Seventy-seven years ago, my grandmother left her fourth-floor apartment in Munich carrying a painting by Otto Stein, a modestly popular German artist. Earlier that month, the Nazis had launched a nationwide pogrom against Germany’s Jewish minority, a rampage in which gangs of men burned stores, schools, and synagogues. In the aftermath of what became known as Kristallnacht, the Gestapo rounded up hundreds of Jewish men and sent them to the Dachau concentration camp. Among them was my grandfather, Jakob Engelberg.

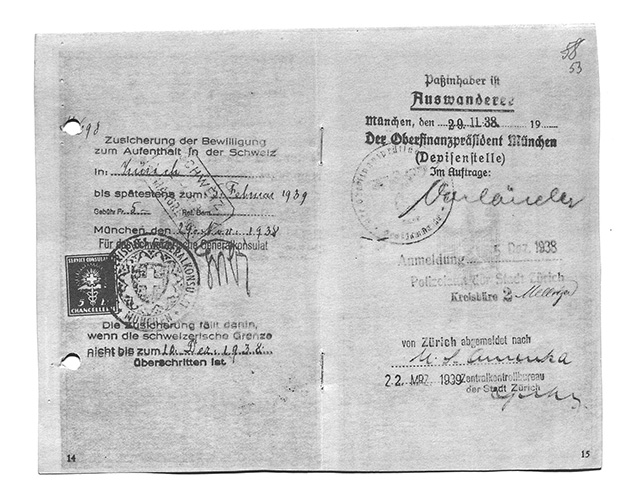

Paula Engelberg never talked about what happened during her visit to the Swiss consulate. But when she returned home a few hours later, she no longer had the painting. What she had was the most precious of commodities in Nazi Germany of 1938: A valid visa to enter Switzerland.

The consulate issued only 600 such documents that year, up from just 200 the previous year. This particular one secured the release of my grandfather from Dachau after two weeks, allowing my grandparents, father, and aunt to escape Germany and ultimately settle in the United States. It made possible the existence of 20 more human beings.

I’m one of them.

Five years ago, I told this story to Christian Salewski, a German journalist who was working at ProPublica for several months as part of a fellowship. I said I had always wondered what had happened to the painting, not because it was particularly valuable—works by Stein can be found on eBay selling for a few hundred dollars—but because I wanted to know its story.

As a journalist, I imagined any number of possible narratives. Perhaps the painting was given to a diplomat who dispensed visas to desperate Jews, a Schindler of the Swiss diplomatic service. Perhaps it had been sold to an art dealer to raise the money for a bribe. Maybe it was simply a gratuity for a service rendered.

I had fantasies of finding a house full of paintings in Switzerland, the owners unaware of the lives saved by their existence.

I told Christian that we had only one real clue. My family had managed to leave Germany with a second painting by Stein, a portrait of a young woman whose gaze seems to follow you, Mona Lisa-like, across a room. In my father’s memory, this painting, which he called “My Mona Lisa,” bore a striking resemblance to its missing sister in both style and subject. The remaining painting hung in our family’s living room, a testament to our past as refugees.

Early this year, Christian and three colleagues decided to launch what they called #kunstjagdt—“art hunt.” Their plan was to spend six weeks using social media like WhatsApp and stories on the radio, on television, and in newspapers to search for the artistic equivalent of a needle in a very large hay stack.

Their reporting unfolded against the backdrop of the exploding refugee crisis in Europe and the Middle East. It was not hard to see parallels.

Then, as now, a desperate group of people sought to escape an increasingly terrifying situation. Then, as now, most countries in the world turned their backs. It’s sometimes suggested that German Jews of the 1930s were a delusional group, waiting far too long to flee a country in which they had grown too comfortable. The truth as documented by the Art Hunt team is that then, as now, there was hardly anywhere to go.

Jakob Engelberg applied to emigrate to the U.S. in 1934, shortly after Hitler came to power. He waited four years for his number to be called in America’s restrictive, Depression-era immigration system. My aunt told me years later that people who applied for U.S. visas just a few weeks later in 1934 died in the Holocaust.

My father and his sister recall that Hitler’s speeches and the Nazi Party’s program persuaded Jakob Engelberg that the Jews of Germany faced an existential threat, one sufficiently dire to persuade him to abandon a comfortable middle-class life as a traveling salesman living in one of Europe’s most beautiful cities.

The records dug up by the Art Hunt team suggest he was trying to live his life as an ordinary German. According to a Gestapo report Christian found in the Munich archives, Jakob Engelberg “read the rather liberal Frankfurter Zeitung but besides that was quite an apolitical person who didn’t show party flagging from his window on national holidays.”

I never got the chance to ask him precisely what persuaded him to try to leave Germany at such an early date. Jakob Engelberg died from a cerebral hemorrhage in 1941, long before I was born. (The German government would eventually make a small payment in compensation for his death, acknowledging that it was caused, at least in part, by blows to the head he received while at Dachau.)

The U.S. visas for Paula Engelberg and the two children, Melly and Edward, arrived in October 1938. Jakob’s visa was delayed because of his Polish nationality, a less-desirable category of immigrant under U.S. law for which fewer visas were issued. And so he was imprisoned in the barracks of Dachau on November 10, 1938, a Jew still waiting for his papers to leave the country.

These facts were confirmed by records recovered from archives in Germany and Switzerland by Christian and his Art Hunt colleagues: Fredy Gareis, Marcus Pfeil, and Carolyn Braun.

The search for the painting proved much more difficult. The team identified the man who stamped the precious visa: Wolfgang Gribi, a Swiss diplomat whose wife lived to be over 100. Unfortunately, she died two years ago.

They tracked down an expert on the art of Otto Stein who helped them identify 14 possible “suspects” that were similar to my family’s Mona Lisa. Most could be eliminated by date or provenance and my father eliminated several more in a Skype conversation (his first, at age 86). Eventually, the team narrowed it down to one particular painting that was bought by a private collector in Munich in 1950 after suffering what was described as “war damage.”

Christian flew to the U.S. and showed the painting to my father.

Not surprisingly, he could not be certain. It had, after all, been 77 years since he had seen the missing painting. Still, he said it touched him in ways that none of the other possibilities had.

There remained a piece of evidence that seemed to undermine the case for this particular painting. My father’s memory of what happened in November 1938, confirmed on many other key points, was that his mother had rolled up the painting before leaving for the Swiss consulate. Yet the newly discovered painting is on stiff paper that could not have been rolled.

As a journalist, of course, I’m familiar with the vagaries of human memory. To be fair, if my father’s recollection is accurate, the painting turned up by the Art Hunt cannot be The One. But it is also possible that the traumatic events of those days left my father with a memory that is inaccurate in this one regard. In all likelihood, we will never know.

My wife and youngest daughter flew with me to Munich recently to watch the premiere of a movie that tracks the four journalists on the Art Hunt. The story was as much about a new generation of Germans looking unblinkingly at the past as it is about a long-lost piece of art. The movie was shown at the Jewish Museum of Munich as part of an exhibition of both paintings.

In the question-and-answer session that followed the showing, there was a surprise: The Art Hunt team announced that the owner of the Stein painting had decided to give it to our family. Although he had bought it long after the war, and the identification is far from confirmed, Christian told me he didn’t feel right having it in his collection if there was any possibility it had been traded for a visa.

Jakob Engelberg’s Swiss visa was dated November 24, 1938—that year’s Thanksgiving. He was released from Dachau the next day and was out of Germany by early December. Weeks later, my father, then 10, began his life as a refugee, living with a distant relative in Lakewood, New Jersey. He was enrolled in public school and tried to learn in a language he spoke not at all.

As American presidential politics echo with calls for registries of Muslims and governors say they won’t accept Syrians whose circumstances are similar to my dad’s, I know what I’m thankful for. The two paintings are hanging at the Jewish Museum of Munich, side by side. In a few weeks, they will be returned to my father.

This story originally appeared on ProPublica as “The Painting That Saved My Family From the Holocaust” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.