Every year, thousands of high school students get ready for the SAT by using the Princeton Review’s test preparation services.

But few, if any, realize that the prices for the Princeton Review’s online SAT tutoring packages vary substantially depending on where customers live. If they type some ZIP codes into the company’s website, they are offered the Princeton Review’s Premier course for as little as $6,600. For other ZIP codes, the same course costs as much as $8,400.

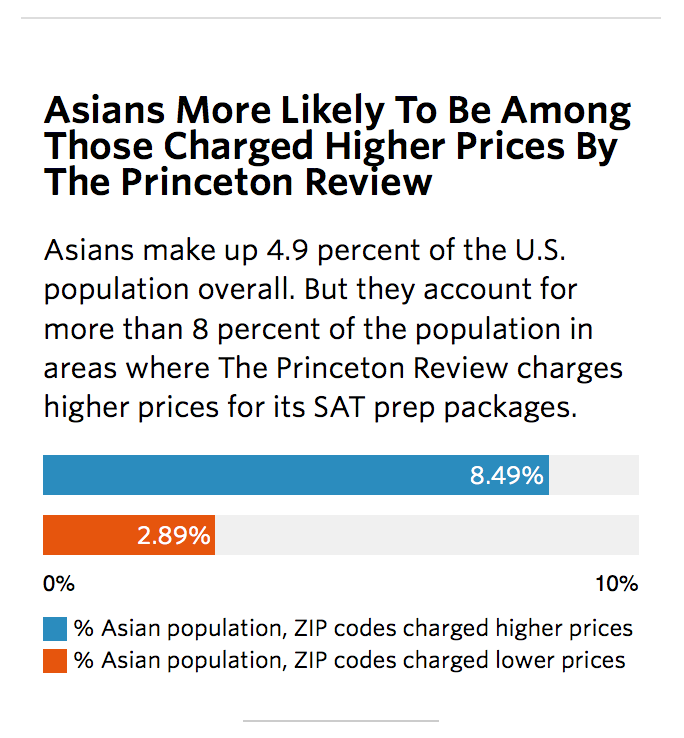

One unexpected effect of the company’s geographic approach to pricing is that Asians are almost twice as likely to be offered a higher price than non-Asians, an analysis by ProPublica shows.

The gap remains even for Asians in lower-income neighborhoods. Consider a ZIP code in Flushing, a neighborhood in Queens, New York. Asians make up 70.5 percent of the population in this ZIP code. According to the United States Census, the median household income in the ZIP code, $41,884, is lower than most, yet the Princeton Review customers there are quoted the highest price.

The Princeton Review said in a statement that its pricing is based on the “costs of running our business and the competitive attributes of the given market,” and that the company charges the same price everywhere in New York City. Although the test prep service markets its service as “24-hr Online Tutoring,” the company says the tutoring is done in one-on-one sessions in person or online and that the tutors typically live in the same areas as their students.

“The areas that experience higher prices will also have a disproportionately higher population of members of the financial services industry, people who tend to vote Democratic, journalists and any other group that is more heavily concentrated in areas like New York City,” the Princeton Review’s statement said.

These types of price differences are not illegal, and the consequences are not intentional, but researchers say they are likely to become more common in the age of services like Uber, which set prices by computer algorithms. The Princeton Review says its prices are simply determined by geographic region.

Last year, a White House report on “Big Data” cautioned that the “algorithmic decisions raise the specter of ‘redlining’ in the digital economy – the potential to discriminate against the most vulnerable classes of our society under the guise of neutral algorithms.”

In 2012, the Wall Street Journal reported that the online office retailer Staples was varying prices by ZIP code. Staples appeared to be calculating prices based on the user’s distance from a rival store, but the inadvertent effect was that people in lower-income ZIP codes saw the higher prices.

In 2014, researchers at Northeastern University found that top websites, such as Home Depot, Orbitz, and Travelocity, were steering some users toward more expensive products. And this year, another study found that users who were identified by Google as female received fewer ads for a high-paying job.

Offline, the practice of offering different prices for the same product in different places is fairly common—gasoline or a gallon of milk can be priced differently just a few blocks apart. But as long as there is no intent to racially discriminate, it is generally legal, says Andrew Selbst, an attorney who co-authored a paper on the biases that can be inherent in Big Data.

“If you are open for business, you can’t discriminate against certain protected classes,” Selbst said.

Unintentional racial discrimination is illegal in housing and employment under the legal doctrine known as “disparate impact,” which prohibits inadvertent actions that hurt people in a protected class.

But the disparate impact doctrine does not apply to the online world, where it’s often difficult to determine how and why different prices are being offered.

Earlier this year, Harvard undergraduate Christian Haigh stumbled on the Princeton Review’s variable prices doing research for a class he was taking called “Data Science to Save the World.”

Haigh had been looking for price differences in hotel rooms if he booked from different locations around the world. But he wasn’t finding much. So he looked for websites that required entering a ZIP code.

“We thought maybe if you have to put in the ZIP code, they were trying to discriminate,” Haigh said. Now, Haigh and three fellow students are publishing their findings that the Princeton Review’s higher prices correlate to areas with higher income.

ProPublica reviewed the code that one of Haigh’s fellow students posted on a public website and collected its own data in July, and again last week. The data showed that the Princeton Review offered four different prices for the same “Premier Level” online tutoring package.

Many of the prices are regional. For instance, the entire New York City area, including Long Island, receives the highest possible price, $8,400. Much of California, except San Diego, is offered the second-highest price, $7,200, while ZIP codes in San Diego are charged the lowest price.

Because the pricing regions are large, sometimes spanning multiple states, they are different than the personalized tech algorithms used by some websites, which make real-time decisions about which advertisements to show to a particular visitor.

ProPublica tested whether the Princeton Review prices were tied to different characteristics of each ZIP code, including income, race, and education level. When it came to getting the highest prices, living in a ZIP code with a high median income or a large Asian population seemed to make the greatest difference.

The analysis showed that higher-income areas are twice as likely to receive higher prices than the general population. For example, wealthy suburbs of Washington, D.C., are charged higher prices. But that isn’t always the case: Residents of affluent neighborhoods in Dallas are charged the lowest price, $6,600.

Customers in areas with a high density of Asian residents were 1.8 times as likely to be offered higher prices, regardless of income. For instance, residents of the gritty industrial city of Westminster, California, which is half Asian with a median income below most, were charged the second-highest price for the Premier tutoring service.

The Princeton Review said it would be a mistake to call its pricing practices discrimination. “To equate the incidental differences in impact that occur from this type of geographic based pricing that pervades all American commerce with discrimination misconstrues both the literal, legal and moral meaning of the word,” the company said in its statement.

The company said the prices of its online tutoring services are based on the prices of local tutors, which vary “just as virtually every good or service does, be it gasoline, rent or eggs.”

Even if the price differences were unintentional, the Harvard students said they found them disturbing. Haigh, the student who discovered the variations, is an economics major and said he’s not generally against price differences unless particular demographic groups are affected.

“It’s something that makes a very small impact on one individual’s life but can make a big impact to large groups,” Haigh said.

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “The Tiger Mom Tax: Asians Are Nearly Twice as Likely to Get a Higher Price From Princeton Review” and is re-published here under a Creative Commons license.