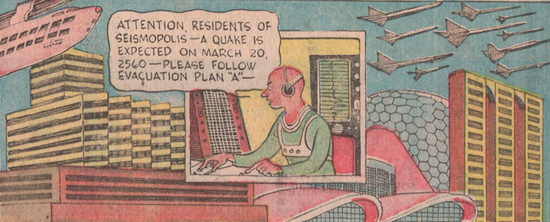

Portion of the September 20, 1960 edition of Athelstan Spilhaus’s Sunday comic strip, “Our New Age”

On March 27, 1964, a 9.2 megathrust earthquake rocked Alaska. It was the most powerful earthquake to ever hit the United States and 143 people lost their lives. The earthquake lasted almost four dreadful minutes as office buildings in Anchorage folded in on themselves and homes tumbled down cliffs.

No one saw it coming. Just as no one could predict Monday’s 6.2 earthquake in Guatemala (which thankfully didn’t cause any serious damage).

There’s no surefire way to predict when an earthquake will strike (and some experts feel that as a practical matter the push for prediction should be replaced by a mania for mitigation). But we do have the ability, using present-day technology, to develop an early warning system like those already being used in Japan and Mexico.

As Ed Yong explains over at BBC Future, there’s a tremendous difference between long-range earthquake prediction and using the tools of an early warning system to warn people just moments before things get dangerous:

At one extreme, we can calculate the odds that big earthquakes will strike broad geographic areas over years or decades—that’s called forecasting. At the other extreme, early warning systems can relay news of the first tremors to people some distance away, giving them seconds to brace themselves. But the ultimate goal—accurately specifying the time, location and magnitude of a future earthquake—is extremely difficult.

The Los Angeles Times recently reported on a call by the U.S. Geological Survey, the California Institute of Technology, and UC Berkeley to begin developing an early warning system for earthquakes. However, no one knows where the estimated $80 million needed for such a program would come from.

An early warning system in California would be the first such program in the U.S. and has the potential to help save lives. But it still pales in comparison to the dreams of 20th-century futurists.

The image above is from the March 20, 1960, edition of the Sunday comic strip “Our New Age,” which ran in newspapers around the world from 1958 until the mid-1970s. The strip was written by Dr. Athelstan Spilhaus and shows a bald, jumpsuit-wearing man at a control panel broadcasting a message to the people of “Seismopolis.” Follow evacuation “Plan A,” he tells the residents of this unfortunately named city. (Seriously, why would you live in a place called Seismopolis?) But even futurists of the 20th century understood that perhaps long-range prediction was still a ways out—this vision from Spilhaus was set in the year 2560.

Last year I felt my first earthquake. It wasn’t big—just a 3.4 jolt—but it was centered close enough to where I live in Los Angeles that I jumped out of bed, unsure of what was happening. Having grown up in the Midwest, I’m much more accustomed to braving six-foot snow drifts, 40-below wind chills, and dodging tornadoes than having the very earth tremble whenever it damn well pleases.

Another earthquake rattled me just a few days after the first, again doing no damage but rousting me from bed once more. They weren’t very consequential quakes, but they were both centered so very close to my apartment that I had to question (while staring at the ceiling, wide awake) why the hell I was living in such a clearly condemned place like L.A.

Wait, does Los Angeles get renamed Seismopolis by the year 2560?