The renowned American-Indian writer, historian, theologian, professor and activist Vine Deloria Jr. once posed a question: “Did they ever think of asking the Indians?” Deloria was referring to the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, administered from the top down, like so many programs that have charted the course of Indian life in the United States. But he could have been talking about just about any encounter Indians have had with the federal government.

It’s surprising just how little is known — or understood — about American Indians beyond the Hollywood stereotype of noble savage and the sociological portrait of a people victimized. The continent’s first inhabitants have lived an almost unrecorded life. As their numbers have been diminished by conquest, epidemic, intermarriage and a host of social ills, a record of their history also has been put in peril.

But that process may be changing in Montana, where Julie Cajune, a teacher, curriculum designer and member of the Confederated Salish-Kootenai Tribe, is gathering the histories of Montana’s 12 recognized tribes as part of a groundbreaking initiative to include American Indians in the state’s history and the educational system that teaches it. The effort began when Montana became the first state in the nation to mandate the teaching of American-Indian history in its primary, middle and high school classrooms through passage — and finally, funding — of the Indian Education for All Act.

Teaching of Indian history to Montana schoolchildren has not been without controversy. One of Cajune’s early attempts to teach Indian culture ended amid a misunderstanding about a study of names that some took to be an Indian naming ceremony. They accused Cajune of “teaching spirituality” in the schools.

But Cajune knows that names can themselves be repositories of history. For example, the Salish word for Silver Bow Creek, which flows west from Butte to meet the Clark Fork River, is “The Place Where You Shot Fish In The Head.” The names depict two very different realities. Silver Bow Creek was likely named by miners in Butte. For decades, beginning around 1870, it was a repository of arsenic and mercury tailings from mining operations, resulting in the largest Superfund toxic-waste cleanup project in the nation, downstream near Missoula. For the Salish, it was a stream so full of fish, you could walk across it on their backs, Cajune says.

Indian names are important, she says, because they “speak to the people’s relationship to a place a long time ago. They often had to do with a natural resource found there or a particular event that happened there. From our frame of reference, these names are very old, and they speak to thousands of years of inhabitation in this geography, and that is something unique to our tribe.”

In 1972, during a state constitutional convention in Helena, two Indian students who were visiting the capital asked the framers to consider letting American Indians study their own culture — perhaps even their own language — in the public schools they attended.

A constitutional amendment was drafted and passed on a near-unanimous vote; it said “the state recognizes the distinct and unique cultural heritage of American Indians and is committed in its educational goals to the preservation of their cultural integrity.”

Almost nothing happened for more than two decades. For a time, the amendment’s intent was tied to Montana’s 1973 Indian Studies Law, which required that K-12 teachers living on or near reservations take a Native-American studies class. In 1979, that law was amended, relieving teachers of even that obligation.

After years of unsuccessful attempts to acknowledge the constitutional mandate, in 1999 a coalition of Indian legislators and other proponents pushed through the Indian Education for All Act. But the act still needed to be funded, and the state had consistently underfunded schools for years. In the late 1990s, a group of school districts sued the state over the inadequate funding, citing language in the 1972 constitution that required the state to provide a free, quality public education to all its students. Leaders of the group asked Carol Juneau, a teacher, a member of the Mandan-Hidatsa tribe and a respected state legislator, to support the school districts’ legal challenge. Her amicus brief contended the state had never met its commitment to preserve Indian cultural integrity.

In 2004, a state district judge agreed, and the Montana Supreme Court eventually followed suit. Seeing the writing on the wall, the Montana Legislature got on board in 2005, passing significant increases in funding for state schools and designating $7 million for Indian Education for All. Gov. Brian Schweitzer earmarked another $2 million for the gathering of tribal histories.

Julie Cajune was not the most likely candidate to be at the center of the nation’s first attempt to bring Indian history into the mainstream. In her early years at a Catholic school on her reservation, Ursuline nuns provided an education steeped in literature, plays and music; they had high expectations for the students. But in the public middle school in Ronan and a high school in Missoula, where her mother moved to attend the University of Montana, she felt firsthand the marginalization — and at times racism — Indians commonly experienced in the 1960s and ’70s. She dropped out of high school in her junior year.

Cajune finished her secondary education by passing a general equivalency exam and entered the University of Montana the next year, but she attended for just a year before marrying, moving to Oregon and giving birth to two children. After a divorce and return to the reservation, her experience in public schools led her to home-school her own children. From that grew an interest in teaching as a career. She enrolled in University of Montana-Western in Dillon and graduated in 1990.

Fresh out of college, she was recruited by a principal on the Flathead Reservation in western Montana — the home of her tribe, the Confederated Salish-Kootenai — to teach Salish language and history to first-through-fourth-graders at the area’s public school, Ronan Elementary.

Cajune’s foray into teaching Indian culture was fraught with challenges. She taught 400 students in eight classes in an eight-day rotation. For more than a year, no classroom was available, so she taught in a hallway. There were no curriculum materials, so she gathered her own, relying on tribal elders when her own knowledge was insufficient.

“When you start to teach, you find out, ‘What do I really know about this?'” Cajune explains. “I had to face my own lack of knowledge. I was learning simultaneously with my students. I found the people in my community who were generous and kind and were willing to spend time with me.”

Opposition to the teaching of Indian culture in the mainstream emerged early. The Flathead reservation is one of many Indian reservations in Montana that were opened up to homesteading in the early part of the 20th century, resulting in a checkerboard pattern of land ownership. Today, about 38 percent of the reservation is owned privately or held by the state or federal government; schools have roughly equal numbers of Indians and non-Indians, and conflicts inevitably arise. Cajune’s Indian culture classes ended after three years, in part because Cajune attempted to incorporate the study of names — a name’s language of origin, who students were named for, nicknames and multicultural practices of name-giving — into her classes. People concerned about the very idea of the class decided Cajune was teaching “spirituality,” and a local journalist labeled a celebration of names held at the end of the learning exercise an Indian “naming ceremony.”

Cajune says the controversy never completely abated, and the principal who had cajoled her into teaching was removed from her position; within three years, the class was gone.

Still, she had been the first to attempt this multicultural approach to teaching Indian history and culture, and she had learned as much as she had taught. In 1994, she earned a master’s degree in bilingual education from Montana State University, Billings, and went on to work for several years for the Confederated Salish-Kootenai tribes as a curriculum specialist, as an adviser and field services director in distance education for the Salish Kootenai College in Ronan, and then again for the Ronan school as its Indian Education director.

Passing the Indian Education for All Act and then getting it funded were vital first steps, but in 2005 the state still was far from realizing its goal. Histories of Montana’s recognized tribes had to be gathered and made accessible to teachers. That gathering of knowledge would not be easy. There is no one-size-fits-all Indian. Each tribe has a different language, a different history and a different worldview. Many of Montana’s Indian tribes still rely on an oral tradition to preserve their culture. Some had written histories, but even those were often related to one chief or one period of time. And very little was available in a form that could be used in schools.

Soon after funding was available, the Montana Office of Public Instruction decided to give the state’s seven tribal colleges the task of gathering the histories of the tribes, which would then be given to Cajune, who would put them in a form accessible to the state’s K-12 teachers. When history is passed down through generations of stories and teachings, there comes a time when the threads of memory wear thin, the fabric of language and culture fade. Many of the tribes had persisted for 500 years or more, but had only a few elders who still were fluent in the tribal language.

And there are secrets and place names known only to elders. An example of a secret held for years: Chief Spotted Wolf was a Northern Cheyenne war chief at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, where Gen. George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Calvary perished. But knowledge of the chief’s role had been closely guarded. His son would have lost his job with the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs if it became known he was a descendant of the chief. Only recently did Bisco Spotted Wolf, an elder in the tribe and Chief Spotted Wolf’s grandson, explain the connection in an article published in the Missoulian newspaper.

Names of places are also salient elements of Indian history. For example, Cajune explains, “The Place Where You Surround Something” refers to the area around St. Ignatius and a Salish hunting tactic of building a temporary corral and chasing deer or elk herds inside. The name at once connotes a place and a method for harvesting food. “River of Eyes Wide Open Wood” is named for a willow that grows prolifically on the banks of what is now called the Musselshell River. “When you strip the bark, knots in the wood look literally like eyes,” Cajune notes.

The tribal history project has asked elders to publicly share these names and other knowledge that has been guarded for generations. They will then be used with information gathered from a variety of other sources.

The history of each tribe begins with a creation story. Many of the tribes’ histories also include tales of migration. For instance, the Northern Cheyenne tribe once had a fishing culture and lived around the Great Lakes. The tribe migrated to Montana over the course of several hundred years, arriving in the 1800s. Like several other tribes, they came in search of buffalo, for centuries a main food source as well as a spiritual emblem. The first white settlers arrived in the state in the 1860s, and by 1890 six of Montana’s seven Indian reservations had been established. During this time epidemics wiped out up to 50 percent of some tribes’ populations, and broken treaties left Indians with a fraction of their original homelands. For instance, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 identified 38 million acres as Crow tribal lands; by 1905, the Crow Reservation had been reduced to 2.2 million acres.

In the early part of the 20th century, the reservations themselves were broken up in another federal initiative — the allotment system wherein tribes were forced to divide their land into a checkerboard of plots. Plots were first allotted to tribal members, and much of the rest of the land was opened up to homesteading. This period saw Indian land shrinking by 90 million acres. Relocation policies further weakened tribal bonds. In the 1960s, Indians were given one-way tickets to relocate to cities where it was thought they would assimilate better into the American culture.

Contemporary Indian history can be a bitter pill to swallow. But Cajune’s approach has been to place it in the broader but much shorter histories of Montana and the United States. For instance, the civil rights movement of the 1960s ignited an Indian consciousness and activism then, just as today’s inauguration of the nation’s first black president is feeding awareness and desire for a more multicultural view of the world.

Both periods are included in a timeline Cajune has created that shows each tribe’s history juxtaposed against key events in state and national history. Each school in the state will receive the timeline, along with a resource guide for teachers, model lessons and a list of primary source materials.

The Indian history curriculum will address a key tenet of governance that many people in the wider culture do not understand: Each Indian tribe is considered a nation and a sovereign power. State governments have no jurisdiction over tribes. Tribal nations relate directly with the federal government. Those facts are fodder for many educational opportunities that, Cajune notes, high school students are eager to explore.

In her curriculum materials, Cajune refers teachers to primary sources whenever possible. An example: Beginning in 1873 and continuing for decades, many Montana Indian children were taken from their families and placed in Catholic boarding schools, part of the federal government’s policy of assimilation. Many of the boarding schools ran on the labor of the children. Children were not allowed to speak their language; their hair was cut short on arrival and the rest of their culture was similarly stripped from them. Instead of having teachers explain the Catholic school period, she suggests that students read the journal of a young Indian girl written while living at one of the schools.

Similarly, Cajune’s curriculum for Indian education in Montana suggests speeches by Richard Nixon and Lyndon Johnson be used to demonstrate a growing national awareness of the need to address long-held biases, abuses and neglect suffered by Indian people — and to introduce students to legislation passed in the 1970s that began to address those issues.

As you travel north of Missoula on U.S. 93, a large sign announces when you enter the Flathead Reservation. Soon smaller signs are providing both the English and Salish names for creeks, a nature preserve, a bison range and the Mission Mountains, which rise above the rolling highway, their snow-covered peaks carving into a turquoise sky. The communities here are rural, but they contain a surprising diversity of people. Besides the Salish-Kootenai, Indians from many other tribes live on this 1.3-million-acre reservation, not to mention the descendants of early white homesteaders and the inevitable newcomers, including an Amish colony and the Montana Buddhist Center.

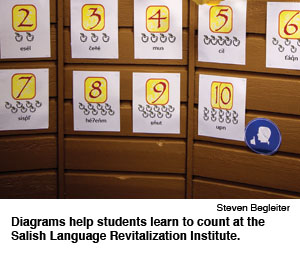

The Nkwusm Salish Language Immersion School is on the outskirts of Arlee, about a half-hour from Missoula. Raven-haired preschool children are being escorted by their parents from a monolithic concrete building that once housed a casino and bowling alley. It’s just 9 a.m., but they’ve already had their session for the day. Inside, 32 older students attend three classes, each led by a teacher and an elder fluent in the Salish language. Although a general curriculum is taught, this is a language school and, with only 52 Salish speakers still living, insurance against the disappearance of a language and a culture.

As she nears the end of two years’ work in gathering tribal histories, Cajune has taken a position as a fundraiser for the school. It’s a brisk February morning; Cajune has just returned from the inauguration of President Barack Obama, and she is brimming with excitement and stories, at once exultant about the outcome of the first stage of the Indian education project and aware that the real work has just begun.

Cajune would like to see the state’s colleges become more involved in Indian education, noting that the constitutional amendment was not just aimed at K-12. On that score, she sees a need for the inclusion of Indian culture and history in many disciplines — not just in Native American studies classes. For instance, should there be a class on American Indian literature, or should works by American Indians be part of an American literature class? Should there be a class on Montana Indian history, or should that history be taught as part of Montana history? Cajune believes in the latter, in both cases.

For American Indians to join the mainstream educational community, Cajune says, they will need to be willing to share their culture. She hopes that groups of people who know their tribes’ stories, languages and traditions — and are willing to explain them — can be formed. Success in Montana could have wide impact. Already educators and lawmakers in South Dakota and Washington state are considering integrating Indian history in their curricula and are studying Montana’s approach.

A cloud moves across her face as Cajune contemplates the next steps in a far-reaching undertaking that began more than three decades ago, when two students asked that they be allowed to study their peoples’ history in school. Before long, the sun pokes through, and she notes that it has been extraordinary to be “writing history and making it at the same time.”

“Do you see how far we’ve come?” she says in a statement that comes naturally to a teacher — at once posing a question and answering it.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.