That insomnia-inducing buzzing that you hear as a mosquito seems to dive-bomb you in the dead of night is the auditory pulse of a hunter. It’s not hunting using night vision, but by honing in on your smell and on your heat. And, if you have malaria, new research suggests that the insect can smell you especially well during some stages of the disease. At other stages of infection, by contrast, your mosquito-perceived stench appears to be bridled, which can protect you from further attacks.

That’s the funky conclusion of research involving mice at different stages of infection with the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. The research could help scientists develop new tools for diagnosing malaria in asymptomatic patients, for repelling mosquitoes, and for drawing mosquitoes into traps.

The findings may seem horrific, but they certainly aren’t unparalleled in the world of pathogens, which have been known to alter behavior and other traits of their hosts in ways that help them spread.

The findings suggest that the parasites affect their hosts’ odors to shield them from mosquito bites during acute stages of infection, keeping competing parasites out of the body as they take it over. Then the parasites appear to change the host smell—which is produced through the production of volatile compounds—to attract mosquitoes when they are most actively producing sex cells (the most infectious stage). The shift could draw disease vectors toward its host—helping the next generation of parasites clamber aboard fresh mosquitoes and take wing in a quest to find new hosts.

The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, involved research that used mice, which the Pennsylvania State University scientists say might mimic human disease responses. The paper builds upon prior malaria research that produced similar findings involving Kenyan children and canaries.

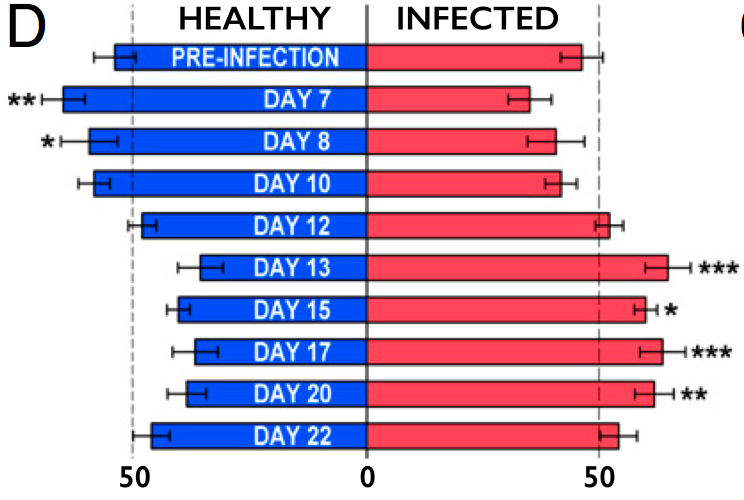

The scientists took samples from uninfected mice and mice at different stages of infection, placed them in two chambers of a small wind tunnel, then released mosquitoes to see whether they would exhibit a preference for the healthy or infected sample. Here are the results:

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (Chart: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences)

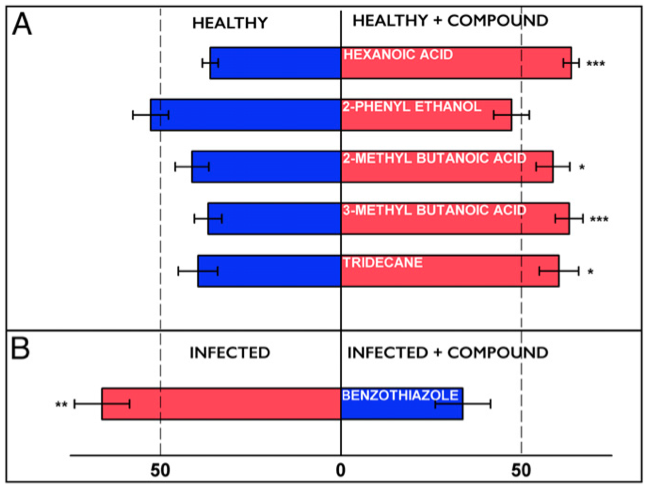

Next, the scientists compared the volatile compounds exuded by healthy and infected mice. They placed mice in the tunnel and added some compounds to see which ones helped attract or repel the mosquitoes:

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (Chart: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences)

The findings may seem horrific, but they certainly aren’t unparalleled in the world of pathogens, which have been known to alter behavior and other traits of their hosts in ways that help them spread. Rodents infected with Toxoplasma gondii, commonly found in kitty litter, for example, can become less fearful, increasing the probability that the rats will be caught and eaten by cats, helping the parasites (which also infect humans, with similar mind-altering results) find new hosts. Fungi can manipulate the behavior of infected ants, compelling their hosts to climb to locations ideal for spore dispersal. And thrips infected with a type of tomato-attacking virus chew more heavily on the plants, allowing the virus to spread.