(Photo: Crown/Tim Duggan Books/Henry Holt/Taylor Le)

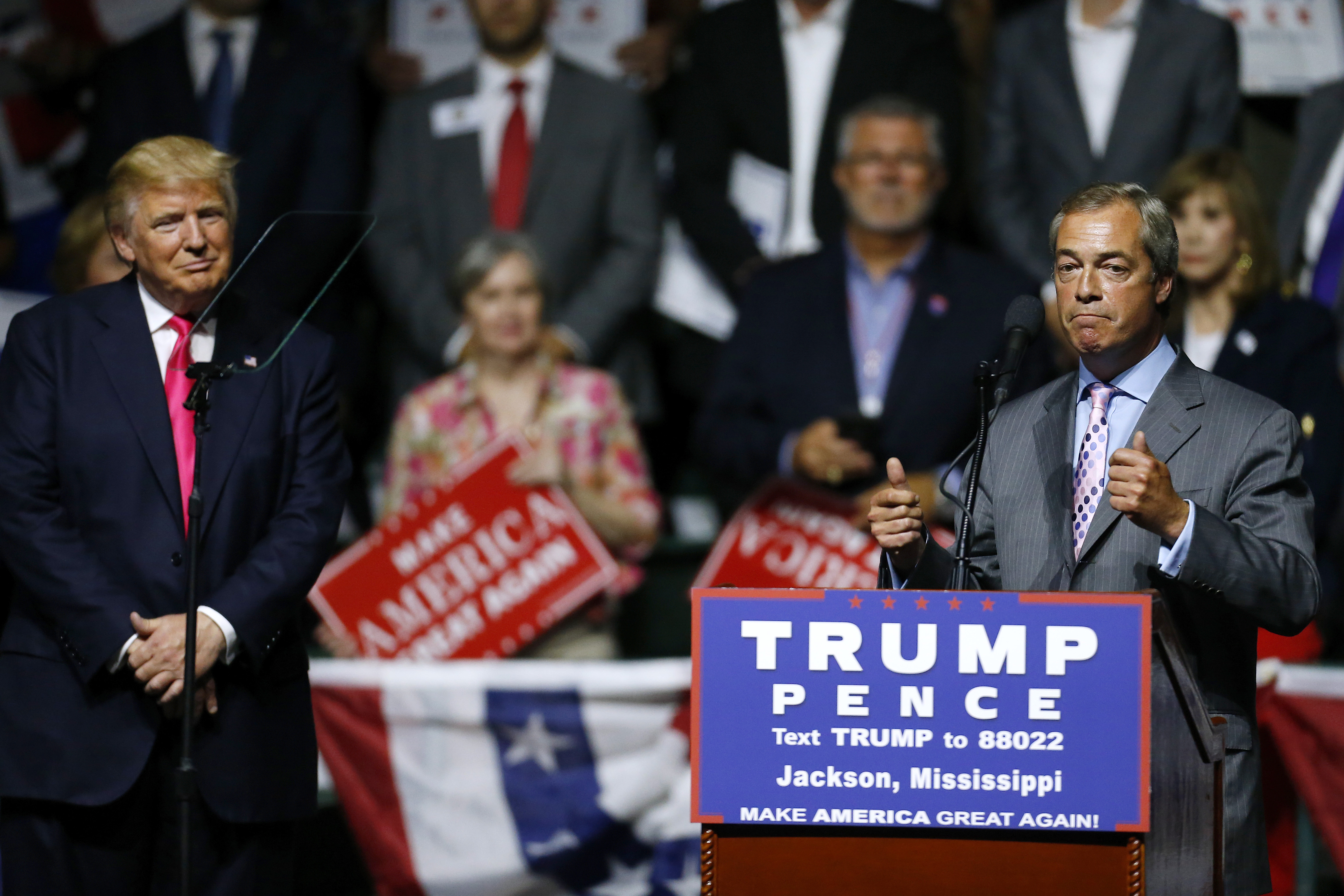

From the start, the Donald Trump administration has been a spectacle: The constant onslaught of tweets, executive orders, firings, investigations, and other noise has been circus-like. Trump might feel wholly new, but his authoritarian tendencies can be found in historical leaders around the world; more recently, his brand of rogue, outsider rhetoric has been utilized by leaders across Europe, including Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and Austria’s Sebastian Kurz. A clean line can be drawn through 2016’s Brexit and the election of Trump, and the 2017 European elections, in which centrists campaigned against far-right candidates.

In the past year and a half, there have been various attempts to mine the past for answers to the riddle of Trump, by applying thinkers like George Orwell and Hannah Arendt to our current situation, as we grasp at lessons for how to forestall authoritarianism. But to fully understand this moment requires more than a single central thesis. Three new books—How Democracies Die, The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America, and The Death of Democracy: Hitler’s Rise to Power—offer a way to contextualize the Trump administration theoretically, internationally, and historically. In fact, a complete picture is best formulated by reading them together. One book alone cannot summarize the history of white supremacy, misogyny, and shifting dynamics within the Republican Party, Russian interference on the international stage, and the psychology of political culture that makes many citizens amenable to authoritarian-style rulers. Reading these titles together illuminates many threads at once—and shifts the focus from Trump’s daily provocations to a more revealing examination of white aggrievement, economic indignities, and the other reasons leaders like Trump are able to gain a foothold in the first place.

The spectacle itself raises questions, most notably whether it is part of a concerted strategy to keep us off-kilter. If we see the spectacle not as a sign of ineptness (or rather not exclusively a sign of ineptness), we can understand it as a manifestation of what Timothy Snyder, in The Road to Unfreedom, calls “the politics of eternity,” by which he means a political program of destabilizing society through a planned and perpetual state of crisis, alongside rhetoric that leans on nostalgia for a mythic past that never was: “Make America Great Again.” Snyder’s main concern is Russia’s ambitions on the world stage, and the ways in which Russia’s tactics in Eastern Europe over the past 10 years can be seen as a precursor to its interference in the 2016 election. But he also draws on political trends in the United States and Europe, along with Russia’s ties to Brexit leaders and Trump officials, to paint a picture of political ideologies that are shifting globally in an authoritarian direction.

For Snyder’s study of the U.S., the shift from the politics of inevitability—that is, a rhetoric that creates a sense of nearly divine destiny—to the politics of eternity in right-wing strategies is an important focal point. As with Richard Nixon’s Southern Strategy of the late 1960s, “Make America Great Again” is an exhortation that links greatness to the past. As Snyder explains, leaders use this rhetorical cover to free themselves from having to provide a vision for future progress; this lack of vision, in turn, allows for the passage of policies that feed the crisis loop, disadvantage an ever-greater portion of the citizenry, and exacerbate tensions in order to make cross-community organizing more difficult. The Trumpian spectacle, from this angle, emerges as a strategy for creating a political culture amenable to such backward changes.

(Photo: Jonathan Bachman/Getty Images)

Snyder’s account is compelling, but his analysis of the Trump administration’s specific actions lacks depth; although beginning and ending with analysis of the U.S., the bulk of the book is given over to a close examination of the international aims of Vladimir Putin. Snyder spends less time discussing the effect that Russian efforts have had on countries like the United Kingdom and the U.S.; his analysis can feel overstretched at times, and there are dots that he doesn’t quite connect.

The scholarly How Democracies Die, by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, takes a comparative approach to understanding how the rhetoric, action, and ideology we’ve seen emerge in the U.S. since 2015 fit together, and their book as a result is thorough and well-argued. The authors link Trump’s actions to historical examples in Europe and Latin America, and they go beyond Trump’s personality to examine the remarkably central role of norms rather than written laws in maintaining democracy. Levitsky and Ziblatt’s most striking analysis can be found in their discussion of the abdication of authority by the GOP in the face of flagrant dismissal of those norms; by refusing to take bipartisan action to rein in the administration or hold the executive branch to expected standards of behavior, the authors argue, Republicans in Congress have paved the way for authoritarianism. Pointing to countries, such as Austria, where coalitions of opposition parties banded together to counter a demagogue’s rise to power, the authors make a compelling case that Republican inaction has been just as important a part of the rise of Trump as any efforts by his most unquestioning supporters.

But the biggest strength of How Democracies Die is its bluntness of language in describing American history—a bluntness that often goes missing when we discuss our own past—particularly when the authors examine the power of Jim Crow-era voting restrictions in creating what the authors call “literally one-party states” in the South. Levitsky and Ziblatt place Trump within a set of demagogues who could have been major leaders—Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, George Wallace—but were excluded by party apparatus. These earlier demagogues, much like Trump, were dismissive of democratic norms and used a rhetoric of violence (and often abject racism) that gained them significant and dedicated followings. Levitsky and Ziblatt don’t reserve their critique just for the right, though; they also single out Huey Long as an example of a Democratic populist who supported egalitarian social programs but also showed signs of potential authoritarian leanings. As Levitsky and Ziblatt demonstrate, these predecessors make it clear that Trump is not an anomaly; rather, he is the latest in a string of loudmouth leaders who have laid bare an ugly momentum in the American electorate.

Many scholars and commentators of late have sought to understand the rise of Trumpism through the lens of Nazi Germany. It’s an understandable impulse; like Adolf Hitler, Trump came to power on a wave of middle–class support that paradoxically endorsed autocracy by voting for it. But perhaps it’s more incumbent on us to clarify our account of how Hitler gained power in the first place, before we start drawing new conclusions about the autocrats of the present day.

In The Death of Democracy, Benjamin Carter Hett crafts a careful portrait of the Weimar Republic as a strong and diverse democracy, and describes how it succumbed to the rise of the Nazis. It’s a story many of us know in broad strokes already: Hitler was able to amass power through a combination of legal means and manipulation of entrenched anti-semitism and resentment over economic hardship. But Hett goes further, teasing out the divisions between the cosmopolitan elite of Berlin and the conservative rural communities who felt left behind by changing norms. Partisan divisions exacerbated by the connection of group identity to political allegiances—or “confessional divisions,” as Hett calls them—created a sense of loyalty to certain parties or blocks. Voters who belonged to a particular faith or community showed an inclination to vote along lines similar to their peers, and conservative candidates were able to count on a strong showing among Germans living outside urban areas. Leaders, including Hitler, began using rhetoric that leaned on a rural myth, one of imagined authenticity over what Hett describes as the supposed “moral decay” of progressive cities. These myths of rural identity were then easily manipulated, much like the notion of “real America” that the GOP invokes in the face of threats from coastal elites.

Where these three books intersect most strikingly is in identifying misinformation as a precursor for authoritarianism. In The Road to Unfreedom, Snyder closely examines the ways that Putin and his government have become expert at spreading falsehoods, not by creating passable lies but by challenging the very nature of reality itself. By creating a sense that everyone lies all the time, Snyder claims, Putin is able to lie without ever needing to prove himself. All facts become suspect, so all falsehoods become possible. Hett notes that, in Germany in the 1930s, a “hostility to reality” paved the way for “contempt for politics,” which was then manipulated into disdain for the very things required for democracy to function: deal-making, favors, and compromise among the leaders of various political factions. Levitsky and Ziblatt’s warning signs of authoritarianism include a firm willingness to dismiss reality.

Is there a way forward to be found in any of these works, or in the larger body of scholarship on fascism and authoritarianism since the mid-20th century? Applying history’s lessons to unfolding events can sometimes feel like trying to grab mercury, but if these books provide anything in the way of a moral, it is that democracies do not die overnight; they die over the course of generations, as norms are eroded and leaders normalize the worst impulses in a society. These three books suggest that Trump is the culmination of many trends: white supremacy, the politics of eternity introduced by the far right, the dissolution of political norms by the GOP.

Democracy is fragile by its nature. It relies on norms, unwritten rules, and promises of a better future in order to function. As we’ve seen with the normalization of extremist views in recent years, maintaining a democracy can be messy, and sometimes the system is ill-equipped to deal with signal-jamming, particularly when leaders from across the political spectrum do not address nascent threats to democracy head-on. That is when authoritarian leaders can, and do, step in.