In 2016, Lyz Lenz wrote an article for Pacific Standard called “The Death of the Midwestern Church,” examining how rural church closures had affected Midwestern communities. That article led to her new book, God Land: A Story of Faith, Loss, and Renewal in Middle America, which examines not just the impact of these church closures, but also the larger ways that Evangelical faith has shaped the culture and mentality of America’s heartland.

In God Land, we follow Lenz on two simultaneous journeys: We ride along as she travels around the Midwest to talk to pastors and churchgoers about their congregations and the roles they play in their communities—about faith as a touchstone of the American ideal; about the “good old days” that may or may not have ever existed. While she’s traveling to research this book, Lenz is also undergoing her own spiritual and personal reckoning, leaving behind a church where her voice had long gone unheard, and, in doing so, leaving behind her marriage.

The convergence of these two stories—Lenz’s personal journey to find a church where she could feel both embraced and heard, and everything she had to give up to get there; and her inquiry into how faith in America is changing—creates a micro and macro picture of what it feels like to lose faith, what keeps people coming back to church, and what it really means to have a voice in one’s community.

Lenz spoke with Pacific Standard to discuss writing a book about faith in the heartland while Donald Trump rose to power and her marriage collapsed.

I’m interested in the way you weave in your personal story, because it feels so central to the project, but I know it wasn’t originally part of your plan for this book. What made you realize you had to tell your own story too?

I really didn’t want to put it all in there. But key moments of my life falling apart kept happening in sync with these terrible news stories. There are so many books about religion that are like, “These are the religious movements in America.” But it’s different to see when it impacts a person. I wanted people to care, and I wanted people to see that this isn’t just grand theology or arguments over political policy. This is affecting people’s lives in a real way. And the only way I could do that was to just bleed all over the page.

(Photo: Pilsen Photo Co-op)

A big thread in the book that grows out of your personal story is the idea of women in ministry and women being able to have leadership roles in the church. What makes that so important to you?

There’s a huge problem with representation in the church, and it’s one of the last spaces that has really resisted any sort of gender equality. Not allowing women to have these roles is a way of silencing them. And when you silence women, you don’t hear their experiences and you have to trust men to “do what’s best.” And then you see sexual assault allegations being covered up.

And just on a smaller scale, you’re just not listened to, your perspective isn’t there. You do all this work and you’re not allowed to get a vote. I don’t believe it’s what faith is about. I don’t believe it’s what Jesus is about. I don’t believe it’s what any sort of good organization should be about, and yet it is the one space in America where people are totally fine with how it’s being run.

I’ve been in conversations where [the exclusion of women from ministry and church leadership] is justified with a lot of biblical talk. But two people can read the Bible and come away with completely different answers. One of the super-radical things about Martin Luther was that he was like, “Hey, anybody can talk to God,” which caused wars, and people died because he said anybody can talk to God. And we need to do that again. We need a new reformation, but this time we need women, we need LGBTQ people, and we need to start being more inclusive. Not just gender and sexuality, but also race. That’s a big problem.

And the idea that two people can read the Bible and come away with two totally different ideas, that’s kind of central to so much of what’s happening in this country right now, right?

There’s this conversation happening right now about the border where people will say, “Oh, if you actually believed in the Bible, you would help the women and children at the border.” And then the people on the other side are saying, “No, we do believe the Bible and we believe that we’re protecting America.” And so both sides are accusing the other of twisting the [Bible’s] words to justify their beliefs.

I wonder what would happen if we stopped taking an ancient literary text to justify every single little thing we do in America and just, like, had some conversations. I think that’s almost impossible because there is a huge portion of America that does use the Bible to justify everything that they do. But I also feel like getting into that battle is kind of a foolish fight, because we could go back and forth for days throwing Bible verses at each other and absolutely never get anywhere. And I don’t think that’s the fight where I want to be. The fight where I want to be is just doing the good things.

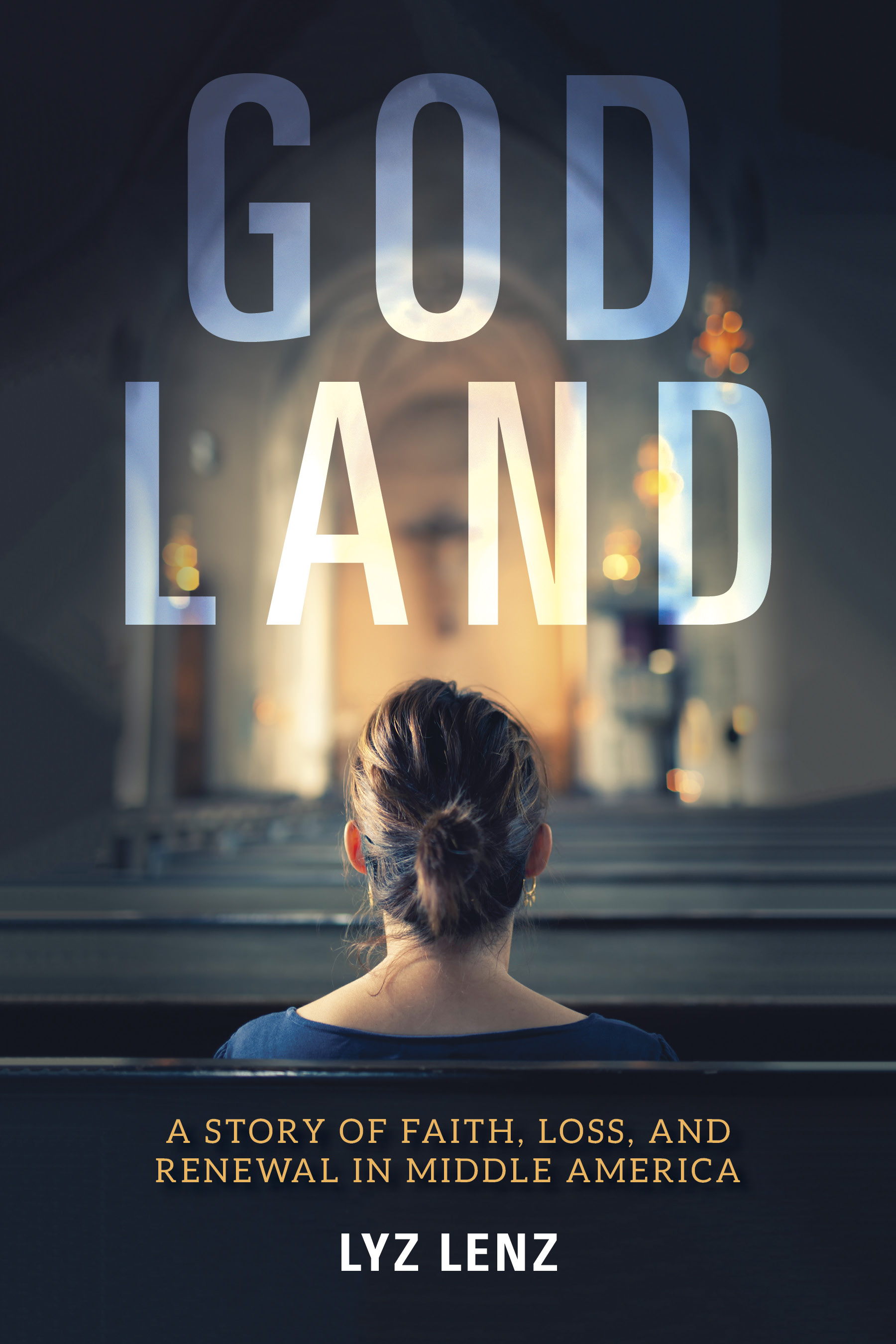

(Photo: Indiana University Press)

I went to a Lutheran college, and one of the first things that I had to do there was read Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and he does this thing where he wrestles with questions like: “Is murder good? Is it bad? Let me look at the Bible and decide.” And he does this whole thing where in the end he’s like: “Yeah, I could use this book and literally justify either side. How about I just do what I know I need to do.”

There’s this verse…. Oh my God, I’m going to quote a verse at you. I haven’t done it yet.

I’m ready.

There’s this verse I think about all the time and it’s basically, “To him who knows to do good and does not do it, to him it is sin.” I think the concept of sin is very theologically problematic to say the least. But I think the point of that is, like, if you know the right thing to do and you do not do it, what are you even here for?

I saw you post on Twitter that no interviewers had asked you about hot Jesus yet. So … talk to me about hot Jesus.

Oh, hot Jesus! I feel like if Christians would just have some sex, hot Jesus wouldn’t be so weird. It is just something I’ve always noticed and has always made me laugh. Like there’s this one modern worship song that I kind of love because of how super creepy it is—the chorus is like, “Make me, mold me, fill me, use me.” And I’m always like, “Wow, I’ve seen that porn, you don’t have to sing about it in a church service!” In Sunday school as a kid, you’re taught, “If you have sinful thoughts, just think about Jesus or like look on the cross.” What exactly is that supposed to accomplish except some sort of weird Jesus fetish, you know?

There’s a real problem with depictions of Jesus, right? They’re all white men who look a little bit like Brad Pitt, and, as we all know historically, Jesus did not look like that. He was black or Middle Eastern. He was Jewish. He wasn’t this American Corn-Fed God. And I just feel like maybe if we could all allow ourselves to embrace our bodies, have a little good sex, and then try to make a picture of Jesus, maybe he’d end up looking like a Middle-Eastern Steve Buscemi and we could all just be normal about this.

And I do seriously think it relates to this sublimation of physical desire and the separation of ourselves from our bodies, which is what Evangelical Christianity is all about. But in researching the book, one of the things I learned was that that’s not how faith has to be. There are Christian traditions that embrace the body and don’t see it as this shameful thing. You can orgasm and still love Jesus and it’s going to be fine.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Pacific Standard’s Ideas section is your destination for idea-driven features, voracious culture coverage, sharp opinion, and enlightening conversation. Help us shape our ongoing coverage by responding to a short reader survey.