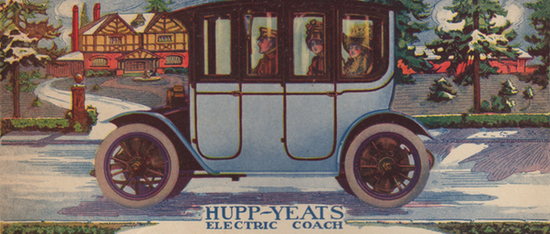

Magazine advertisement for the Hupp-Yeats electric car (January 27, 1912 Literary Digest)

In 1910, Thomas Edison declared, “In 15 years, more electricity will be sold for electric vehicles than for light.”

Edison’s prediction would prove woefully inaccurate, but it’s easy to understand his enthusiasm. The first decade of the 20th century was a golden age for electric vehicles. According to the IEEE, a full 28 percent of the 4,192 cars produced in the United States in 1900 were electric. Of course, Edison in 1910 also had a vested interest in seeing electric cars succeed, as he’d been working on more efficient batteries to put in them for nearly a decade. But there really did seem to be momentum building for the electric car.

By 1910, cities like Philadelphia, Cleveland, New York and Baltimore all had electric charging stations. And although internal combustion engine vehicles outsold electric vehicles during the previous decade, gasoline’s future dominance was not yet seen as a certainty in 1910.

Electric car companies like Baker Electrics in Cleveland (Thomas Edison was a customer), Hupp-Yeats in Detroit, Rauch & Lang in Cleveland, Columbus Electric in Columbus, and Anderson Electric in Detroit all took out numerous ads in the weekly magazine The Literary Digest. These electric car ads appeared alongside their gas-powered competitors and did their best to differentiate themselves—often as the more debonair choice in transportation. The Literary Digest had broad national appeal, but boasted that its readership included a large proportion of wealthy businessmen who would be able to afford the luxury of a clean and efficient electric vehicle.

Electric car advertising of this era touted the many benefits of electrics, such as its ease of use compared to gas-powered cars. Until the development in the early 1910s of the electric starter for gas-powered cars, electric cars were easier to start than internal-combustion cars because they didn’t need to be hand cranked. The electric car was also seen as cleaner since they didn’t pump out noxious exhaust along the road. This perception of cleanliness led them to be seen as more “refined,” catering to a wealthier clientele. Of course, this appeal to wealthier customers was also driven by the electric car’s higher operating and manufacturing costs.

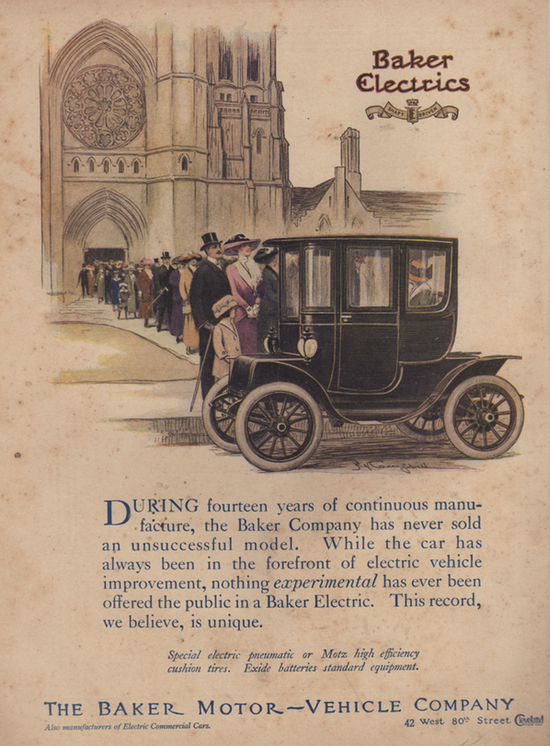

Magazine ad for Baker Electrics (March 16, 1912 Literary Digest)

As a whole, the young auto industry dealt with consumers who were wary of new “experimental” technologies. But the electric car industry was hit particularly hard with skepticism around 1910 thanks to a mix of high expectations and rapid technological advancement by the gasoline-powered car manufacturers since 1900. As David A. Kirsch explains in his book, The Electric Vehicle and the Burden of History:

In absolute terms the electric vehicle of 1910 was vastly superior to the first-generation vehicles produced at the turn of the century; but relative to both expectations and the internal combustion vehicle of 1910, the passenger electric car was actually further from commercial viability than was its predecessor.

And thus, the electric car makers like Baker sought to combat the image that they were still working out the kinks, like in the ad above from the March 16, 1912 issue of Literary Digest.

During fourteen years of continuous manufacture, the Baker Company has never sold an unsuccessful model. While the car has always been in the forefront of electric vehicle improvement, nothing experimental has ever been offered the public in a Baker Electric. This record, we believe, is unique.

Advertisement for a Baker electric vehicle (January 8, 1910 Literary Digest)

The Baker Electric ad above appeared in the January 8, 1910, issue of The Literary Digest and sells the Baker as aristocratic with the tagline, “The Aristocrats of Motordom.”

Every Baker Electric, from the dignified four-passenger Coupe to the racy Runabout, represents the highest attained degree of silence, safety, elegance and dependability.

The Baker Electric, with its superior speed and mileage capacity, instant readiness for use and economy of maintenance, is the ideal car for city and suburban use.

Full ad for the Hupp-Yeats electric car (January 27, 1912 Literary Digest)

Interestingly, the Hupp-Yeats ad was playing on ideas of nostalgia, promising the luxury enjoyed by the wealthy of yesteryear combined with all the cutting-edge technology the 20th century had to offer. Such luxuries, of course, came at a price. The Hupp-Yeats Imperial of 1912, advertised for $5,000 above, would cost roughly $110,000 today when adjusted for inflation.

‘A revival of the golden age in coach building.’ So writes a well-known critic in speaking of the Hupp-Yeats. And in truth no monarch in state procession, no courtly retinue, ever rode in greater luxury, greater elegance and greater ease than are exhibited in these late Hupp-Yeats models.

But the Hupp-Yeats design, low-hung, safe and exceptionally graceful, represents the first adaptation of coach construction to modern needs. In medieval times coach bodies were swung high, because even in the large cities the streets were mere seas of mud often over the hubs. Modern coach-builders followed this design blindly. And on the smooth streets of a modern city it looked awkward and stilted, was dangerously liable to skid, and was difficult to ingress or egress.

The Hupp-Yeats, with its low-hung body, is the ideal twentieth-century town car. The low center of gravity makes skidding, swerving or overturning a practical impossibility, and it is as easy to enter or leave as to step from one room to another. Women with memories of torn skirt hems and sprained ankles will appreciate this feature.

Ad for a Rauch & Lang electric car (January 8, 1910 Literary Digest)

Again we see the electric car being advertised as a vehicle of refinement, as in this ad above for Cleveland-based Rauch & Lang. The ad in the January 8, 1910, issue of The Literary Digest also claimed the car was so safe and rugged enough that (even) a woman could operate it.

Any woman can run the car safely.

All the power and a strong brake are controlled through one simple lever.

The car can’t possibly start ’til this lever is first in the neutral position. Yet all power can be shut of instantly with the lever in any position. The car is accident-proof.

Ad touting the electric car as a more enjoyable alternative to street cars (March 9, 1912 Literary Digest)

It wasn’t just the gas-powered cars that electric cars positioned themselves against. They also wanted to be seen as a much more enjoyable alternative to public transportation, as in this ad for Columbus Electric from the March 9, 1912, issue of The Literary Digest.

The well-dressed woman who must go home from the theatre on the street cars, scarcely sees or enjoys the last act of the play. She sees instead only the disagreeable ordeal that is to come. To her the privacy of a car like the Columbus Electric would mean more than you could ever guess—until you ask her about it. Our Model 1225, shown above, is typical of the various models we make. It will pay you to investigate.

At the electric car’s peak in 1912 there were roughly 30,000 zipping around on American roadways. But this was a drop in the bucket compared to the overall car market, which was exploding thanks to the introduction of Ford’s gas-powered Model-T in 1908. In 1912 alone, Ford sold more than 200,000 Model-Ts. By the end of World War I, electric vehicles had more or less lost their long battle with the internal combustion engine.

There are a number of reasons that the electric car fizzled in the United States while the internal combustion engine shined—new oil discoveries made the price of gas very competitive with electrics in the 1900s and 1910s. Also, as higher quality roads were built, people could drive greater distances and so sought cars with a greater range for “touring,” an advantage of the internal combustion engine over the electric motor. And frustratingly for electric car owners, a lack of standards within the electric car industry as a whole meant that finding a place to plug in that fit your particular vehicle could be difficult.

While today’s car consumer has a wide selection of all-electric vehicles, compared with even a decade ago, they still face many of the same hurdles of those drivers making expensive decisions a century ago. Baker Electrics touted an all-electric vehicle in the year 1911 that had supposedly achieved over 200 miles in a single charge. But this was far from the norm (and not independently verified). This same concern over the range of an electric car is often the most pressing question from perspective electric car buyers today.

With increased range, greater dependability and concern for the effects our gas-guzzling cars are having on global climate change, the electric car may have another golden age up its sleeve.