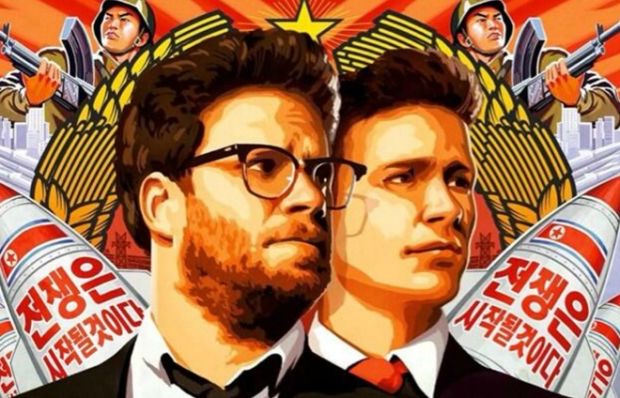

On the morning of November 21, 2014, hackers sent Sony executives—who were gearing up for the release of Seth Rogen’s North Korea-bashing film, The Interview—a grim holiday greeting: “We’ve obtained all your internal data including your secrets and top secrets. If you don’t obey us, we’ll release data shown below to the world.” The hackers made good on their promise, unloading into the public sphere a trove of emails, personnel information, and all sorts of other data. Most of the actual damage involved disclosed personnel records and damaged celebrity reputations. Among other things, producer Mark Rudin called Angelina Jolie “a minimally talented spoiled brat” for delaying his film projects, and producer Amy Pascal called Leonardo DiCaprio “absolutely despicable” after he passed on a Steve Jobs biopic.

A few politicians focused on the Sony cyber attack’s political and economic implications. “It’s a new form of warfare that we’re involved in,” Senator John McCain told CNN’s State of the Union, “and we need to react and we need to react vigorously.” Senator McCain’s condemnation was in large part a response to President Obama’s earlier acknowledgement that, while certainly an act of “cyber vandalism,” the Sony cyber attack doesn’t quite qualify as an act of war. Mike Rogers, the Republican chair of the House Intelligence Committee, was more reserved in his assessment. “You can’t necessarily say an act of war,” he said in an interview with Fox News. Rogers identified the underlying legal problem when he admitted, “We don’t have good, clear policy guidance on what that means when it comes to cyber attacks.”

So what was the cyber attack on Sony: vandalism, warfare, or something else? And if that attack didn’t cross the line into warfare, what would?

“The term ‘act of war’ is a dated one,” says Michael N. Schmitt, director of the Stock Center for the Study of International Law at the United States Naval War College, and one of the foremost experts on cyber attacks. “‘Act of war’ was a more common term when Congress would declare war. But the Geneva Conventions of 1949 dispensed with the requirement that war be declared before the rules of war apply.” Today, lawyers seldom use the term.

When people ask whether a cyber attack is an act of war, according to Schmitt, what people really want to know is (1) when is a cyber attack an unlawful “use of force” under the United Nations Charter? and (2) when can the victim state respond with physical force because the cyber attack qualifies as an “armed attack” under the Charter? While the difference is nuanced and important to most of the world, the U.S. does not distinguish between the two. Schmitt directed a group of 20 experts in creating the Tallinn Manual, which seeks to clarify and, to the degree possible, answer that question in the cyber context. The Manual includes eight factors that states can use to assess whether a cyber attack constitutes a “use of force.” Those factors, simplified, ask the following questions:

- Severity: How much damage did the attack cause?

- Immediacy: How quickly the consequences of the attack manifest themselves.

- Directness: How many intermediate steps had to occur between the attack and the consequences?

- Invasiveness: How much security did the attack have to bypass in order to cause its results?

- Measurability of effects: How easy is it to measure the damage caused?

- Military character: How involved was the military in carrying out the attack?

- State involvement: How involved was the state in carrying out the attack?

- Presumptive legality: Was the attack more akin to a military act, or was it merely propaganda, espionage, or economic pressure?

Schmitt and his group designed this agenda to help nations determine where a cyber attack falls on the spectrum of hostile acts. On one end of the spectrum are acts that don’t constitute acts of war, like espionage. On the other end are acts that do constitute a use of force—say, military aggression. It’s a relatively simple process to determine whether an act constitutes military force and, accordingly, if the victim nation has the right to respond.

“If you have a cyber operation that causes physical damage or injuries to a person, that’s an armed attack and you can respond forcefully,” Schmitt says. When a cyber attack doesn’t reach that threshold, things become more complicated. “Everyone agrees that certain cyber operations are clearly not armed attacks, for example, cyber espionage,” Schmitt says. “In between that [and uses of military force] … the law is not clear enough. Shutting down the national economy is probably an act of war, but short of that, we’re not certain.” Schmitt and other experts also agree that, despite Senator McCain’s contentions to the contrary, the Sony attack fell outside of the grey area and did not constitute an act of war.

So when would a cyber attack constitute an act of war? According to Schmitt and others, the only cyber attack that could have constituted an obvious armed attack was allegedly carried out by the U.S. and Israel.

In June 2010, Sergey Ulasen, a malware analyst working for a small Belarusian antivirus company, began investigating a customer request involving computer crashes and reboots. At first, the problem appeared to originate from application conflicts, or a misconfiguration in the operating system. But over time, Ulasen discovered that other computers on the customer’s network, even those with recently installed operating systems, were experiencing the same issues. Eventually, Ulasen and his team cornered the source: a sophisticated and powerful computer worm dubbed “Stuxnet.”

Unlike most viruses, which require users to move files from computer to computer, worms like Stuxnet spread on their own by exploiting software vulnerabilities. As the worm travels between computers, it can also carry a payload capable of disrupting computer systems. In this case, the Stuxnet payload had a very specific target: Iranian nuclear centrifuges.

By the time Stuxnet was finally discovered, it had already accomplished its purpose. The virus destroyed nearly one-sixth of the centrifuges Iran was using to enrich uranium, potentially for use in a nuclear weapon. Iranian officials remained tight-lipped, barely acknowledging the attack, let alone calling it an act of war. While Iran never openly identified the source of the attack, current and former U.S. officials, speaking anonymously, identified the U.S. and Israel as the authors of the attack.

Instead of calling out the U.S. or Israel or taking any overt action, Iran stayed quiet for two years. On August 15, 2012, a virus infected the computer systems of Saudi oil company Aramco and began deleting data from infected hard drives. While no physical damage resulted, it took Aramco several weeks to replace tens of thousands of hard drives to prevent further spread of the virus, causing significant disruption to the company. The next month, several large attacks took down the websites of financial institutions in the U.S. and prevented bank customers from withdrawing funds. Both the Aramco attack and the financial institution attacks were attributed to Iran. Even though two years separated the Stuxnet and Aramco/bank attacks, observers speculated that Iran was retaliating for the Stuxnet attacks.

Did either the Stuxnet virus or the Aramco and bank attacks constitute an act of war? “Stuxnet is probably the closest thing we’ve had [to an armed attack],” says Captain Todd C. Huntley, head of the National Security Law Department of the Office of the Navy Judge Advocate General. “You actually had physical destruction of the centrifuges. To achieve the same effect, you would have had to gone in and planted explosives or something similar to get that destructive behavior.”

Schmitt agrees: “Stuxnet would have qualified as an armed attack.” Per the Tallinn Manual definition, and as discussed above, a cyber attack can be an “armed attack” where the effects are “analogous to those that would result from an action otherwise qualifying as a kinetic armed attack.” If a missile or bullet or explosive could have caused the damage—physical damage or personal injury—a cyber attack with the same result is an armed attack. Stuxnet, likely developed by the U.S. and Israel, met that test.

Despite Stuxnet qualifying as an armed attack, Iran never went to the United Nations Security Council to claim that the attack violated the United Nations Charter’s prohibition on the use of force. Iran could have done so and sought assistance to respond to the attack. In fact, with the exception of Senator McCain’s recent comments and the Estonian defense minister’s response to a Russian-based cyber attack in 2007, there aren’t many instances where state officials have labeled a cyber attack an act of war. “I think the reasons are political and diplomatic,” Huntley says. “To compare it to something in the more traditional military sense, you have very few people calling the situation in Eastern Ukraine an international armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine. And in the cyber realm, one reason states are reticent to make that declaration is that it may come back to haunt them. If you call it an act of war, and later you carry out the same sort of attack, suddenly you’re saying your victim can send bombers back at you. States are treading lightly so they don’t set precedent they don’t want.”

Attribution—or a lack thereof—is another major obstacle that prevents nations from defining when a cyber attack can start a war. If a state can’t determine who carried out the attack, it’s difficult to know who to blame and whether the attack was even intended as an act of war. The Tallinn Manual addresses this to a degree with the Military Character and State Involvement factors, but a state can’t even apply the factors without knowing whether the military or state was involved. This challenge is on clear display with the Sony attack. At various times, investigators have attributed the attacks to North Korea, China, and even Sony employees. The FBI, after initially saying there was no connection between North Korea and the attack, has since concluded that indeed North Korea did carry out the attack—a conclusion that led to U.S. sanctions against the secluded country. (The U.S. is now certain that North Korea is behind the attacks, because the National Security Agency had already infiltrated North Korea’s computer network in 2010.)

“If we could somehow figure out the attribution piece, then a lot of issues go away,” Huntley says. “If you know who’s conducting the activity, then that gives you insight into intent. If it’s the Russian government, you know they have the ability to take things a step further. If it’s some hacker in his mom’s basement, you know there’s no intent or ability to raise the level of force that’s going to be used. Ultimately, the whole cyber problem is not a legal problem, it’s a technical problem.”

Determining whether a non-state entity is acting under the direction of the state further complicates the attribution problem. “If it turns out that the Sony attack can’t be tied directly to North Korea agents, but to a group of non-state affiliated individuals—North Korea’s line is that these were just patriots—what level of command-and-control or even sponsorship is required before a state is held responsible?” Huntley asks.

Huntley analogizes this problem to the Contras situation, when in 1986, after a complaint from the Nicaraguan government, the International Court of Justice found that the U.S. had sponsored the Contra rebels in their fight against the Nicaraguan government. More damning, the ICJ also found that the U.S. had encouraged the rebels to violate international law by providing them with a handbook, the Operaciones sicológicas en guerras de guerrillas. The manual, among other things, explained how to target and assassinate key civilians, including judges, police officers, and state officials. Despite the findings of U.S. influence on the rebels, one ICJ member dissented and the ruling was ultimately blocked by the U.S. in the United States Security Council. The difficulties of detecting a command-and-control relationship in the Contra situation illustrate how much more difficult detecting such a relationship will be in the cyber context.

That problem won’t soon be solved, according to Schmitt, from the Naval War College. Most of the cyber attack problems that remain will require patient waiting and watching: “We watch what states do over time and it sort of settles. State takes an action, no one objects, or everyone objects,” Schmitt adds. “We have a lot of people who want answers right now, but we’re in for a period of uncertainty.”

Lead photo by Jason Winter/Shutterstock.