In the United States today, there’s not a single county, metro area, or state where someone working a full-time minimum-wage job can afford rent on a two-bedroom home.

That’s the conclusion of a report published this week by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), a D.C.-based advocacy group.

NLIHC researchers also calculated region-specific housing wages—that is, estimates of the required earnings for a full-time worker to afford rent for a one- or two-bedroom apartment without spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing (the threshold above which the Department of Housing and Urban Development considers a worker to be “rent-burdened”). The research team found that, in 2018, the federal national housing wage was $22.10 for a two-bedroom rental, and $17.90 for a one-bedroom rental. In other words, a full-time worker making $7.25 per hour (the federal minimum wage) would need to work about 122 hours per week for all 52 weeks of the year—that amounts to three full-time jobs—in order to afford a two-bedroom rental, per the national fair market average.

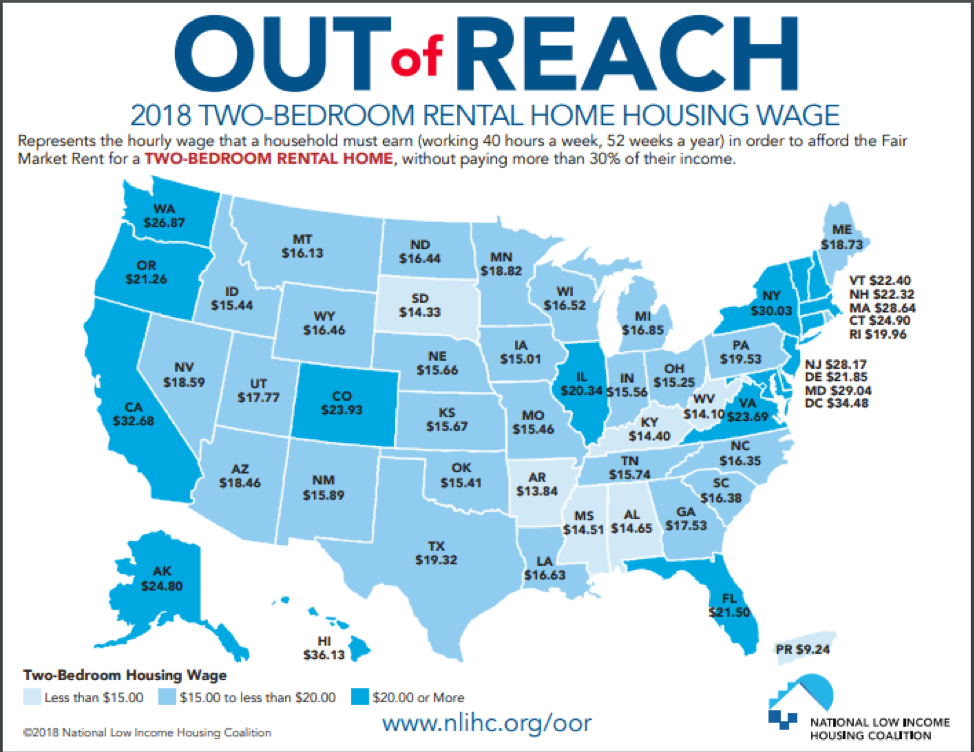

While minimum-wage renters are rent-burdened everywhere, there is substantial variation across the country, as the map below illustrates:

The housing wage in Arkansas, for example, is only $13.84. In Hawaii, by contrast, it’s $36.13. There’s also, of course, substantial variation across different metro areas. Not surprisingly, San Francisco ranks as the city with the highest housing wage in the country, $60.01. While cities like San Francisco have passed local minimum-wage hikes, those hikes are often woefully insufficient in the face of soaring housing costs. In 37 of the 38 areas that have a higher minimum wage than the federal minimum, a full-time minimum-wage worker still can’t afford a one-bedroom rental (and a minimum-wage worker can’t afford a two-bedroom in any of the 38 jurisdictions).

The NLIHC report highlights the convergence of three trends in recent years: inflation in the cost of housing; growth in low-wage occupations; and stagnant wages, particularly at the bottom of the income distribution. According to an analysis by Jenny Schuetz of the Brookings Institution, between 2000 and 2015, the percentage of income spent by the median renter in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution on rent increased by 11 percent. But it’s not just low-income renters. Higher-income folks are also spending a greater percentage of their income on rent.

“While the median monthly rent of low-income renters increased by $60, median monthly incomes fell by just over $100,” Schuetz concluded. “These renters are therefore getting squeezed by both declining incomes and rising rents, and finding that there is less money remaining for other expenses as a result.”

A Pew report published in April, meanwhile, concluded that the percentage of rent-burdened households increased by about 19 percent between 2001 and 2015 (to 38 percent of renter households).

This latest NLIHC research confirms that the problem is national, and affects even minimum-wage workers in areas with higher minimum wages. For those households, rent is a financial burden that no amount of full-time work can overcome.