There was a time when the contents of people’s bags were, more or less, private. A woman’s purse was a mystery; a businessman’s briefcase an anonymous mess of ink and paper.

Today, the practice of opening up one’s bag for display has become something of a national pastime. For years, celebrity magazines like Us Weekly and InStyle have made a show of asking stars what they carry in their handbags. The resulting annotated photo features, heavy on product endorsements and pricing information for cosmetics, are classic totems of faux intimacy between celebrities and readers. But more recently, the “what’s in your bag” feature has begun to migrate beyond gossip magazines.

These days The Wall Street Journal routinely itemizes the personal belongings found in the bags of successful executives—from international battery chargers to the peppermint Altoids that calm one fashion designer’s “paranoia about ‘bad breath.’” The Chronicle of Higher Education’s ProfHacker blog details what academics pack on trips, putting an emphasis on less-is-more, on-the-go productivity.

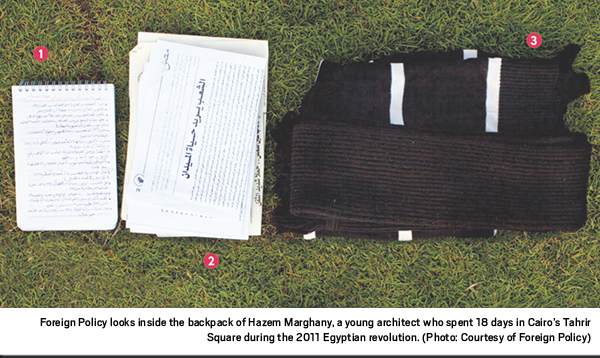

Foreign Policy’s “The Things They Carried” feature gives us a peek into the bag of a Tahrir Square protester (notebook, pamphlets, warm clothes); a Congolese rebel (computer with war-simulator games; Israeli pistol; Bible); and conventional wonks, like the Swedish foreign minister whose black Tumi carry-on, judging by its contents, could pass for that of a Silicon Valley programmer—save for his diplomatic passport.

This very public game of show-and-tell has come to include ordinary people too. Self-submitted YouTube videos lay bare the contents of purses and carry-ons. Entire Flickr groups are dedicated to displaying what members keep in their clutches, backpacks, and messenger bags. These user-generated forums are anything but a free-for-all. Stern, almost clinical guidelines sketch out the ideal “what’s in your bag” photo. For consistency, one Flickr group with more than 27,000 members bans photos of shopping bags, makeup bags, photographer’s kits, and “any pet or a person sitting in a bag.”

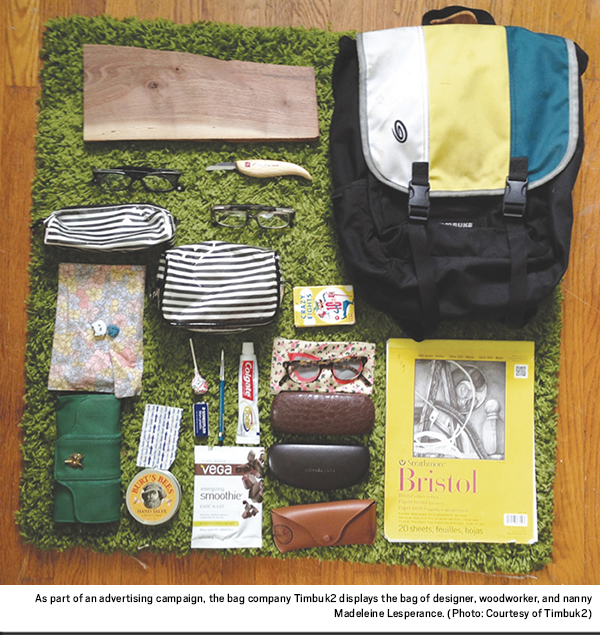

Perhaps the purest expression of the phenomenon is found in The Verge, a tech-focused online magazine founded in 2011, which unveils the bags of media and tech workers. Color images, usually taken from above, show items arranged around the bag in an orderly fashion. The photographs almost always show a laptop and/or tablet with its accompanying cables; then there might be a book, a pair of sunglasses, a couple of pens, and maybe a protein bar or some chewing gum. As with InStyle, annotations in The Verge tend toward enthused product endorsements, with Revlon and Maybelline replaced by Apple and Moleskine. The bags’ owners often emphasize their efforts to keep their cargo sparse, bashfully admitting to having removed stray snacks and receipts prior to the photo shoot.

What’s striking is the lack of variation in these shots. Another bottle of hand sanitizer, another MacBook Air—there’s rarely anything new to see. The images are clearly staged; the voyeuristic pleasures pretty minimal. Yet the content of the bags is still “anthropologically meaningful,” says Dominique Boullier, a French sociologist who has studied these photos with a team of researchers at Sciences Po. While the images might not tell us too much about an individual (save whether she favors Macs or PCs), “they do re!ect the environment he or she inhabits.”

If Kim Kardashian’s on-the-go kit embodies a certain standard of round-the-clock female beauty, these new bags we see convey different, but equally pervasive, norms: productivity, transparency, a blurring divide between work and life, and a willingness to engage in unplanned, spontaneous labor.

Predictably, marketers have jumped on the bag-wagon: the bag maker Timbuk2 has filled its website WhatsInYourBag.com with customer-submitted pictures to show how well its products can accommodate its clientele’s busy, mobile lifestyles.

Bag-sharing has also emerged against the backdrop of large-scale online data collection and public surveillance, Boullier notes: “The bag traditionally is designed to hide your personal activities—but now you display it because you know that no matter what you do, everyone will know who you are, what you’re doing, where you live.” When you’re used to arranging your tiny shampoo bottles in a clear Ziploc, having your bag searched on your morning commute, or putting your vacation photos up on Facebook, it’s no big deal to spread these objects out for the world to see—especially if you can pick and choose what to include.

Real bags are messier and more revelatory than what typically shows up online. The Hairpin, an impish blog run by young women, has reacted to the “what’s in your bag” boom by running a “What’s Actually in Your Handbag Right Now” column. The pictures show a mess of pens, tampons, candy, and assorted junk; they lack the pretense of the aspirational, clutter-free collections that so many people try to reproduce.

Ellie Brown, a fine-art photographer, spent almost two years shooting the strikingly diverse contents of bags carried by ranchers, schoolchildren, grandmothers, and other people not likely to appear in The Verge or Us Weekly. Weary of people’s impulse to self-censor, Brown gave her subjects clear instructions not to remove anything from their bags. “When I took the photos, especially with women, there was a lot of self-shaming, saying, ‘I’m such a mess, I’m sorry,’” Brown says. “People feel like they have to present their best selves in the pictures.”

The Hairpin’s column mocks the artifice of staged images and the pseudo-Zen idea that fitting all your necessary, well-chosen items into a small space amounts to a kind of minimalist enlightenment. And Brown’s “real” bags reveal a certain hierarchy in who gets to travel light (young city dwellers whose essentials take up little space) and who must bear the burden of their tools, like livestock inspectors and energy linesmen.

The “what’s in your bag” phenomenon helps us situate ourselves—and others—within this hierarchy. “It helps us understand our place in society,” Boullier says. When the lines between what’s public and what’s private and between work and play are more blurred than ever, the safest move is to observe, to compare—and to conform.

This post originally appeared in the January/February 2014 issueofPacific Standard as “Baggage Claims.” For more, consider subscribing to our bimonthly print magazine.