Ten years ago was a great time to grow up if you were addicted to cartoons, but not if you were gay. In the 1990s and aughts, Hey Arnold!, the Magic School Bus, and the Little Mermaid (which featured a deaf Latina mermaid) led the charge to make cartoons more ethnically diverse. WB’s Batman: The Animated Series and Nickelodeon’s As Told by Ginger tackled emotional, heavy topics like peer pressure and neglectful parents that diversified subject matter and emotional impact. The Proud Family and Kim Possible depicted romantic relationships with narratives that took mature approaches to dating, crushes, and holding hands. And yet: As progressive and illuminating as the cartoons of the era were, networks like Cartoon Network and Nickelodeon fell short in a major way—almost universally, they failed to represent queer people.

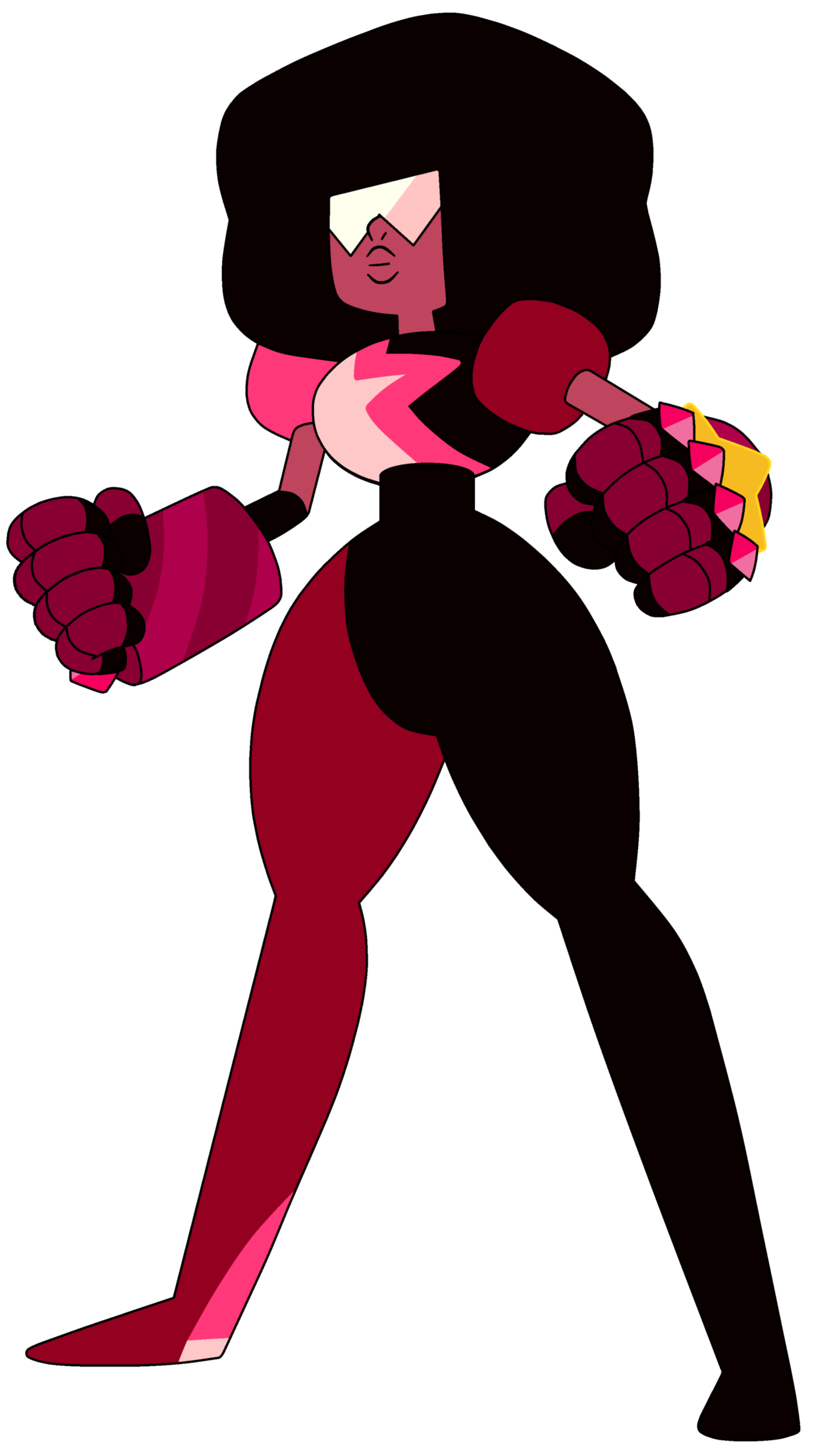

That changed in November 2013, when Cartoon Network first premiered the series Steven Universe. A coming-of-age story about a young boy and his adventures with three women called the Crystal Gems, Steven Universe combines old-school sci-fi with progressive social mores. The show’s Crystal Gems possess the power to fuse together to create a single, more powerful version of themselves. One year in, the show revealed that one of these fusions is between two girls who love each other so deeply that they can’t bear to be apart. With the birth of that character—Garnet, voiced by R&B singer Estelle—Steven Universe became the first mainstream American children’s cartoon on a broadcast network to feature a recurring, openly gay character.

Like many viewers, I was enthralled by the plot twist. On an aesthetic level, the episode that sees Ruby and Sapphire reunite after a long separation—which sees them running toward one another, hugging and kissing—was powerfully and emotionally constructed. But there was another element to my appreciation too: Their relationship was the kind that sixth grade me, anxious, reserved, and gay, would have done anything to see. Queer kids have waited a long time to be represented on broadcast television—something that exceptional shows like Steven Universe, and select cartoons that have followed it, are aiming to change.

In 2015, it’s finally safe to say children’s cartoons are representing the LGBTQ community. Since that groundbreaking episode of Steven Universe, Cartoon Network has added a second lesbian couple to the show, as well as a recurring gay couple to the adventure series Clarence. On Nickelodeon, the Legend of Korra’s titular Korra walked off into the sunset with her female friend Asami in the show’s series finale (the show’s creators later confirmed the two are, indeed, a couple). In children’s films, ParaNorman made headlines for revealing one of its lead characters was gay, and How to Train Your Dragon 2 included a closet-bursting line that flew over many viewers’ heads. That these last two references were minor didn’t make them any less controversial.

Parents’ groups are known to raise hell when gay characters appear on children’s entertainment for fear that homosexuality is too adult. But the introduction of explicitly gay characters is especially notable considering the long history of sexually conservative stereotypes in children’s cartoons. Take Disney’s the Lion King and Aladdin, in which the villains Scar and Jafar present stereotypical depictions of gay men, with feminine qualities and campy behaviors that perpetuate the pop-cultural trope that feminine men have evil tendencies. Or the Little Mermaid, whose villain, Ursula, was inspired by the famous drag queen, Divine. On Cartoon Network, the Powerpuff Girls introduced a creepy drag queen-like villain known as Him, the Buffalo Gals in Cow and Chicken literally “munch[ed] carpet,” playing on a derogatory term for lesbianism, and the Silver Spooner in Dexter’s Laboratory flamboyantly glided across space and performed his lines with a feminine lisp (the episode featuring Spooner was banned from the network.) It’s become a cartoon paradigm for LGBTQ characters to be pigeonholed into one of several types: gay men as villains; lesbian women as steamy seductresses; and transgender people as manipulative and psychologically unstable people.

For LGBTQ youth watching these portrayals, these stereotypes aren’t just offensive, they are explicitly harmful to their mental and physical well-being. Negative stereotyping and prejudiced mindsets can be psychologically damaging, according to research by University of Wisconsin–Madison’s William T.L. Cox. His integrationist study in 2012 found that negative stereotypes and prejudice are a high contributor to bullying, harassment, depression, and suicide. And while adult shows like Modern Family, Glee, and the Fosters now offer an array of queer characters that would have been unthinkable a decade ago, their absence on children’s shows has left television’s most vulnerable viewers without support. Queer adolescents between the ages of 10 and 24 are already four times more likely to attempt suicide than their straight peers and four to six times more likely to cause themselves bodily harm.

When children watch entertainment that tells them that people like themselves are non-heroic, marginal, or villainous, they begin to feel that maybe the TV’s right.

Research on children’s programs, too, suggests that most networks are failing viewers who are not heterosexual white boys. In 2012, two professors at Indiana University studying the relationship between children’s television and self-esteem found that more TV time predicted a drop in self-esteem among all children except white boys. The researchers offered three possible explanations for this phenomenon—one, that television reinforces gender-role and racial stereotypes; the second, that non-white, male children might be using these negative portrayals as a basis for their self-esteem. The upshot? When children watch entertainment that tells them that people like themselves are non-heroic, marginal, or villainous, they begin to feel that maybe the TV’s right.

I know firsthand what it feels like to need positive queer role models. I began seeking out LGBTQ characters in secret at home in seventh grade, when I developed the habit of plugging my headphones into the television and sitting way too close to the screen with the door locked. This was in 2005, when the only shows featuring queer characters were adult or sexually explicit—my choices were pretty much Queer as Folk, Will & Grace, or actual pornography. Watching explicit sex acts confused me: I just wanted simple handholding and couples, the stuff I saw on Disney Channel but with boys and boys and girls and girls. I started to imagine I was going to be a provocative, inherently sexual individual when I grew up.

What if Steven Universe had premiered in the mid-aughts? It would have made a difference for me—but also, probably, for many others. Children’s cartoons are a child’s go-to for nearly everything. They coat backpacks and clothing; their likenesses are molded into dolls and action figurines; they create some of our fondest childhood memories. Cartoons aren’t simply television programs; they are icons that withstand time.

Historically, creators who write queer characters into kids’ shows have been stymied by American studios and broadcast networks. You don’t have to look far back to find examples: In 2000, the Japanese program Sailor Moon S was censored before its North American premiere on Cartoon Network (dialogue that implied Sailors Uranus and Neptune were a same-sex couple was altered to portray the two lead protagonists as cousins instead; Hulu is now streaming the series with original dialogue intact). None of the episodes of the Canadian series 6Teen that feature minor recurring gay characters, which originally aired between 2005 and 2008, are currently available on Netflix (they appear to have never run in the U.S.) In 2014, the Disney Channel series Gravity Falls storyboarded an episode with one scene featuring a lesbian couple—but by the episode’s release, the homosexual couple had become heterosexual. (This was particularly confounding because Disney Channel had included a lesbian couple in their live-action series Good Luck Charlie just a year earlier.)

These days, some creators tread a conservative middle ground by announcing that their characters are gay off-air. In 2014, Olivia Olson, the voice of Marceline the Vampire Queen on Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time, revealed at a book signing that Marceline had, at one point, dated Princess Bubblegum. (According to the show’s creator, Pendleton Ward, Cartoon Network nixed that detail because the show airs in countries where homosexuality is punishable by death.) Craig Bartlett, creator of Hey Arnold!, has allegedly told fans that the character Mr. Simmons, Arnold’s school teacher, is gay, and Eugene, a fellow fourth grader, is proto-gay—a term for a gay kid who hasn’t come to terms with it yet. These facts would likely not have struck younger viewers during the shows’ runs: In both cases, the characters’ true identities were hardly suggested aside from, say, the stereotype in Hey Arnold! that Simmons and Eugene enjoyed musical theatre.

In 2015, kids shouldn’t have to read between the lines. “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was repealed four years ago, and this year same-sex marriages became legal in all 50 states. To simply suggest, onscreen or off, that cartoon characters might like members of their own sex, represents a step backwards for kids’ networks. Being coy about queer characters, after all, isn’t so different than “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”: Both tactics pledge openness to homosexuality but result in silence and stigma. For entertainment aimed at the next generation, that silence simply isn’t good enough.

Children often come to consider their queerness at a relatively early age, though some, like myself, don’t come out for years because they are afraid. We often think of real-world factors when we consider what queer people might have to fear: hate crimes, bullying, and neglect at school or from one’s own parents. But fear can result, too, from what networks choose to show us on TV. At a young age, I thought I would be killed like Matthew Shepard, one of the only gay people I had ever heard of. The source of my anxiety? A Lifetime Original Movie I stayed up too late to watch.

Movies, shows, and books can be hazardous to young people; they can also be a saving grace. Entertainment provides a small relief for those who experience bullying, feelings of isolation, and problems at home. And where children feel as if they belong, they don’t have to be so afraid. Now, it still feels so new to see people like myself on mainstream television: The first time I saw ParaNorman, I was nearly brought to tears though the character’s queerness manifested itself in a single comedic line. But there’s also something nostalgic about these cartoons: When I watch episodes of a series like Steven Universe or Clarence that show me characters I never thought I’d see in my lifetime, it’s like I’m 12 again, re-living the childhood I wasn’t allowed to have.