Writing about climate change is often fraught, and hard to do beautifully. Because the ruling party refuses to acknowledge that the problem is real, writing on the subject often lapses into a didactic style of pose. At the same time, it can be easy to fall into a doom-saying pattern that focuses on scientific foreboding, technical but blunt language about our dire predicament. In this context, Elizabeth Rush’s Rising: Dispatches From the New American Shore is a revelation. The book is the story of Rush’s travels around the United States, visiting communities that are shrinking or disappearing because rising water levels have made them unsafe. Their stories, told through a combination of lyrical reportage and first-person accounts from her subjects, coalesce into a moving and urgent portrait.

The characters with whom Rush becomes most intimate are the members of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Native American tribe on Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana. Here, Chris Brunet, alongside his neighbors and former neighbors, have two chapters dedicated to them. One comes near the beginning and the other nearer to the end, and in a sense their stories shape the trajectory of the book. Louisiana is a sort of poster-state for the damage that rising sea levels can do. More so than any other state, the encroaching water has changed Louisiana’s shape dramatically, and the changes in the communities that Rush visits reflect this encroachment. The state lost almost 1,900 square miles of land between 1932 and 2000, and is on pace to lose more, faster. “Over the past 30 years,” Rush writes, “nearly 90 percent of islanders have moved inland.”

Rush writes that she has started to think of those who left the island as some of the country’s first climate refugees. There is a cruel irony in the way that their displacement affects both culture and climate. After Brunet tells Rush that, on his trips to Walmart, he often sees former islanders who have moved away, she seizes on the feedback loop that he and former residents are trapped in:

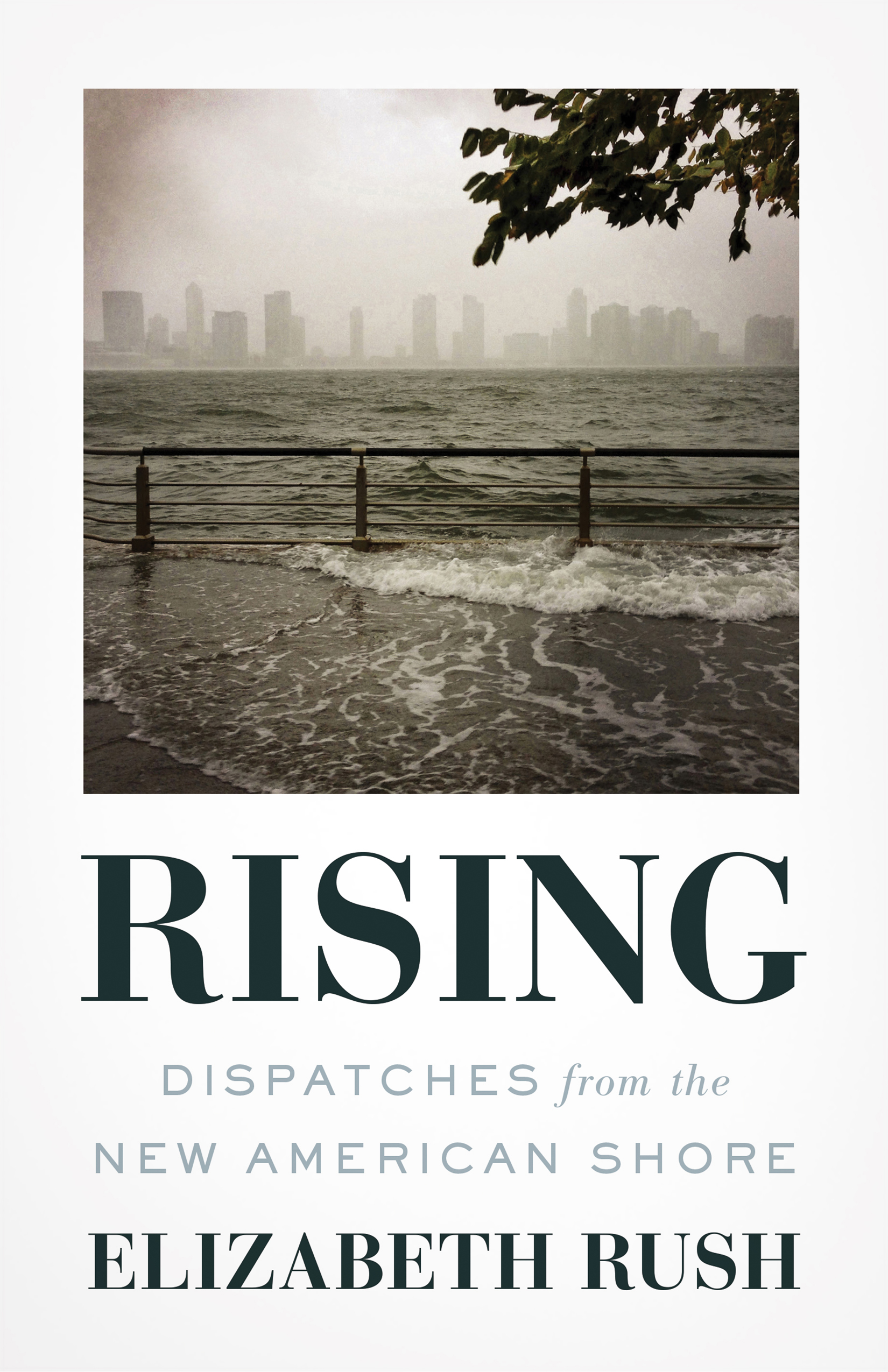

(Photo: Alvarez Ewens)

[T]he disappearance of coastal land is causing human beings who were once self-sufficient, whose impact on the planet was slight, to use fossil fuels to procure the foods they once were able to grow at home. Every time the islanders drive [out of town] they are, in some small way, accelerating the disappearance of this ecosystem.

Rush lets this thread end there, but it is one of the most striking in the book. On top of highlighting how climate change has forced people to participate in the systems that lead to their own uprooting, throughout the book, she continues to draw attention to a particularly insidious fact of the crisis: Some of the richest people in the world are making money off of displacement for which they are disproportionately to blame.

Rush’s writing about Staten Island, which focuses on the Oakwood Beach community during Hurricane Sandy and the recovery efforts afterward, offers a similar critique from a different direction. While she’s speaking with Alan Benimoff, a professor at the College of Staten Island, he shows her a map with 24 red dots. “I’ve plotted every single Sandy-related death,” he tells her. “The important thing to realize is this: Over half of the people who died in the storm were standing atop land that once was a tidal marsh. If you ask me, none of those homes should have been built in the first place.” Developers prized building and selling more homes over building and selling homes that were sensibly located and safe. Now, most of these houses have been razed. As part of the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, the federal government paid pre-storm prices for the homes and then “knock[ed] them all down so the land might act as a buffer in the next storm.”

Retreating is a not an easy choice for a community to make, and it is difficult to execute successfully because it requires near-unanimous participation. Those who are faced with the decision tend to be distrustful of the government, often because the government has given them good reason. An Oakwood Beach resident tells Rush that they’ve spent years trying to get the city to help prevent flooding—and when they finally did, installing a berm and promising that it would protect them, it got destroyed during the hurricane.

(Photo: Milkweed Editions)

On Isle de Jean Charles, Rush sees a pair of Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) representatives try to talk with a resident, Edison Dadar, who has thus far been uninterested in moving away. The deal, as Rush describes it, seems pretty good. The government has proposed a sizable chunk of money that they planned to use to relocate the community, which could keep the tribe together. But during the conversation, one of the HUD representatives says that, if they relocate the rest of the residents and he remains, the state won’t repair the roads that are wrecked during the next storm. Rush rightly notes that this pronouncement has the cadence of a threat, from the government and from the climate too. Of course, it is not just the officers themselves giving him pause. “Don’t come in here and take me and put me where you want,” Edison says to agents. “What am I going to do inland, watch TV and get old quick?”

This moment offers a crystallization of what makes it so difficult to help people who live under the threat of environmental catastrophe: If they are to survive, they must choose to leave behind the only place they’ve known. There is no good way out of that conundrum, and the question is not going away.

One place to begin, Rush’s book seems to suggest, is with empathy, not as a feeling but as a practice. Rush quotes a few passages from Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams—”Empathy means realizing no trauma has discrete edges. Trauma bleeds. Out of wounds and across boundaries,” for example—and evaluates her own words and actions with skepticism accordingly. In Pensacola Beach, Alvin Turner tells Rush about how he rebuilt after Hurricane Ivan, and how he still has yet to pay off his trailer in full. Rush writes:

I say, “I can’t imagine how difficult it must be for you.” By “it,” I mean all of it: winds unknotting the window frames and the rebuilding that followed; the death of his wife and the debt; the noticing for decades that his neighbors often lose everything when they flood, and that some just leave because they don’t have the money to rebuild or insure. By all of it, I mean not knowing when the next storm will come. I mean opening the door to my white face, with its passing fear; always being the one who is expected to welcome in outsiders seeking answers. I mean everything I can imagine and everything I can’t.

This is not just an exegesis of Rush’s thinking; it’s also a model for how the rest of us can begin the process of caring for and supporting those hit hardest by climate change. The project of Rising, like the project of Matthew Desmond’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, is to draw attention to ongoing material crisis through the stories of the people who are surviving within it. Rising is a clarion call. The idea isn’t merely that climate change is here and scary. There’s a more important message: There are people out here who need help.