Frederick W. Schmidt’s invention of an animated retail window diorama (1922)

While walking through the Westfield mall in Culver City, Calif. last week my eyes were inundated with a seemingly endless landscape of screens all begging for my attention. The mall pulsed with a sort of pseudo Blade Runner glow. Rectangular human-scale screens at eye level bounced light at passersby while a probably 20-foot-tall video screen loomed over the Christmas tree at the center of the mall—simply wanting to be noticed, hoping to steal just a moment of your time.

But long before the invention of the television screen (and the indoor mall, for that matter), the window display was king. Display windows were the dominant method for stores to advertise their wares before the invention of broadcast TV, which “brought the virtual ‘window’ right into the consumer’s home,” as historian Gayle Strege explains in a 2009 paper.

Retailers spent big on those window displays. According to Strege, window display pioneer Arthur Fraser oversaw a staff of 50 carpenters and artisans at Marshall Field’s in Chicago from the 1890s into the 1940s. Fraser had turned the simple thoughtless window display, with goods piled onto each other haphazardly, into a commercial art inspired by the theater. In the boom of the 1920s, when the U.S. economy was soaring and personal credit became all the rage, Fraser was working with budgets as high as $175,000 per year (about $2 million adjusted for inflation) to draw in customers to part with their dollars.

Though Fraser is the window display pioneer that history remembers best, there were dozens of other people in the early 20th century who worked on turning the storefront window into more than a simple stack of goods. In 1922 Frederick W. Schmidt of Philadelphia developed an animated store window that was meant to draw the eye from people passing on the street.

The November 1922 issue of Science and Invention magazine featured a short article about his recently patented invention, which included clocks, an airplane, a flag flapping in the wind and other animated features. From the magazine:

The possibilities and variations of Mr. Schmidt’s idea are practically limitless. Briefly considered, the apparatus comprises a painted scene with certain parts made movable, such as the blades on a windmill, a small boat, an airplane, etc.; the picture is projected through the lens upon a screen in the show window by the reflection principle, similar to that used in the well-known postcard projectors. In other words, the light from powerful incandescent lamps is thrown upon the scene, and the reflected light is projected through the lens to the screen.

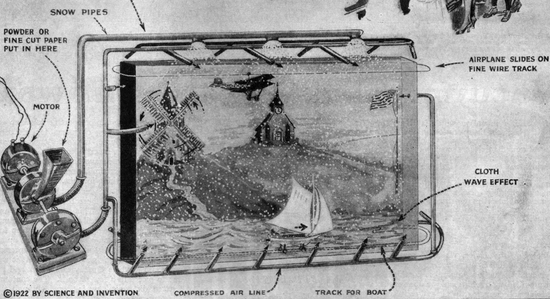

The moving parts of the scene, such as windmill blades, walking or dancing figures, etc., may be operated in a number of different ways, such as by clockwork or by electric motors. One interesting scene provided for in Mr. Schmidt’s patent, is a snow scene. To produce the effect of falling snow, powder, such as flour, or else very finely cut white paper, is fed into the hopper on top of one of the small motor-driven air blowers, and this flour or cut paper is carried up to the openings in the air delivery pipe at the top of the scene, from whence it is blown out and downward, in a very realistic manner.

An illustrated explanation of how Schmidt’s animated diorama display worked (1922)

These animated store window displays are still in use today by retailers, especially around the holidays. Though I have yet to see my dream window diorama: a very special Blade Runner Christmas.