manufactured by and for photographers. Other visitors shared a similar sentiment. “Our guides would lead us into a school … push open a door onto a room where several dozen gas masks hung suspended from the ceiling on wires; and then they would retreat, throwing smug, knowing looks to one another as the cameras came out, and photographers started jostling for position,” writes Darmon Richter at the Bohemian Blog.

In a way, this is inevitable. Tourism is intrusive, and a tourist’s experience is, quintessentially, an artificial one. Tourists are led around the zone by guides, who inevitably frame the experience in a manner according to their own political and cultural experiences. Even those, like our 23-year-old guide, who try to make a tourist’s encounter with the zone as “real” as possible, inject themselves into the experience by choosing what information to present and what to ignore. Such a curated approach limits the tourist’s ability to understand and interpret the disaster in a broader or more complex political and historical context.

Maybe this is why the images that have attracted tourists to the region aren’t, first and foremost, those of individual suffering. After all, it’s the crisis’ aftermath that dominates our imagination; in Chernobyl itself, with the exception of one small monument personally erected by survivors and their relatives, the only visible grave markers of the tragedy in the exclusion zone are individual wooden crosses that stand for entire abandoned villages.

As a result, Chernobyl can — at least from a distance — feel like a tragedy without a human face. What’s most personal about the exclusion zone is how empty it is; how many signs there are of the people who used to be here and now are not. Here, it’s the weight of absence that humanizes the crisis.

||