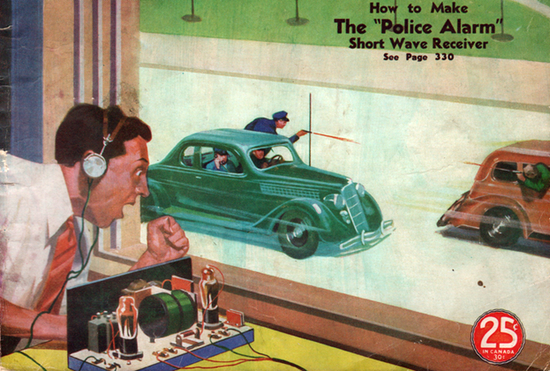

Portion of the cover of the October 1935 issue of Short Wave Craft magazine

Yesterday I had the rather strange experience of reading a tweet about a grass fire burning not far from my apartment. Not five seconds later I heard fire truck sirens in the distance. This, it would seem, is the new pace of breaking news.

I follow about half a dozen Los Angeles police scanner accounts on Twitter, each with their own beat: Venice, Beverly Hills, Culver City, Koreatown, and LAScanner. These accounts are run by people who tune into radio frequencies used by police, fire, and medical responders in order to tweet about events as they happen.

Social media sites like Twitter and Facebook have radically sped up the pace at which news spreads. This immediacy is even more apparent in these police scanner accounts all across the U.S. Even the raw audio feeds are online, with breaking news of crimes and medical emergencies all around the country little more than an Internet connection away.

Back in more analog days, tuning in wasn’t quite so easy. In fact, private citizens would have to build their own police radio receiver if they wanted to hear the action.

The October 1935 issue of Short Wave Craft magazine explained how anyone could build his own “police alarm” shortwave radio receiver. The cover featured a rather excited looking man wearing headphones as he looked out of his window at the police chase below.

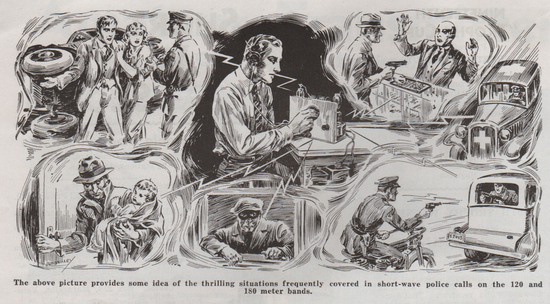

The appeal of police scanners is and always has been a kind of law-and-order voyeurism. Robberies, car crashes, burglaries, high-speed chases, and even kidnappings were touted by Short Wave Craft as the kinds of sordid events you’d be privy to with a “police alarm” radio receiver. They even included an illustration showing the kinds of “thrilling situations frequently covered in short-wave police calls on the 120 and 180 meter bands.”

The “thrilling situations” you might hear about on your DIY police radio receiver (1935)

Inside the magazine, the article by Walter C. Doerle touts building a receiver as not merely a voyeur’s plaything, but a very serious learning tool for those men who have dreamed of becoming a policeman ever since they were a “little shaver of a kid.” He argues that simply by listening in you can serve the public good:

Why not take advantage of the many free “courses” offered to you through the use of a short-wave set as herein described and become a public officer in the Police Corp? But you say, what are these courses? Well, in stenographic language, our recent kidnap cases are enough to baffle the brains of many brilliant police forces—this is the “college course” and it tops the list of courses as requiring the best minds for permanent solution. As a second course, murdering ranks next, petty burglaries are third, and auto accidents are at the bottom. So you see unless full advantage is taken of radio in the short-wave field, it is hard to be convinced that scientists have made a worth-while contribution to our civilization.

The article included detailed schematics for precisely how to build your own inexpensive “amateur sleuth” radio receiver, which used a 2-tube regenerative circuit made popular by Doerle in the early 1930s. Today, citizen voyeurs such as myself have no need to get our hands dirty with circuits or wires or antennas, as the Internet continues its often strange and sometimes beautiful march forward. But Doerle would no doubt be proud of all the amateurs doing our part simply by listening in his “battle against crime.”

If you want to read more about the world of police scanners in the age of social media, I highly recommend this interview with the man who runs @LAScanner on Twitter.