About 65 percent of the United States’ total jail population are pre-trial detainees who haven’t yet been convicted of a crime. While a small percentage of those 460,000 inmates—all of them in county and city jails—are held because a judge concludes they’re either a flight or safety risk, the majority are there simply because they lack the financial resources to pay bail.

In recent years, the bail system has been criticized by leaders and advocates across the political spectrum. In a new report from the Hamilton Project at the Brookings Institution, researchers Patrick Liu, Ryan Nunn, and Jay Shambaugh provide one more piece of evidence in support for systemic reform: It’s costing the United States a lot of money—over $15 billion per year, in fact.

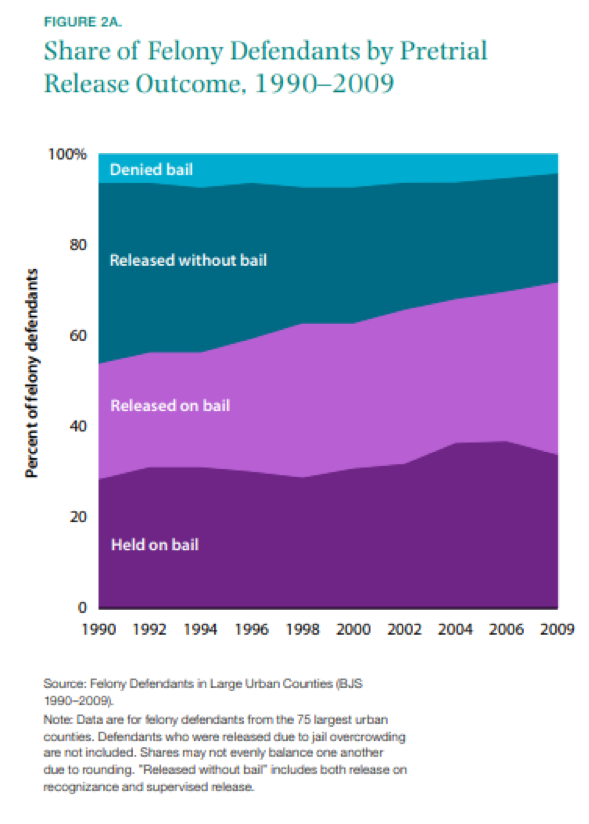

Between 1990 and 2016, the percentage of inmates in jails who hadn’t yet been convicted of a crime increased from approximately 50 percent to 65 percent. This trend was accompanied by a significant jump in the proportion of defendants required to post bail in order to be granted a pre-trial release. The chart below, from the Hamilton Project report, illustrates this trend:

All in, the proportion of defendants required to post bail in order to be released increased by 19 percentage points—from 53 percent to 72 percent—while the percentage of defendants released without posting bail declined by 15 percentage points. The trends are similar for both violent and non-violent offenses, according to the researchers:

[I]t appears that defendants who were previously considered sufficiently low risk to be released without bail are now being assigned bail instead, and this has contributed to the rise in the share of the incarcerated who are not convicted. Furthermore, the share of felony defendants viewed as significant risks—and who therefore are not eligible for release—has remained below 10 percent since 1990. The fact that 40 percent of felony defendants are not released pretrial is not primarily a safety issue, but a financial one.

There are substantial costs associated with detaining all these people awaiting trial (many of them for months at a time). On average, it costs approximately $28,000 per year to house an inmate, and pre-trial detainees also aren’t able to work and contribute to economic output. According to the Hamilton Project researchers, it costs about $11.7 billion per year to house all these pre-trial detainees; when the foregone economic output of detainees is factored in, the total direct costs of the country’s pre-trial detention system reach almost $15.3 billion per year. (The researchers weren’t able to tally the “benefits” of pre-trial detention, which include less spending on tracking down defendants who “skip bail,” and possibly fewer crimes committed by detainees out on bail.)

Of course, the costs of the bail system, which fall disproportionately on low-income Americans who lack financial resources, extend far beyond the direct costs of incarceration.

In several recent studies, researchers have utilized the quasi-random assignment of judges—and variations in judges’ proclivities to release defendants with or without bail—to assess the causal effects of pre-trial detention. They’ve found that pre-trial detention significantly increases the likelihood that a defendant is convicted; the effect is due largely to an increased likelihood of defendants pleading guilty. In one such paper, a team of researchers concluded that “the assignment of money bail leads to a 12 percent increase in the likelihood of conviction and a 6-9 percent increase in recidivism.” (Several other papers have also found that pre-trial detention increases recidivism, likely in part due to economic reasons.)

While a guilty plea can reduce jail time—and there’s some evidence that defendants are more likely to plead guilty when they’re afraid of losing their job or when they have children—it can also do serious long-term economic damage. In one 2010 study, researchers at Pew Charitable Trust found that incarceration “reduces hourly wages for men by approximately 11 percent, annual employment by 9 weeks and annual earnings by 40 percent.”

In another paper utilizing quasi-random judge assignment, published earlier this year in the American Economic Review, researchers Will Dobbie, Jacob Goldin, and Crystal S. Yang found that pre-trial detention increases the likelihood of conviction, due largely to an increased incidence of guilty pleas. They also find that, three to four years after the bail hearing, pre-trial release increases the probability that a defendant is employed in the formal labor market by 9.4 percentage points and increases the probability of having any income by 10.7 percentage points.

Dobbie, Goldin, and Yang also conduct a more comprehensive cost-benefit analysis of the costs of pre-trial detention. They conclude that “the net benefit of pretrial release at the margin is between $55,143 and $99,124 per defendant. The large net benefit of pretrial release is driven by both the significant collateral consequences of having a criminal conviction on labor market outcomes and the relatively low costs of apprehending defendants who fail to appear in court.”

As the Senate’s recent passage of a bipartisan criminal justice reform bill indicates, there’s an impetus across the political spectrum for a meaningful change to the carceral system. Perhaps the bail system will be the next target for amelioration.