Last week, a self-described Trump supporter left a lengthy voicemail for Francis Fukuyama. She was taking issue with his assertion that the “American people” are defined not by race or ethnicity, but rather by a shared belief in the principles upon which our nation was based.

“She was really upset,” recalled the Stanford University political scientist. “She said the Constitution says America belongs to the people who fought in the revolution, and their descendants. I suspect by ‘descendants,’ she actually meant ‘white people.'”

“At the end of her diatribe, she basically said I should go back to Japan, or wherever I came from. [Editor’s Note: He was born in Chicago.] I used to hear this sort of thing when I was a little kid, before the civil rights era. But over the last few years, that kind of rhetoric is crawling out of the woodwork more and more.”

Inadvertently, that woman was illustrating the main point of Fukuyama’s new book, Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Power of Resentment. To her, citizenship is tied to a specific ethnic identity, and she has internalized that group’s grievances.

Fukuyama argues this tendency to ground your sense of self in race, gender, or sexual orientation first took root on the left, often in reaction to genuine injustice, and has now spread to the right. No wonder our politics are so polarized: We all feel we’re being dissed, and we take it very personally.

In an interview from his Stanford University office on Monday, he discussed this increasing fragmentation, how it showed itself in the recent controversy over now-Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and how we could get to a shared identity as Americans.

In the wake of the Kavanaugh hearings, and his ultimate confirmation as a Supreme Court judge, are you more pessimistic about the future of American democracy?

Yes, I definitely am. I think what the hearings demonstrated is the fact that Americans are polarized in a very deep way. The people who watched Dr. Ford and said “I believe her,” and those who watched Kavanaugh and said “He’s a victim of the Democrats” were looking at exactly the same images, and hearing exactly the same words. But they interpreted them in dramatically different ways.

How you interpreted them depended upon your identity, and, increasingly, our identity is defined in partisan terms. If you have a certain set of beliefs, you must also [share the view of fellow partisans] regarding the veracity of a woman’s testimony.

There are fears that the new Supreme Court will implement a radical right-wing agenda that lacks popular support. Do you think that is likely?

If the court tries to dismantle what people consider settled law in a dramatic fashion, it’s going to produce a very big political controversy, in a way that will threaten the court’s legitimacy. But it seems to me [Chief Justice] John Roberts wants to protect its independence and integrity. The way he settled the Obamacare case [where he joined the liberal justices to uphold the legality of the Affordable Care Act] indicates he does not want to see the court politicized in that fashion. So it’s not inevitable that the court will move in a dramatic direction.

I recently spoke to a political scientist who argued the next Democratic president who has a Democratic Senate should immediately expand the Supreme Court from nine to 11 seats. Washington Post columnist E.J. Dionne made that same argument on Monday. Is that a good idea, or a dangerous one?

I think that would just inflame the partisan divide. I actually think this is a good opportunity to think about structural changes in the way we appoint justices. There are other reforms we need to think about before we go to that one. The first thing I would do is get rid of lifetime tenure [of justices]. That would dramatically reduce the stakes in these battles.

You could also formalize a lot of the procedures by which the prospective justices are vetted. Democrats are angry about the way Republicans used their control of the Judiciary Committee to cut short deliberations. You can write into law exactly how the committee needs to proceed in future cases. You could also write into law that the Senate has to consider a nomination within six months. That would make what the Republicans did to Merrick Garland [a President Barack Obama nominee who was denied a hearing for nearly a year] illegal.

Should that be a priority for congressional Democrats?

It would be perfectly legitimate. But the Democrats are going to have a long to-do list as they write into hard law the norms Donald Trump has violated. For instance, there’s no reason why the president should be the only federal official exempted from all these conflict-of-interest laws. That doesn’t make any sense to me.

You could also pass a law requiring presidential candidates to release their tax returns.

I actually think that’s going to happen, one way or another. I don’t see how the Republicans can resist an effort to turn that into law.

Kavanaugh was nominated by a president who lost the popular vote, and confirmed by senators who represent around 44 percent of the population. This is increasing popular awareness of the undemocratic nature of the Senate and the Electoral College. Do we need to make some fundamental changes in how we elect our president and representatives?

A few political scientists have run the numbers to predict what’s going to happen in the next few presidential elections, given the country’s demographic shifts. There’s a significant possibility that the Republicans will continue to hold onto the presidency, as the Democrats keep winning the popular vote. It’s happened twice in the past two decades. I think if this goes on and becomes a regular pattern, it will lead to a big crisis.

Changing the Electoral College and the Senate will require changing the Constitution, and that’s very difficult, especially at this moment of extreme polarization. That means we are building toward a slow explosion. I don’t think it will come right away, but if we have an election in which the Democrat wins the popular vote by an even bigger margin but loses the presidency, that will produce a big crisis, and I have no idea how it’s going to be resolved.

New York Times columnist Tom Friedman is warning of the possibility of a second Civil War. Is that overstated?

Yes, that’s overstated. But people could start resorting to violence. They’ll certainly be out in the streets, and things can get ugly really quickly.

You argue in your book that our current polarization is, at least in part, due to the rise of “identity politics.” Do you see the Kavanaugh controversy in those terms?

I think the whole #MeToo movement is a textbook case of what I describe as “dignity politics.” It’s based on women feeling they have an inner dignity, based on their accomplishments and who they are as human beings. But they’re regarded by men as sexual objects, and not recognized for what they believe to be their true selves. They argue that male society has to adjust its norms.

I think that’s fundamentally just and necessary, but the right has now borrowed that framing from the left. A lot of people on the white-nationalist side say they are a victimized minority also.

If you’re a working-class white person in rural Kentucky who lost his job because the factory shut down, you haven’t been at the center of the cultural discussion in this country in your lifetime. People have gone from thinking they represent the median person in the American national identity to thinking of themselves as being despised by the opinion-makers and the cultural elite.

There is a very significant number of whites in this country whose driving motive is explicitly racial. They are panicked about no longer being the dominant racial group. But I don’t think that’s the whole story. There are a lot of people who have a legitimate claim to not being adequately recognized.

Aren’t those feelings of grievance, justified or not, being exploited by politicians as a way to get, or stay, in power?

Yes, and the worst offender is Trump himself. He’s the first racist president in my lifetime, and he has worked to drive wedges between people.

So how do we start to move beyond this divisiveness?

I make the point in my book that the Constitution doesn’t define who the “American people” are. Gradually, we worked our way toward an identity that is not based on race or ethnicity, but rather belief in the Constitution and the rule of law. I believe this idea of a “credal identity” is very important. We need to find ways to look at each other as fellow citizens in a democratic republic.

Polls suggest most Americans don’t have a good idea of our nation’s founding principles. Are schools doing a bad job teaching civics?

I think they’re doing a terrible job. There’s poll data that only around 20 percent of high school graduates can identify even one right in the Bill of Rights.

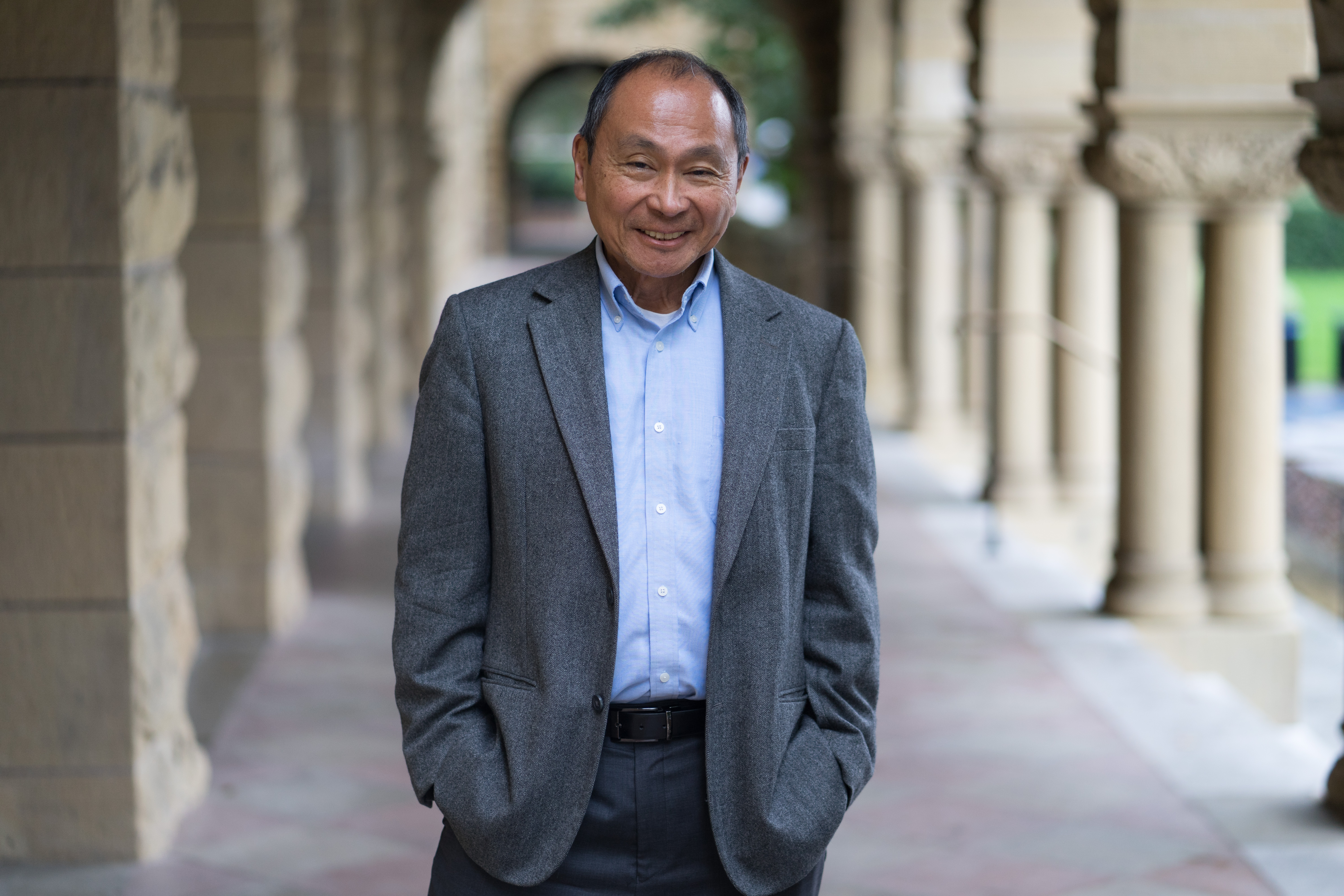

(Photo: Djurdja Padejski)

Do you see young people getting involved in politics now to a greater extent than they have in recent decades?

I’ve always been quite conscious of how few of my students wanted to go into politics. Now, a lot of them are. I think there’s a new realization that you can’t take these things for granted. But we’ll see. I think how many young people vote will determine the outcome of the election in November.

What do you think of the polls we read arguing that support for democracy has sunk to shockingly low levels among the young?

I’ve been following that quite closely. Since the original article [that made that claim], there have been some follow-up studies showing the decline in support for democracy is actually slight, and largely dependent on how you ask the question. A lot of people are unhappy with American democracy right now, including me. But that doesn’t imply they believe a military dictatorship, or some other form of authoritarian government, would be better.

The trend toward authoritarianism is not confined to the U.S. Brazilians are poised to elect an openly racist man with authoritarian tendencies as their new president.

That’s what started me on the project to write about identity. I think the whole world is shifting from the left-right economic divisions of the 20th century toward a politics that’s increasingly based on identity.

Narendra Modi, the Indian president, is basically trying to take a liberal national identity and make it a Hindu one. You have populist candidates in Europe who want to define national identity in ethnic terms. It’s a broad phenomenon, and it’s also leading to a populist leadership style, where politicians take a popular mandate and then use it to dismantle constitutional order.

On the other hand, the Quebec separatist movement virtually died last week after being soundly defeated in a major election. Does that indicate these identity-based fevers do break at some point?

It goes up and down, partly due to economic conditions. I don’t think it’s an inevitable trend. It’s a scenario where leadership can play a really big role. If you had a leader who didn’t want to opportunistically divide people on identity grounds, but rather spoke up in favor of a broader identity, that would do a lot to reverse these current trends.

In the end, we’re living in de facto multicultural societies. The only way you can do that peacefully is if you have a broad-minded sense of national purpose—one that makes all citizens feel they are part of a common enterprise. That’s what leaders do.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.