Nota del Editor: Para leer la versión original en inglés de esta historia, haga clic aquí.

Before the handful of Chinese guys came ashore one morning in 2014 with their GPS devices and their tape measures and topo maps and their almost comically well-armed military escorts, life in the tiny indigenous coastal village of Bangkukuk Taik, on the knife-edge of southeastern Nicaragua, was pretty much as you might expect in a place so far off the road that, well, there is no road. Or running water. Or electrical grid. Or phone service. Or Internet. Or medical clinic. Or currency. A place so insulated that few of the 150 souls here speak fluent Spanish, the national language. So isolated that the only way in or out is over the open ocean.

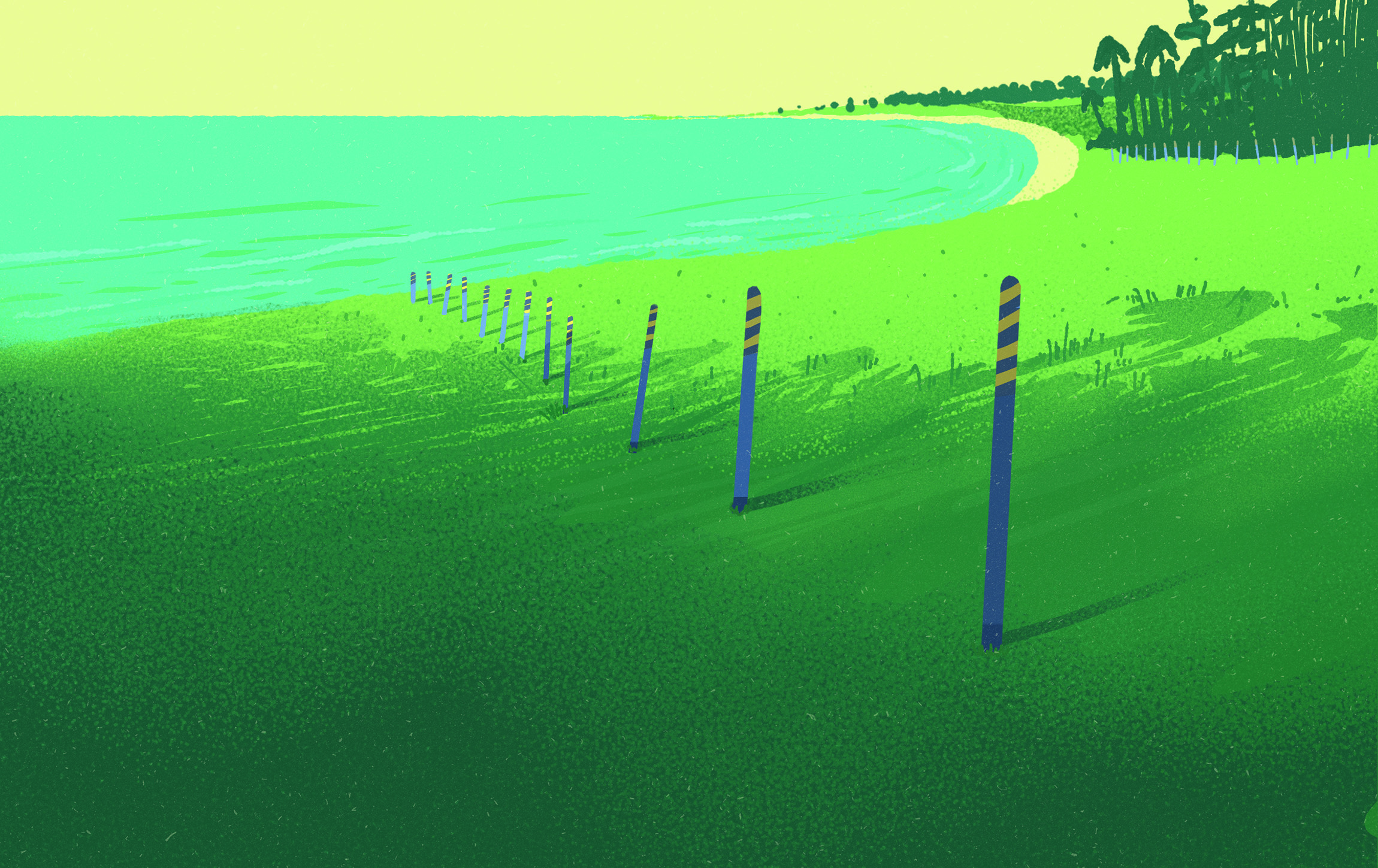

Pressed between lush jungle and wetlands on three sides, and perched on a rise above the Caribbean Sea on the fourth, Bangkukuk Taik (BAHNG-koo-kook tie-EEK) lies in the largely unpopulated lower half of the lower half of the vast swath of eastern Nicaragua that is constitutionally recognized as autonomous—territory, that is, that legally belongs to the resident indigenous populations, including the Rama Indians, the smallest and poorest indigenous tribe in a country that itself is the poorest in Central America and the second poorest in all the Americas, after Haiti. There is no industry in Bangkukuk, no wage work of any kind. The people grow their own food, keep cows and guinea fowl and pigs, and they fish with nets or harpoons from the shore or from dories—traditional wooden boats. They rely on plants and herbal remedies to cure infections and other maladies. Their water comes from wells and rain barrels. To buy clothes and other necessities they sell fish on the street in the city of Bluefields, a two-hour, spine-rattling ride up the coast by skiff. As such, Bangkukuk is generally ignored by the central government in Managua, unless some foreign investor comes knocking with a deep pocket and an eye toward its abundant natural resources.

Here Belongs to Us, by William M. Adler. Listen to more Pacific Standard stories, read out loud.

When they first landed, the Chinese visitors were deceptive about their intent; a translator volunteered only that they were “measuring the tide,” says Ronald McCrea, a Bangkukuk native. Shortly before they left, however, the Chinese planted a couple of boundary stones on a grassy bluff above either end of the crescent beach. No one here knew what the markers signified—beyond certain change. Donald H. Byers, a historian from Bluefields who has led archaeological studies in Bangkukuk, recalls that, on the day he saw the surveyors’ plaques, he told Carlos Wilson Bilis, president of the communal council: “Get ready, man. You are leaving from here.”

The Rama’s ancestors were here a thousand years before Christopher Columbus. In the 500 years since he wandered the Caribbean coast, these indigenous people have suffered Spanish conquerors and British colonizers, Dutch and French pirates, Moravian missionaries from Germany, United States banana barons and Marines. They have endured hurricanes and droughts, earthquakes and civil wars. They have survived all manner of regimes, foreign and domestic: a British governor, an American filibuster, anti-imperialist reformers, a dictatorial dynasty. The Rama withstood all those rulers, and many more, but they may not outlast the current one: President Daniel Ortega, the 1980s revolutionary icon turned 21st-century autocrat.

Ortega views the Rama and their poor-but-paradisiacal village as an affront to his swashbuckling fever dream: building a $50 billion interoceanic shipping canal that would stretch across Nicaragua for 173 miles—a distance more than three times that of the Panama Canal. The waterway would constitute the “largest civil engineering project in history,” says its prospective builder, a Hong Kong-based company. And indeed, in size, scope, and hubris, the megaproject is almost inconceivable, if not downright biblical. As Ortega put it: “For the people who have sacrificed so much, who have suffered so much pain, our people who have spent so much time wandering in the desert in search of the promised land, the day has arrived. The hour has arrived for us to reach the promised land.”

The comandante didn’t say so, but reaching that land of milk and honey—of double-digit economic growth, tens of thousands of construction jobs, hundreds of thousands of permanent jobs, and a path out of extreme poverty for more than 350,000 people—will require more pain, further sacrifice: mass expropriation of lands, the removal of tens of thousands from their homes, entire communities razed or flooded. Plans call for the 5.4-square-mile deepwater port, the spot where the canal will open to the Caribbean Sea, to cut straight through what is currently Bangkukuk Taik. According to the project’s Environmental and Social Impact Assessment, the port will require the “resettlement of the Bangkukuk Taik (Punta Aguila) indigenous village, the last Rama village where the native language is spoken.”

The tacit admission—that when Bangkukuk vanishes, so, too, will the mother tongue of the Rama—prompts larger questions, and some moral ones, about this most mega of megaprojects. What happens when the authoritarian leader of a small, poor country unilaterally hitches its economic and environmental fate (and, not incidentally, his legacy) to the whims and demands of the global economy? At what cost to national identity and sovereignty, to civic life, participatory democracy, the natural world?

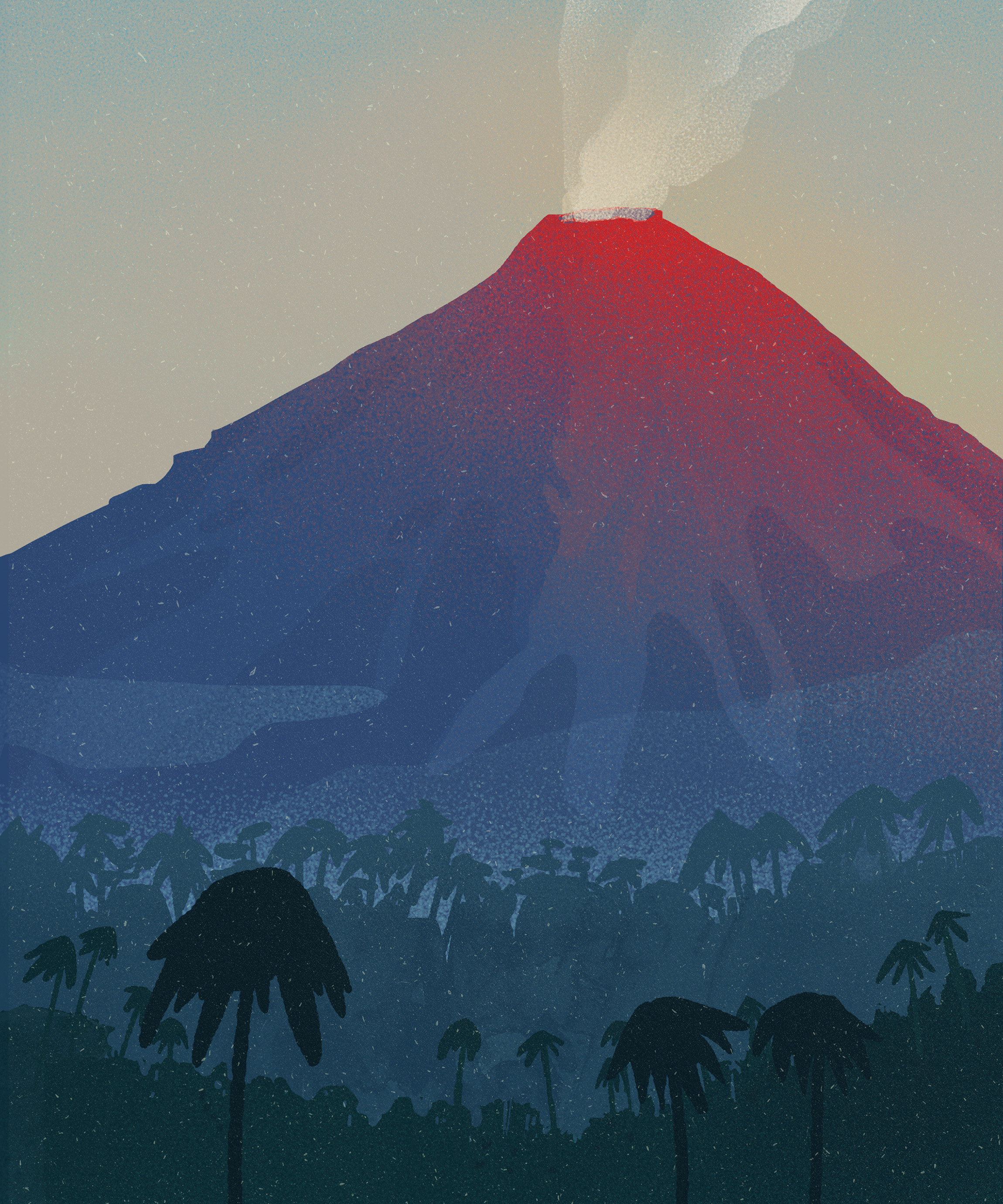

Everywhere along the 173 miles there will be winners and losers. From the Caribbean coast inland through the wetlands and natural reserves of indigenous lands, to the farm communities along the eastern shore of Lake Nicaragua, and on across the great lake for 65 miles, passing just south of Ometepe, the lush, hourglass-shaped island with twin volcanoes that a bedazzled Mark Twain once described as “clad in the softest and richest green,” and on to the fishing and farming hamlets of the lake’s western shore and beyond, straight through to the Pacific coast.

Surely no community has more to lose than the ancient, already marginalized people of Bangkukuk. Not only would their language likely disappear, but so would the whole of their profoundly intertwined culture, the only world they’ve ever known: their communal land, their homes, their daily work of farming, fishing, planting, hunting, gathering, their sacred sites and customs and traditions, their very sense of self. Where would they go? And should the sacrifice demanded of one invisible, indigenous village diminish the greater good and glory that an interoceanic canal, this reoccurring centuries-old dream, would theoretically bring Nicaragua?

One late summer Sunday morning, I was going door to door in Bangkukuk with the grandly named Randolph Evans Beacon Cunningham, a gregarious fellow who agreed to be my guide and translator. (Although their native language is Rama, most villagers speak “Rama English,” a version of Creole English as impenetrable to me as the surrounding jungle.) People were reserved but friendly enough, greeting us as they tended their gardens and their children, or cooked, or cleaned house, or lounged in hammocks.

The village consists of some 45 scattered houses, a two-story communal building, a whitewashed Moravian church, and a tumbledown, one-room school for first through fifth grade. The houses are simple, nailed-together wooden structures: one to three rooms, some with an indoor kitchen. About half the homes now have solar panels, courtesy of a Bluefields-based non-governmental organization (NGO). None have plumbing. Though there are two communal latrines and three private ones, most residents choose the great outdoors. (I did too. “Use leaves,” Randolph instructed as I disappeared behind a banana tree. “We double it.”) Most houses are on stilts, the better to mitigate the mud or dust, depending on the season. The homes are sparsely furnished: a bed or two, and some hammocks strung between posts. Big windows catch the breeze, some fitted with hinged shutters, none with glass or screens. The roofs are fashioned from royal palm straw or sheets of zinc-plated steel scavenged from Bluefields. Some yards are fenced with chicken wire to keep livestock in or out. No yard has a gate, which means scooting under the lowest wire to come or go.

On this morning, Cheryl Dont, a 61-year-old lifelong resident of Bangkukuk, wore a threadbare, sleeveless, blue housedress that reached almost to her bare feet and the dirt floor of her one-room, thatched-roof cabin. (Hers was one of the few homes not on stilts.) One of her 11 children, Evelyn, had stopped by for breakfast with her five-year-old son. Evelyn, who was 25, told me the scuttlebutt that the government planned to relocate everyone to Bluefields.

Bluefields is the capital of the South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region, as this quarter of the country is known, and is named for a Dutch pirate who admired the harbor for its remoteness, even by the standards of the 1600s. Today, it is a gritty, dense city of about 60,000, awash in equal parts charm and squalor, and with more than a hint of both police- and narco-menace (owing to its strategic locale as a far-flung Caribbean way station for cocaine en route from South America to the eastern U.S.). Like everyone born and raised in Bangkukuk, for Evelyn and Cheryl, moving to Bluefields seems inconceivable.

Everywhere in Bangkukuk, I heard the same deep-seated fear: that the canal would mean relocation and ruination. “If they put it through, we can’t find the food to eat; we can’t find fish; we can’t find nothing,” said Lucila Hodgson, an elder who was raising her grandson, who has developmental disabilities. I asked where she would go if she had to leave. “I can’t go nowhere, you see, because we need the bush for plant, and if you can’t plant you can’t get nothing for eat. If you no plant, you are dead.”

“What about Bluefields?” I asked. “Could you make it there?”

“In the town, you don’t have money, you not eat. But here in the bush you plant, you raise your animals, catch a fish, get a coconut—you can eat.”

On the front porch of his house, David Wilson was even more worried, but also defiant. He said that the government and the canal company have no right to build on autonomous Rama land—not without consent of the Bangkukuk communal board. His family’s laundry swayed in the breeze from the rafters above, and his three young children flitted around us like hummingbirds, but David was as forceful as a prosecutor, as righteous as a preacher. “We Rama people,” he said. “We native from here. We don’t come from nowhere else. We born here, we live here, we grow here, we die here, and we always here. So if the government wants to put the canal, it should look at a place that belongs to the government, right? Because here not belongs to the government. Here belongs to us.”

The government ought to understand Wilson’s simple argument. It is, after all, enshrined in the Nicaraguan constitution—drafted and ratified in 1987, during Ortega’s first term in office. By that foundational law, the state promises to recognize communal land ownership of the communities of the Atlantic coast; it pledges to preserve and develop these communities’ cultures, languages, religions, and customs; and it affirms that these communities should benefit from and enjoy the waters and forests of their communal lands.

In more recent years, the government passed Law 445, demarcating the 23 indigenous territories of the Atlantic coast as autonomous regions, and signed on to both the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the International Labour Organization’s Convention 169, which requires signatories to obtain “free and informed consent” prior to removing indigenous people from their traditional lands.

But in Ortega’s Nicaragua, the Reverend Cleveland McCrea, a Rama pastor, once told me, “autonomy is just words on paper.”

Three centuries before there was a Republic of Nicaragua, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés foresaw the geostrategic advantages of a shipping route across the Central American isthmus. “He who controls the passage between both oceans may consider himself the master of the world,” Cortés wrote to his patron, King Charles V, in 1524. Pretty much continuously ever since, a revolving cast of European emperors and kings, admirals, pirates, robber barons, diplomats, adventurers, American presidents, and Nicaragua’s own ruling elites have been tantalized and tormented by the prospect of linking the oceans through Nicaragua. Engineers and cartographers drew dozens of plans for a waterway across the southern portion of the country.

Napoléon III gave it a shot in the 1840s, but the press of events in France ultimately distracted him. Cornelius Vanderbilt, the 19th-century U.S. railroad tycoon, went a step further: He broke ground, if barely. Aiming to cash in on the Gold Rush traffic between the east and west coasts of America, he dug a little over a mile inland from the Caribbean side.

Finally, at the turn of the 20th century, it looked as if a U.S.-backed canal would be built. It came down to a congressional debate as to whether to finance a big dig through Nicaragua or the Panamanian isthmus. Nicaragua was the early favorite—its route was roughly 500 miles closer to the U.S. border than Panama’s, and its topography more promising—but that was before the great postage-stamp ploy. As the U.S. Senate neared the deciding vote in 1901, Panama’s principal lobbyist mailed a Nicaraguan stamp to all 90 senators. The stamp portrayed the Momotombo volcano “in magnificent eruption”—a sure sign, it was said, of the dangers of constructing and operating a canal in such a seismically volatile zone. The Panama Canal opened in 1914.

But even that monumental achievement could not dull the appetite of Nicaraguans for a canal of their own. Take Augusto César Sandino, the fabled guerilla warrior who led the resistance to U.S. military and corporate incursions in Nicaragua during the early 20th century. Sandino saw a canal—a Nicaragua-owned and -operated canal—as the means of ensuring national sovereignty and self-determination. But the country’s national guard assassinated Sandino in 1934, and the dream of the canal seemed to pass with him.

Yet like Sandino himself, who was resurrected as namesake and ubiquitous symbol of the 1979 revolution that overthrew the dictatorial Somoza regime and begat Ortega, the canal dream never really died. But it was always a mirage on the near horizon, never within reach—until now. The current incarnation dates to the first term of Ortega’s second coming as president. In 2007, he invited five nations—China, Japan, Venezuela, Russia, and South Korea—to join Nicaragua in a canal-making consortium. He hired a Dutch firm to produce a pre-feasibility study, and in July of 2012, prodded the national assembly to pass Law 800, which created the Nicaragua Canal Authority and outlined the project’s legal framework. The law called for a public-private partnership, with Nicaragua as a 51 percent shareholder. It directed compliance with national and international standards for environmental protection, and mandated, per legal precedent, a “prior free consultation” with people living in indigenous territories. Law 800 was hardly perfect, but in its acknowledgment of certain environmental and social dimensions of the megaproject, in its deference to constitutional law and national sovereignty, it sounded downright harmonious next to a tone-deaf law that Ortega would ram through a year later.

By then, Ortega had abandoned the public-private consortium model in favor of a fully privatized concession agreement—and abandoned, too, the principles and ideals of the revolutionary movement that propelled him to the presidency. He remains the titular head of the Sandinista National Liberation Front, but now 72 and in his third consecutive five-year term as president, his rebel days are far behind him. With his wife Rosario Murillo, the current vice president, positioned to succeed him in 2022 (and with their adult children waiting in the wings), Ortega’s legion of critics say the Ortegas are a new political dynasty of the old order: corrupt, wealthy, authoritarian. “Their public discourse is left-populist,” says Luisa Molina, a former inner-circle Sandinista who now heads a human-rights NGO in Managua, “but in practice they use repression, the army, the police, paramilitary groups” to maintain control.

During my time in Nicaragua, I heard many of his former comrades mention Ortega in the same breath with Somoza. “We’re Sandinistas,” they like to say, “not Danielistas.”

Good morning, good morning. Yes, yes, once more, good morning to each and every one of you. … Well, right now in the radio studio, we have 9 o’clock with 36 minutes. … And at this time, I would just like to say, good morning, good morning, Miss Dolene. So, what say, girl?

Nora Newball and Dolene Miller were squeezed inside the studio of Radio Siempre Joven (“Forever Young”), 99.1 on the FM dial. The no-frills station shared one wall with a restaurant kitchen inside a peeling downtown Bluefields hotel. Another wall was pocked with derelict egg crates that once, maybe—maybe—served as soundproofing. Dolene was 53, Nora 51. They are lifelong community activists who have been producing their public-affairs show for a dozen years, long enough that they’re the sort of friends, on air and off, who finish one another’s sentences. They sat elbow to elbow at a round table laden with their tools: notepads, a pocket-sized Nicaraguan constitution, news clippings, highlighted copies of national and international statutes. It was the morning after hundreds took to the streets of Bluefields to demonstrate against the canal. It marked the 50th such march nationally and the first in the South Caribbean Coast Autonomous Region. Dolene and Nora helped organize the march, spoke at it, and got in the face of police who tried to stop it. (Nora produced for them the municipal parade permit she safe-kept in her bra.)

Nearly every Saturday for over a decade now, Dolene and Nora have taken to the radio to school costeños, or coastal dwellers, about their special legal rights as citizens of the autonomous region of Nicaragua. Both are Afro-descended Creole; their families have been in Bluefields for more than a century. And sometimes it seems like they’ve been waiting nearly that long for the central government in Managua to comply with the 2002 autonomy law, which requires that it demarcate and title the territorial land of the Creole people of Bluefields. Thus the name of their weekly show: “Demarcation Now.”

No. 1 topic we have to share with you this morning: Why the march? Why we march? And in that context, woof, there’s just a whole lotta things! This morning we plan to educate you, to teach you about the canal law.

And so they did. Over the course of the next hour or so—minus a 27-minute power outage at the station, which invariably occurs, they say, when the Sandinista-controlled electric utility disapproves of the discussion topic—Nora and Dolene offered a master class in the art of radio as a tool for citizen organizing and popular education. They talked to their listeners, not at them; they took calls, encouraged people to do their own research. “When we started the radio show in 2005,” Nora told me during a musical break, “some of them was saying this is too difficult; you all are crazy; this will never happen; be very careful. But we insisted we have a law, and we have instruments to protect our land. And we started creating consciousness on the radio.”

We know there is a lack of information toward this canal law. And you know it has been such a delicate topic, because here in Bluefields is … just like Managua, right? These two places are political centers … and they’re going out and making all this huge propaganda about all the benefits that the canal would bring. … So with the march … it gives us an opportunity to share with you, so that you could understand more about the negative part of this canal law. So we will be talking about that. And about the organization of this Law 840—the canal law—and the historical part of it. Because this law wasn’t just born yesterday.

The birth of Law 840 could almost be said to be accidental. Shortly after Law 800 passed, in 2012, President Ortega’s son, Laureano, was in China on a trade mission to enlist a telecom vendor for a national wireless network for Nicaragua. While in meetings with Chinese government and business leaders, the subject of the nascent canal proposal arose. Laureano knew few of the details, but he knew to call Manuel Coronel Kautz, the octogenarian president of Nicaragua’s newly formed canal authority. Coronel Kautz emailed him a copy of the pre-feasibility study and deputized him to “officially” represent Nicaragua. But the governments of China and Nicaragua did not formally recognize one another, so the Chinese official told Laureano to seek out “private enterprisers.”

The first enterpriser Laureano met with was Wang Jing, the then-39-year-old chairman of Beijing Xinwei Technology Group. Xinwei was a struggling commercial firm when Wang assumed control in 2009. He redirected the company’s resources “into the military, into defense,” Peter Liu, a Chinese venture capitalist and former shareholder in the company, told the online publication Diálogo Chino. Wang’s military strategy proved a boon for the publicly traded Xinwei and for his own fortunes. In June of 2015, before the Chinese stock market tanked that fall, the value of his 35 percent stake was estimated to exceed $10 billion.

Wang promptly reviewed the canal proposal. “I love this,” he told Laureano, according to Coronel Kautz. “I’ll do this with you!” A month later, Wang’s private jet landed at Sandino International Airport in Managua. Over the next few months of meetings, Wang came to insist on a concession rather than a joint venture. The canal authority embraced Wang’s proposal once he offered to assume all the risks and pay for all the costs.

Wang is often, and justifiably, described as enigmatic. He gives few interviews (his public relations people ignored multiple requests) and reveals little of himself to those reporters he does speak to. In 2014, he divulged to a Reuters correspondent that he was born in Beijing in December of 1972, that he studied traditional Chinese medicine before moving to Hong Kong to learn about international finance, and that he tried mining gold and precious stones in Cambodia. On another occasion, he allowed that he lives with his mother, brother, and a daughter. “I’m a very ordinary Chinese citizen,” he added. “I’m so ordinary that I couldn’t be more ordinary.”

However modest Wang’s background, his qualifications for financing, building, and managing the self-described “largest civil engineering project in history” are exponentially more limited. His lack of professional credentials might have been an impediment to his bid for the canal concession if the government of Nicaragua had invited competitive bids, but it did not. Nor did it hold public hearings on the canal-concession bill, or permit substantial legislative debate, or assess the project’s feasibility, or environmental and social impact. Instead, Ortega cut a secret deal with Wang seven months before the legislature formally considered the concession.

The document—dated October 31st, 2012, and marked “Strictly Private and Confidential”—granted Wang’s newly incorporated firm, HK Nicaragua Canal Development Investment Co., Ltd., or HKND, the right “to undertake the construction, operation and administration” of the canal. More than that, the agreement was as breathtakingly generous to HKND as it was oblivious to the constitution of Nicaragua. Perhaps this can be attributed, says Coronel Kautz, to the previously unreported fact that HKND itself—or rather a pair of attorneys from the Chicago-based law firm it retained, Kirkland & Ellis—wrote the bill. Maybe, too, the generous terms can be attributed to the fact that most members of the national assembly had no idea what they were about to vote on: HKND’s lawyers wrote the 44-page bill, plus the 120-page master concession agreement, not in Spanish, but in English—the language in which La Gaceta, Nicaragua’s version of the congressional record, first published it.

All those pages of English amount to an exclusive no-bid concession that grants HKND a 50-year contract (with a second 50-year option) to build and operate the canal. It also includes the option to develop a number of “sub projects“: an international airport, unspecified “holiday” resorts, roads, an oil pipeline, a free-trade zone, and the two deepwater ports in both oceans. The concession strips the State of Nicaragua of the initial and permanent majority-ownership status provided for in Law 800, instead stipulating that Nicaragua will eventually be granted 50 percent ownership, but in increments of 1 percent per year for the 50-year duration of the concession. It also guarantees Nicaragua an annual fee of $10 million for the first 10 years, with a slowly increasing percentage of the profits after that first decade.

In June of 2013, when the Ortega administration finally presented the bill to the national assembly, the Sandinista-dominated legislature debated it for all of one day before it rubber-stamped a law that not only surrendered a huge swath of the country’s territory for a century, but also granted HKND the right to select the path of the canal. A private, foreign corporation now held the unchecked power to displace up to 120,000 Nicaraguan citizens from their homes and expropriate any and all private property it deemed necessary for the canal or the sub-projects, including lands such as Bangkukuk Taik that are within ostensibly autonomous territory.

Within weeks of the law’s passage, human rights and environmental lawyers filed 31 cases on behalf of 183 plaintiffs. The Ortega-packed supreme court of Nicaragua was unfazed; it swatted away all 31 in one day. Not only that, the national assembly retrofitted the constitution to further legal-proof the concession. As Mónica López Baltodano, an anti-canal activist and environmental lawyer who brought many of the suits, wrote, Ortega’s government was “adjusting our Magna Carta to big capital’s corporate interests.”

On the morning of December 22nd, 2014, the government announced what it has previously heralded as a “Christmas present” for its six million citizens: the start of canal construction. At a nationally televised ceremonial groundbreaking in Brito, a Pacific coast fishing village near where the canal’s western terminus and deepwater port would be built, government and HKND officials donned hard hats and led presidential hosannas—“Daniel, Daniel!”—amid a backdrop of two hundred construction workers and flag-waving kids in Sandinista-loyalist T-shirts. As confetti—confetti!—rained on the crowd, Wang took the stage. “This moment will surely be inscribed in history,” he said. Wang and his entourage had traveled the 60 miles from Managua to Rivas, the city nearest Brito, by helicopter. Flying avoided confrontation with a few hundred anti-canal protesters who were blockading the Pan-American Highway.

Those angry citizens had good cause for concern. Rivas is a narrow strand bounded to the west by the Pacific Ocean and to the east by Lake Nicaragua. As the go-between from seawater to fresh, it is a wellspring of farming, fishing, and, increasingly, tourism. Its 178,000 residents rely on both sources of water for their livelihoods. So when Chinese surveyors and land assessors, accompanied, per usual, by heavily armed Nicaraguan soldiers, began showing up in the towns and villages of Rivas a few months before the groundbreaking ceremony in Brito, the locals were unwelcoming. Signs sprouted everywhere: No Canal, Chinese Out; We Will Not Sell Our Land; and Ortega Sellout.

Beyond their fears of expropriation and the certainty of prolonged turmoil posed by the coming of the canal, the gravest concerns of many in Rivas center on Lake Nicaragua. At 3,000 square miles, the lake is the largest fresh water reserve in Central America, a major source of irrigation, and the primary source of drinking water for 200,000 people. “If something affects the lake,” an environmental activist in Rivas told me, “it affects everyone around here.”

Sixty-five miles of the canal—more than a third of the entire route—would cross the lake, but the relatively shallow lakebed would need to be dredged. To accommodate the sort of gargantuan container ships that Wang is banking on to transit the canal—so-called “super-post-Panamax” ships, too large even for the recently expanded Panama Canal—the company proposes to dig a 65-mile channel up to 98 feet deep and up to 1,700 feet wide, at great risk to the ancient lake’s diverse but fragile ecosystem. And HKND proposes to dispose of all that displaced sediment—an unfathomable 1.2 billion tons—by creating three islands and simply dumping the rest in the lake, despite warnings from an independent panel of scientists that doing so could potentially create “dead zones.”

The international scientific panel, assembled by Florida International University’s Southeast Environmental Research Center and College of Law, also raised concerns about the impact of traffic and fuel spills on the lake; about the likely introduction of salinity and invasive species from the sea; about the threat to the fresh water supply; about how the canal’s water use could exacerbate the effects of drought as the climate warms. Manuel Ortega Hegg, the president of the Nicaraguan Academy of Sciences and a sociologist at the University of Central America in Managua, told me he felt betrayed by the administration of Daniel Ortega (no relation). “There’s a feeling of being upset,” he said, “but mainly a feeling of disillusionment.”

Still, a 2015 public opinion poll showed a clear majority of Nicaraguans, around 60 percent, favored the canal. Certainly its appeal is clear, at least from a distance. Nicaragua has been trapped in a centuries-long cycle of dependence and poverty. And along comes this reoccurring dream. And this time the dream is real: Look, here’s the comandante leading us to the promised land. There’s the Chinese billionaire promising that “making this dream a reality will bring more happiness, more freedom, and more joy to the world.” And over there is Vice President Rosario Murillo, the comandante‘s wife. On the day the canal was announced, she declared it a “day of miracles.”

Lord knows Nicaraguans could use a miracle. Of the country’s six million people, 30 percent survive on less than $2 a day. So it was no wonder, Ortega Hegg told me, that so many are standing in line for their tickets to the comandante‘s promised land. “I’m not surprised, because the big issue is employment. And now here comes a project that is going to magically provide 1.2 million jobs—and without any explanation of the negative impact. I’m not surprised that the majority of the population will support this project.”

Ortega Hegg and I first spoke in 2015, not long after the poll results were released, and not so long after the groundbreaking ceremony in Brito. Three years later, not another spadeful of dirt has been turned, ceremonial or otherwise. The most recent opinion poll, taken in January of 2016, indicated that Nicaraguans were no longer so smitten with the project. One-third believed the canal is “pure propaganda”; a quarter believed that additional technical studies are called for; and 13 percent thought there was insufficient money to complete the project.

Outside Nicaragua, the canal has come to be regarded as a doomed project, a victim of Wang’s personal financial convulsions, a grandiose yawn from international markets, and, perhaps most significantly, Ortega’s increasingly tenuous hold on the presidency: A non-violent civilian uprising, begun in the spring of 2018 and led in part by anticanalistas, may well knock him from power before his current term expires at the end of 2021. All that aside, shipping and trade experts have recently questioned whether the canal could ever be economically viable in the wake of Panama’s move in 2017 to break diplomatically with Taiwan in favor of China. That agreement suggests that the Chinese government, once considered Wang’s puppeteer in Nicaragua, is content to route its insatiable appetite for trade with the Americas through Wang’s would-be rival for transoceanic shipping, the Panama Canal.

Inside Nicaragua, protesters led by the grassroots National Council in Defense of the Land, Lake, and Sovereignty, remain on the march, pressing for repeal of Law 840. They’ve held nearly a hundred anti-canal demonstrations, many in the face of government menace and repression. How long will they keep marching? The council’s current leader vowed, “For 50 years if we have to—or a hundred.”

This story was produced in partnership with the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.