Global greenhouse gas emissions are on the rise, and the world is farther than ever from reaching the goals of the Paris Agreement, according to a new United Nations report, released just days before officials and climate experts from around the world will meet in Katowice, Poland, for another round of climate negotiations.

Three years ago at the climate negotiations in Paris, every country agreed to bring down its greenhouse gas emissions enough to keep warming below 2 degrees Celsius, and below 1.5 degrees if possible. A dire report from the U.N.’s top climate panel released earlier this fall found that the extra 0.5 degrees of warming would have drastic and disastrous effects on the environment—providing more empirical support for those countries pushing for more ambitious targets during the negotiations at COP24. But to keep temperature increases below 1.5 degrees, global emissions need to peak by 2020.

Between 2014 and 2016, global emissions remained relatively flat, giving negotiators hope that the decades-long trend of rising emissions was about to reverse. But after three years of stagnation, global carbon dioxide emissions rose again in 2017, reaching a record high of 53.4 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent. To meet the 1.5-degree target, the world needs to collectively bring emissions down by more than half in the next 12 years.

Countries’ current climate pledges put the world on track to miss that target by a wide margin—as much as 32 GtCO2e.

(Chart: United Nations Environment Program)

That the world’s NDCs are not sufficient is not news to anyone: Previous Emissions Gap Reports showed that we’re on track for more than 3 degrees Celsius of warming by 2100. Still, the Paris Agreement included a mechanism to increase ambition over time: Every five years, each nation will submit new climate pledges, and the international accord mandates that these new pledges must “represent a progression” beyond a country’s current NDC, and “reflect its highest possible ambition.”

But enhanced ambition is worthless without meaningful action, and several countries are falling short on their climate commitments already.

United States

The U.S., which accounts for more than 13 percent of global emissions, initially pledged to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025, but the country’s brief stature as a climate leader has crumbled under President Donald Trump’s administration. In 2017, Trump announced his intention to withdraw the U.S. from the Paris Agreement—a move that the country can’t formally make until 2020, thanks to a provision in the accord. In the meantime, his administration has sought to reinvigorate coal, stymie the solar industry with tariffs, and systematically dismantle the country’s climate legislation. Under Trump, the Environmental Protection Agency has sought to roll back the Clean Power Plan, revise fuel efficiency standards, and loosen methane rules, to name just a few.

The Climate Action Tracker, an independent coalition of European think tanks that track climate pledges, estimates that U.S. emissions will be around the equivalent of 400 metric tons of carbon dioxide higher by 2030 than was projected before Trump took office. That being said, if all the states, cities, and private corporations with climate pledges live up to their targets, the U.S. could still come “within striking distance” of its commitment, the Climate Action Tracker writes, by cutting emissions to between 17 and 24 percent below 2005 levels by 2025.

Brazil

Brazil, which accounts for 2.3 percent of global emissions, pledged to cut emissions by 43 percent below 2005 levels and eliminate illegal logging in the Amazon by 2030. Yet deforestation is once again rising in the region. The Brazilian government has slashed the budget of the authority charged with monitoring for deforestation, and paved the way for land grabs and further forest losses by easing land-use legislation.

Any optimism among climate observers that the country would still meet its climate goals was dashed by the election of Jair Bolsonaro of the far-right Social Liberal Party in October. Often likened to Trump for his appeals to nationalist movements, Bolsano has threatened to withdraw from the Paris Agreement (though he recently said that Brazil will remain in the agreement as long as it doesn’t diminish the country’s control of resources such as the Amazon) and to open up for development various lands that are currently protected as environmental preserves or for indigenous communities. Bolsonaro has appointed as his top foreign diplomat a man named Ernesto Araújo, who calls climate science mere “dogma,” and claims that the rival political party in Brazil has “criminalized” red meat and oil.

Australia

Australia, a country responsible for 1.2 percent of global emissions, set an emissions reduction target of 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. But the Climate Action Tracker found that, given the country’s current policies, Australia’s emissions will “far exceed” that target come 2030. Its emissions are rising and projected to continue growing—and, much as in the U.S., the federal government continues to back coal-fired power, though state-level targets for renewable energy and emissions reductions are more ambitious than federal ones. Australia’s leadership, again paralleling the current U.S. administration, says that the nation will stop contributing to the Green Climate Fund, which provides developing countries with the necessary finance to adapt to a changing climate.

Who’s Exceeding Expectations?

Some countries are faring much better, however: Morocco, Argentina, and Indonesia have all already adopted more ambitious greenhouse gas reduction targets since the Paris Agreement came into force. Twenty-three countries, including the Marshall Islands, Fiji, Canada, and the United Kingdom, announced their intention over the summer to increase the ambition of their NDCs in 2020.

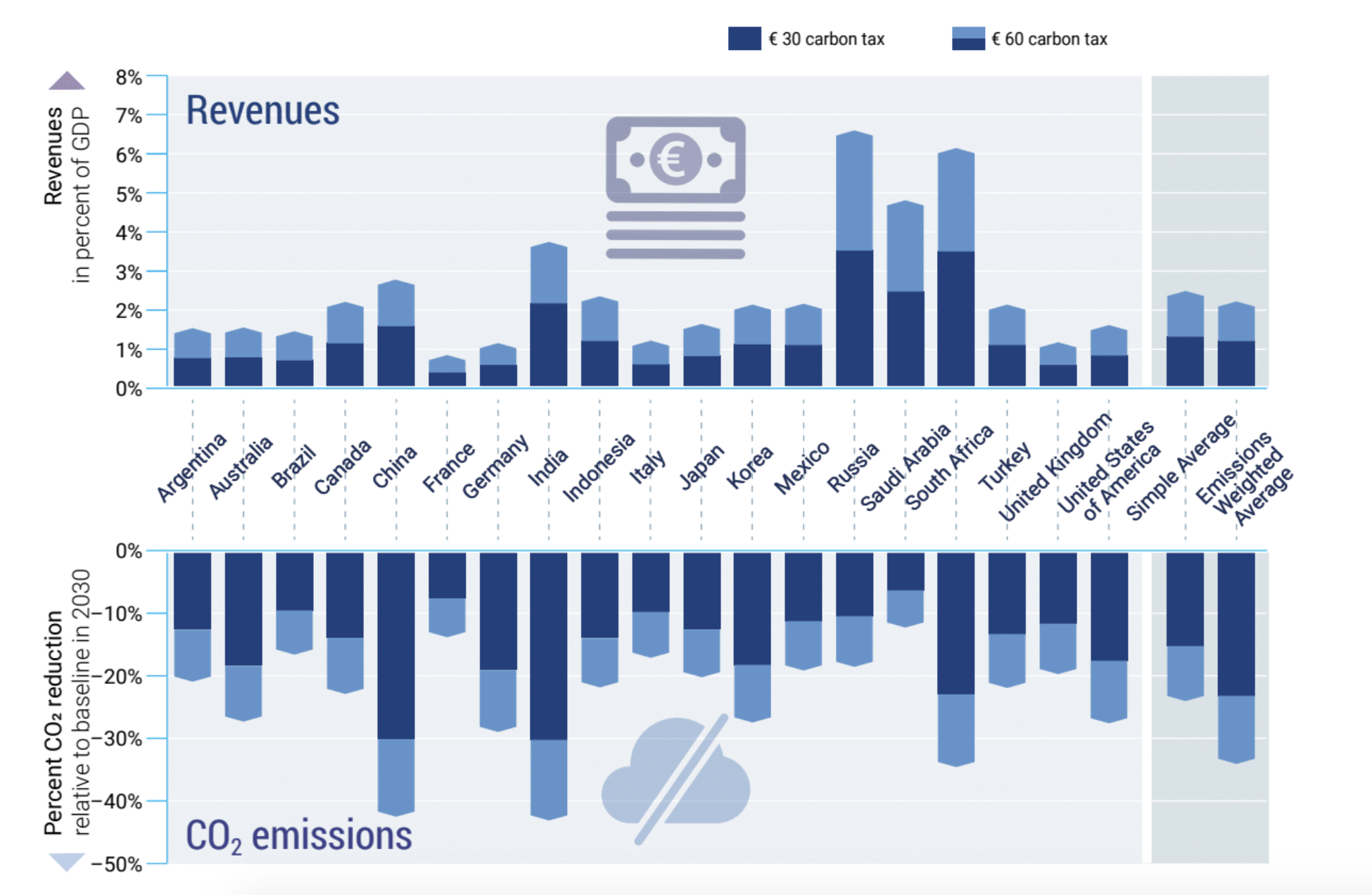

Beyond raising the bar with NDCs, the new Emissions Gap Report points to fiscal policies that could help bring down emissions in the meantime. Some 15 percent of global emissions are already covered by some type of carbon pricing scheme, whether a carbon tax or trading system. But, according to the report, prices are currently too low or inconsistent to make much of a difference. Still, reforming fiscal policies could have a large effect: A carbon tax of $70 per ton of carbon dioxide could lower emissions by anywhere between 10 and 40 percent, depending on the country. Ending fossil fuel subsidies would lead to another 10 percent reduction in global emissions by 2030.