The international commodities trader Cargill Inc. has unveiled a prototype: a kite-powered cargo ship that could reduce by as much as a third the amount of fossil fuel it takes to operate the enormous vessels that move the world’s goods.

Alcoa Inc., one of the world’s biggest aluminum makers, gives away a cellphone app that tallies the cash to be made from recycling beer and soft drink cans.

The chemical giant E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Co. says it not only has made impressive strides in improving its environmental performance, it is also building a lucrative new revenue stream from helping other companies reduce their carbon footprints.

A sea change washed over the corporate world gradually during the last two decades — and then rapidly in the last few years — as concerns about global warming, environmental degradation and resource scarcity intensified. Companies across the economy have embraced sustainability, launching social and environmental welfare projects, greening their supply chains, cutting energy use, developing environment-friendly products and — perhaps most noticeably — churning out sustainability reports that chronicle their good works.

While some critics complain that corporate sustainability and responsibility programs waste resources and hurt shareholder value, the battle of the boardroom has been won at most big companies. About 80 percent of the Fortune 500 issue sustainability reports, according to a 2008 survey. A report published last December found that 73 percent of 378 large and medium-sized companies around the globe had a sustainability program in place or were developing one.

Huge efforts in corporate self-improvement — for example, the $10 million deal Dow Chemical Co. inked in January to have The Nature Conservancy evaluate Dow’s impact on the environment —have become almost commonplace. Within the past year, General Motors has moved half of its plants to “zero waste” operations, meaning they don’t send anything to the landfill. Procter & Gamble has pledged to start making the packaging for its 23 brands of consumer goods from renewable or recycled materials. Even Koch Industries, known as a corporate leader of climate change denial, counts its carbon emissions these days.

Just the same, many corporations appear to be living double lives in regard to sustainability and social responsibility. “A lot of what we see corporations doing is really greenwashing, or in the case of water, bluewashing,” says Wenonah Hauter, the executive director of Food & Water Watch, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit watchdog group. “You can just look at what’s taking place in Congress right now with the attacks on EPA regulations and health and safety rules. It’s these multinationals who are doing the heavy lobbying and influence peddling.”

The list of corporate misdeeds that belie sustainability rhetoric is long. In the last two years alone, Corporate Responsibility Magazine, which publishes one of the more widely accepted corporate citizenship rankings, “The 100 Best Corporate Citizens,” has issued eight yellow and three red “penalty cards” to companies in the competition. A yellow card is meant to signal “caution” but doesn’t impact the ranking. A red card, on the other hand, disqualifies a company from the list for three years.

3M, for example, received a yellow card and ExxonMobil was red carded this year for contaminating groundwater. Occidental Petroleum Corp. received a yellow card over a human rights and environmental contamination lawsuit regarding the alleged pollution of indigenous land and the Amazon River in Peru.

All the “carded” companies have issued reports, press releases and other pronouncements detailing their corporate good deeds. In fact, companies rarely mention controversies in their corporate citizenship missives. (But some do: Johnson & Johnson lists its recall of Motrin as one of “Our 2009 Successes,” while also expressing regret over the episode.)

Such moves highlight one of the biggest complaints from critics of the corporate sustainability movement: Companies often use the reports to pat themselves on the back for merely complying with the law or taking advantage of government incentives.

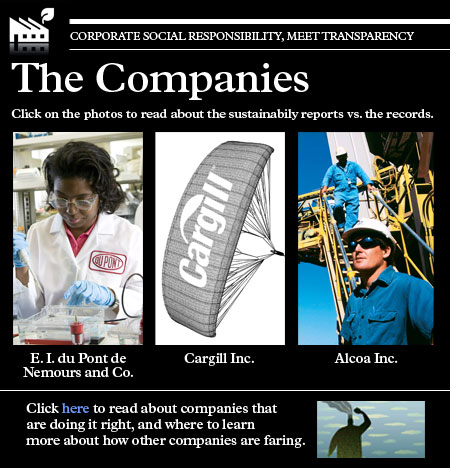

To illustrate the sometimes incomplete transparency of the glossy, full-color sustainability report, we examined the records of three venerable U.S. companies — Alcoa Inc., Cargill Inc. and E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Co. All three firms are formidable competitors and among the biggest players in their respective fields. Each has shown extraordinary dexterity, staying in business for more than a century (and in DuPont’s case, 209 years). And all three have sought the spotlight for their sustainability efforts with splashy and positive reports and advertising. These companies have not gone to the same pains to publicize the federal investigations they have attracted for environmental and other misdeeds. (See our reports on Alcoa, Cargill and du Pont for more details.)

The rosy outlook of many corporate sustainability reports doesn’t just aim at good public relations. Increasingly, it has a direct business function, because the financial markets now include measures of sustainability.

Dow Jones has a family of sustainability indexes, including the Dow Jones Sustainability North American Index and the Dow Jones Sustainability World Index. Other such ratings include KLD Global Sustainability Index, launched by Boston-based KLD Research & Analytics Inc. in 2007 “in response to the growing demand from institutional investors for global sustainability investment options” and the FTSE4Good Index, operated by a company jointly owned by The Financial Times and the London Stock Exchange. These new indexes lend prestige to companies that make the cut.

Meanwhile, financial media firms and stock market analysts have begun factoring environmental and social performance into corporate stock valuations. Some research even suggests that the companies embracing corporate responsibility outperform their competitors, says Joel Makower, chairman and executive editor of GreenBiz Group Inc., an online news service. “Companies certainly have the potential to change the social fabric,” says Makower, who thinks most corporations are “walking the walk” more than they get credit for.

“Some of the companies that are the most progressive are in the worst reputational binds” because of the difficulty of communicating their policies, he says. “Doing something less bad – those are hard stories to tell. You might reduce toxins in your product by 30 percent, but that leaves 70 percent that is bad. … Often when you talk about doing right, you illuminate problems.”

Others observers, however, fear all this reporting about and rating of supposedly well-behaved companies undermines support for government regulation that is needed, regardless of the progress of the corporate sustainability/responsibility movement. Aneel Karnani, a business professor at the University of Michigan, stirred uproar in corporate responsibility circles last year with an article in The Wall Street Journal that asserted: “In circumstances in which profits and social welfare are in direct opposition, an appeal to corporate social responsibility will almost always be ineffective, because executives are unlikely to act voluntarily in the public interest and against shareholder interests.”

In a recent phone interview, Karnani elaborated: “Let’s not delude ourselves; the only way to get companies to do something is to pass laws that force them to do it.”

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.