How do you respond to a terrifying natural and political disaster like Hurricane Maria? If you’re Aya de Leon, you write a feminist heist novel.

De Leon, who teaches at the University of California–Berkeley, started her career as a spoken-word artist. Since 2016, however, she’s been writing crime novels for Kensington Books, a publisher of popular romance and genre novels. She already had a contract for a novel for 2019; after the storm, she asked her publisher if she could completely alter the plot to deal directly with the storm and its aftermath.

“After the hurricane hit, folks on the island and Puerto Ricans in the diaspora, we were all sort of in shock,” de Leon says. “And I think a lot of us are just feeling really helpless and also kind of disconnected. I was thousands and thousands of miles away. People really wanted to do something. And I thought to myself, ‘The most impactful platform that I have in my life right now is that I’m writing these novels. And so let me take the next novel and make it about the hurricane.'”

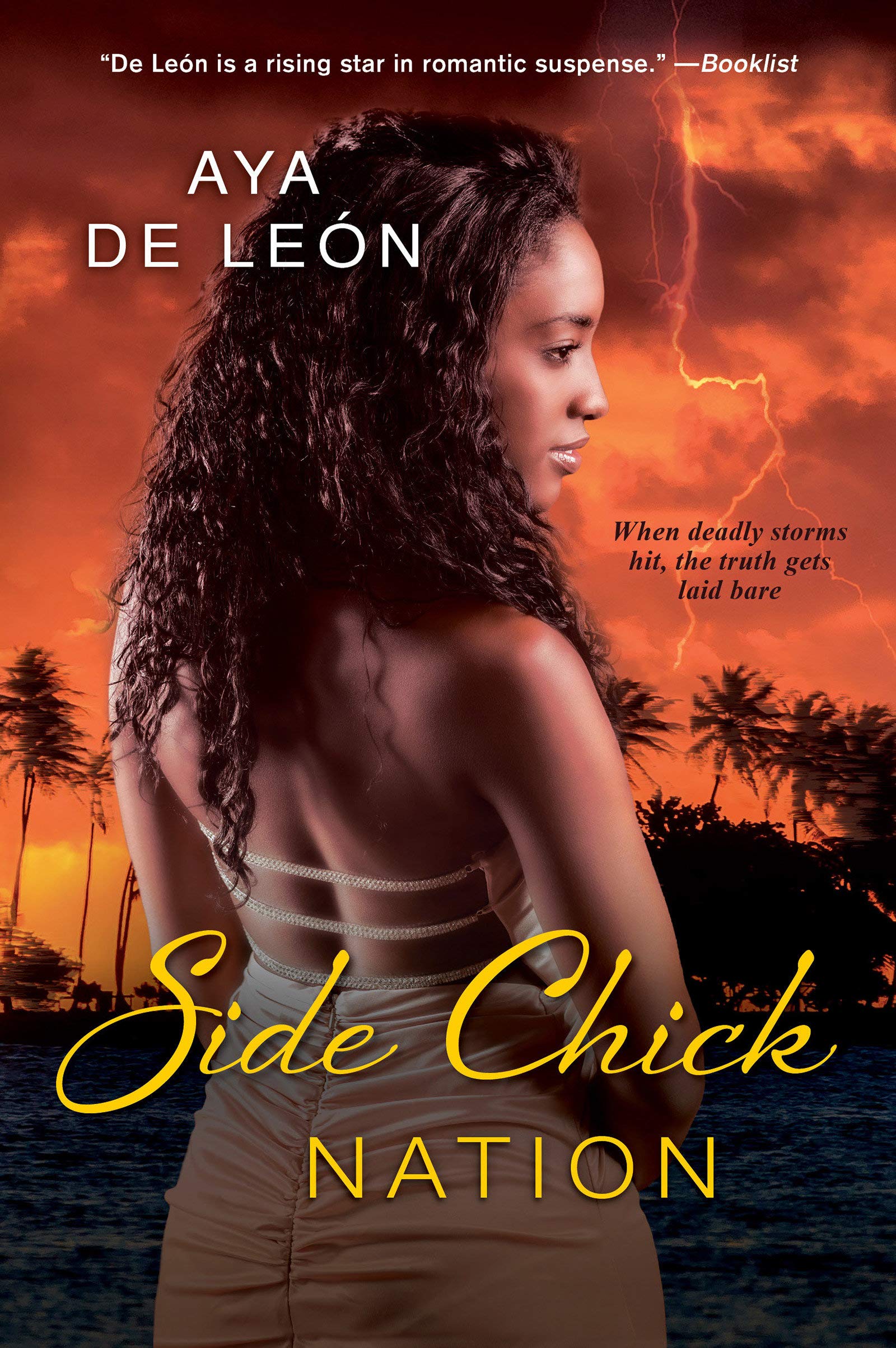

The result is Side Chick Nation, a story about Dulce Garcia, a Dominican-American sex worker who makes a living picking up a series of sugar daddies in Puerto Rico. After the storm warnings devastate tourism and ruin her business, though, she is unable to get off the island. She is left to dodge the floodwaters and struggle alongside the rest of the island’s population to find shelter, food, and clean water. Dulce’s experience as a “side chick” is a metaphor for Puerto Rico itself, which the United States cheerfully exploits in good times, and abandons when it is in need.

I talked to de Leon about Hurricane Maria and how she’s using pulp fiction to push for justice.

In the novel, you talk about how the relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico has been exploitative. What U.S. policies toward Puerto Rico need to change?

One of the demands is to cancel Puerto Rico’s debt.

The U.S.—not the Puerto Rican people or even their elected officials, but the U.S.—has selected this fiscal control board. It’s making all the decisions and imposing austerity measures that are just bleeding the island dry.

Puerto Ricans were given U.S. citizenship in order to be drafted for wars in the previous century. Because they’re citizens, Puerto Ricans can just go to the United States in tough times. So there’s this huge drain on the island. We’re left with a decreasing population and an increasingly poor population that’s supposed to be in a position to repay tens of billions of dollars.

(Photo: Dafina/Kensington Books)

So it’s just a horrible situation. But repealing the debt would be a start.

Side Chick Nation is the fourth book in your Justice Hustlers series of heist novels. Why is the heist genre a good venue for talking about feminism and social justice issues?

Heist is really exciting, because heist has the potential to be about social justice and wealth redistribution. So I developed this Robin Hood character, Marisol Rivera.

When you work at a non-profit, there’s this moment when people are sitting around, saying, “Oh my God, we need this much money, how are we going to make it happen?” And we’re like, “We should rob a bank.”

I’ve worked at many non-profits over the years, so in some ways, this series is about that fantasy come to life. [In the first novel in the series, Uptown Heist,] there’s a group of women who are running this health clinic serving low-income women in New York City. They ask, “God, how are we going to keep the doors open?” They end up with this opportunity to heist a group of corrupt corporate CEOs involved in a sex-trafficking scandal. They move from sex work, which is in this gray area in the law, and they move all the way over the line to burgling these corrupt guys.

Why did you decide to make sex work central to your novels?

The previous books of literary fiction that I had worked on didn’t have a lot of sex in them. I looked around in popular culture right now, and pop culture media is a lot more sexualized. I wanted to find a way to engage in that sexually highly charged media, but to keep the politics.

Sex work involves sex. But it’s also an exploration of gender, race, nation, capitalism. I thought, this is a way that I can have a series that has a lot of very politicized sexual content. And there are also lots of political fights going on that I wanted to highlight and support. Sex-worker characters are so frequently portrayed in a one-dimensional way.

I was writing about different women of color who are trying to figure out how to deal with the sexual objectification that comes with being a woman of color. People make different choices about it. But women in patriarchy have always at times said, “OK, if objectification is how women are treated, how do I work that to my advantage?” And [in my books], here is a community of women, many of whom have made that calculation, and sometimes it goes well and sometimes it goes horribly, and sometimes they’re exploited.

(Photo: Courtesy of Anna de Leon)

Have you talked to sex workers as you’ve been writing the series?

Absolutely. The first thing that I did when I started working on the series was reading work by sex workers about sex work. There’s a magazine, $pread, which was great. I basically got every single issue of it that I could get my hands on.

The second thing I did was go on social media to start building relationships with folks in the sex-worker community. And then I had different current and former sex workers read the books [before publication]—one of whom was an activist who totally took a hatchet to an early version of the first book. She was like, “This is a stereotype, this is a stereotype, this wouldn’t happen.” And I was so grateful. She really eviscerated my plot. She was like, “Nope.” And I was like, “Oh no, what am I gonna do?”

Yet the plot that I came up with instead was, of course, better. Getting that kind of feedback put me on a better path, and I feel like the book was so much stronger.

In a lot of ways, Side Chick Nation is more of a romance than a heist novel. In mainstream discussions, romance is sometimes portrayed as retrograde or anti-feminist. Why do you think it’s a good genre for advancing social justice?

Romance is the biggest-selling category of books. I want to talk to that mainstream demographic of women, and if this is what they’re reading, I’ll get in there.

The other thing that I will say is that one of the ways that racism manifests in communities of color is that it’s hard for us to have healthy relationships with each other. So there is something about having a story where people of color are fighting for justice in their communities and are also figuring out how to treat each other well in relationships that I’m really here for; even if at the same time there’s a lot about romance that is regressive, anti-feminist, or part of misogyny.

But there’s a lot of pushback within the romance genre, with different folks who identify as feminists, who are trying to push different narratives that have to do with love, sex, and relationships for women. I feel like I’m definitely part of that.

One of my favorite moments in the second book is that Tyesha—who is Marisol’s right-hand woman—her love interest in the second book, The Boss, is the rapper Thug Woofer. I asked myself what would break them up. And he’s a rapper, and she’s from Chicago, and I thought what would break them up is if he did an album with R. Kelly.

So I introduced this character who is not R. Kelly, but who has a similar profile to R. Kelly. And when [Woofer] announces that he’s doing an album with this performer, [Tyesha] completely loses it and cusses him out and walks out of his house, as far as she’s concerned never to see him again. So he has to figure out what happened, why she’s so mad.

The thing I realized that’s kind of my brand in my romances is that the thing that comes between the man and the woman in these stories really is patriarchy. There’s some way that the guy is participating in sexism that he can’t tell, and that that’s what breaks them up. And what brings them back together is that he comes back around, and decides that he’s going to be loyal to his partner as opposed to being invested in his privilege within patriarchy, or as opposed to seeing his partner through a patriarchal lens.

And I think that’s worth fighting for. I’m onboard.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.