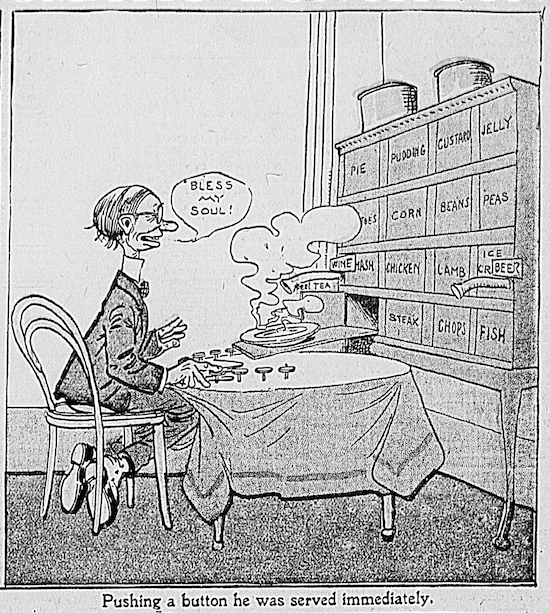

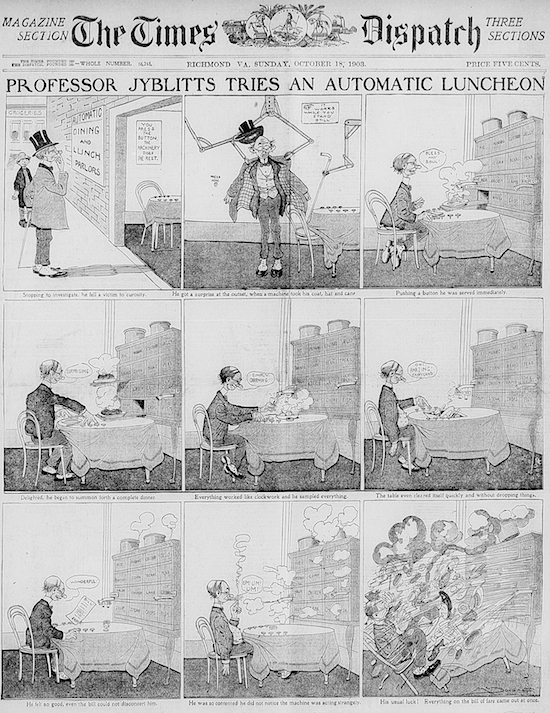

Partial cartoon about push-buttons (October 18, 1903 Times Dispatch in Richmond, Virginia)

Authors, advertisers and inventors of the 1950s and ’60s all promised us that the push-button was the key to a future of leisure. In the world of tomorrow you’ll just push a button to clean the house. Push a button and dinner will be served. You’ll even push a button to walk the dog.

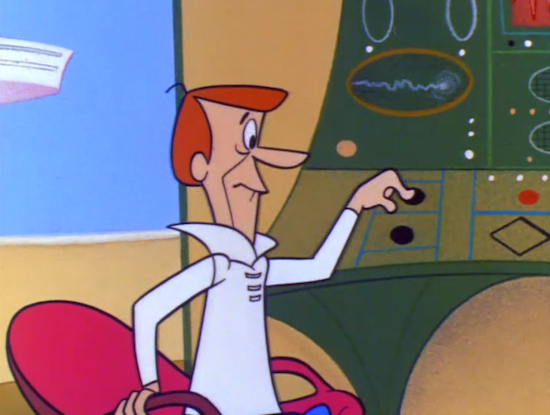

Nowhere was this promise made more explicit than in the 1962 animated ABC series The Jetsons where George pushes a button just a few times a day to earn his living. Meanwhile, his wife Jane complains of “push-button finger,” a malady that strikes the homemaker of the future who pushes maybe half a dozen buttons in the course of a day.

But the promise of the push-button as the gateway to a life of leisure has its origins far earlier than the Space Age. Dating back to the late 19th and early 20th century, the push-button quickly evolved into the perfectly simple symbol of modernity back when electricity itself was first being introduced to American homes.

George Jetson’s push-button world of leisure (from the first episode of The Jetsons in 1962)

Whether it was for ringing doorbells, illuminating lamps, hailing domestic servants, or turning on any number of new electrical appliances, the push button arrived in full force as an interface that was supposed to save time and generally make life easier. Just push a button, and it’s all done automatically!

As Americans came into contact with more and more machines in the late 19th century, the push button was supposed to ameliorate heightened anxieties about the complexity of life—what Rachel Plotnick describes as a “pervasive cultural craving for efficient relationships between humans and machines.” Plotnick writes about the button as the interface of leisure in her 2012 paper “At the Interface: The Case of the Electric Push Button, 1880-1923.”

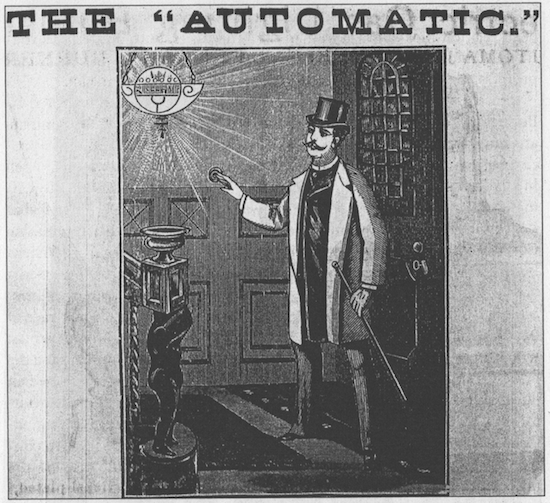

The wealthy were the early targets of this message praising the “automatic” power of the push-button, as they naturally were the early adopters who could afford things like electric light and push-button appliances. But the button was sold as a symbol of luxury—the interface of the future—even before household electricity was the norm. Plotnick uses an ad from 1888 as one example of when the wealthy embraced the push-button even in the seemingly old fashioned use of gas lighting:

One tactic employed by manufacturers and distributors of push buttons and their associated devices involved promoting these switches as pleasurable luxuries that would make life easier for the wealthier set. J. H. Bunnell & Co., in its “Illustrated Catalogue and Price List of Telegraphic, Electrical & Telephone Supplies, No. 9” of 1888, for example, advertised “The Automatic,” a wall-plate control system that would allow its opulently dressed user to turn gas lights on and off remotely. Outlining the button’s various uses, the catalog described a house entirely run by buttons: “One in the front hall, to be lighted by buttons placed at the front door and also by the chamber door, or one in the cellar, with press-bttns [sic] or keys at the head of the cellar stairs… or one in the family chamber, to be lighted from the bedside chamber door, are all luxuries which, after accustomed use, become necessities to household comfort.”

1888 ad for a push-button switch which targeted the wealthy (Smithsonian/Plotnick)

As the 19th century gave way to the 20th the push-button would become more associated with the the electrical rather than gas-driven promises of the future. And the push-button was able to conjure electrical luxuries—as if by magic. Plotnick explains:

In order to sell this vision of electricity, experts often relied on tropes of magic and effortlessness to embody users’ experiences with buttons. In 1916, for example, the Society for Electrical Development chose a poster for “America’s Electrical Week” from among 781 entries that whimsically celebrated the benefits of button-powered electricity. An electrician, in a positive endorsement of the poster, enthused: “Gone is the ancient lamp. Now it is the gentle touch of a button and forthwith comes the Genie, Electricity.” The campaign and its admirers indicated that users needed no knowledge or skill to make electrical miracles possible, as long as a button stood at hand. The user interface heralded electricity seemingly from the heavens, making electrical circuits, wires, plugs, and other mechanisms invisible.

Of course, just like The Jetsons, Americans of the early 20th century weren’t above poking fun at the idea that push-buttons would solve all our problems. The October 18, 1903 issue of The Times Dispatch in Richmond Virginia ran a cartoon featuring Professor Jyblitts who sits down for an “automatic luncheon.” A sign on the wall reads “You press the button, the machinery does the rest.” Robot arms help him with the removal of his hat and coat and he simply presses buttons to order and be served lunch. Pressing a button even automatically clears the table. However, by the last panel his push button lunch is ruined by the smoking, hulking machine that just moments earlier seemed like a godsend.

Today we push buttons in elevators, on our coffee makers and in our cars without thinking twice about the often complex machinery that makes these magical devices work. But it would seem the phrase “push-button” itself has picked up a fair number of negative connotations on its journey here to the early 21st century.

While an electric car’s “push-button start” may be a positive selling point, we’re more likely to hear it used as a derisive term to bemoan the distance humans have from the cold, mechanized consequences of those buttons. With each passing year we seem to move closer to fully automatic destruction with what critics call push-button war, but as a Korean War-era cartoon from 1952 lamented, we have yet to invent something like push-button peace.