Last week, the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps program, a collaboration between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, released its annual rankings. The rankings examine both standard health outcomes and the various factors that influence people’s health—unemployment, access to healthy foods, high school graduation rates, air and water quality, and so forth. This year’s rankings confirm a finding that’s been showing up in a lot of research over the past year: America’s rural counties aren’t doing so well.

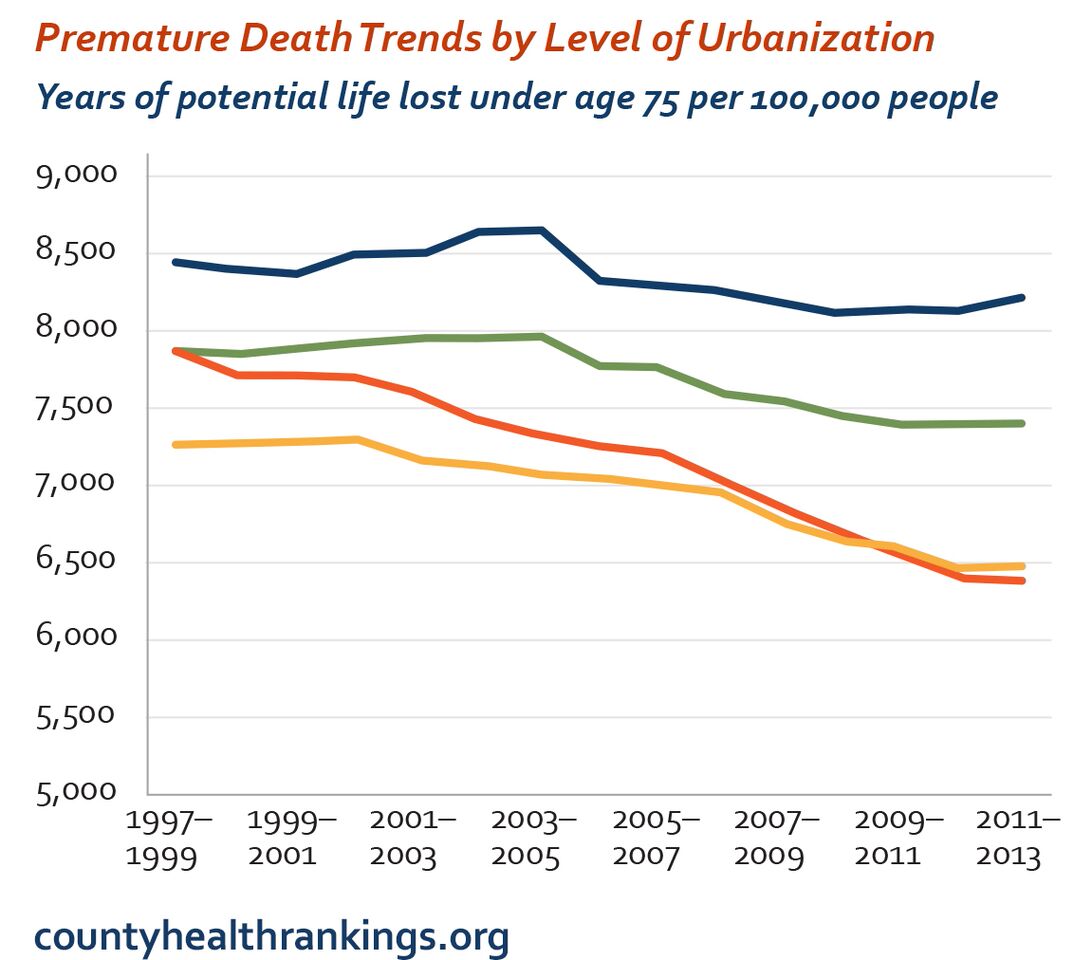

“Rural counties have had the highest rates of premature death for many years, lagging far behind other counties,” the accompanying report concludes. “While urban counties continue to show improvement, premature death rates are worsening in rural counties.”

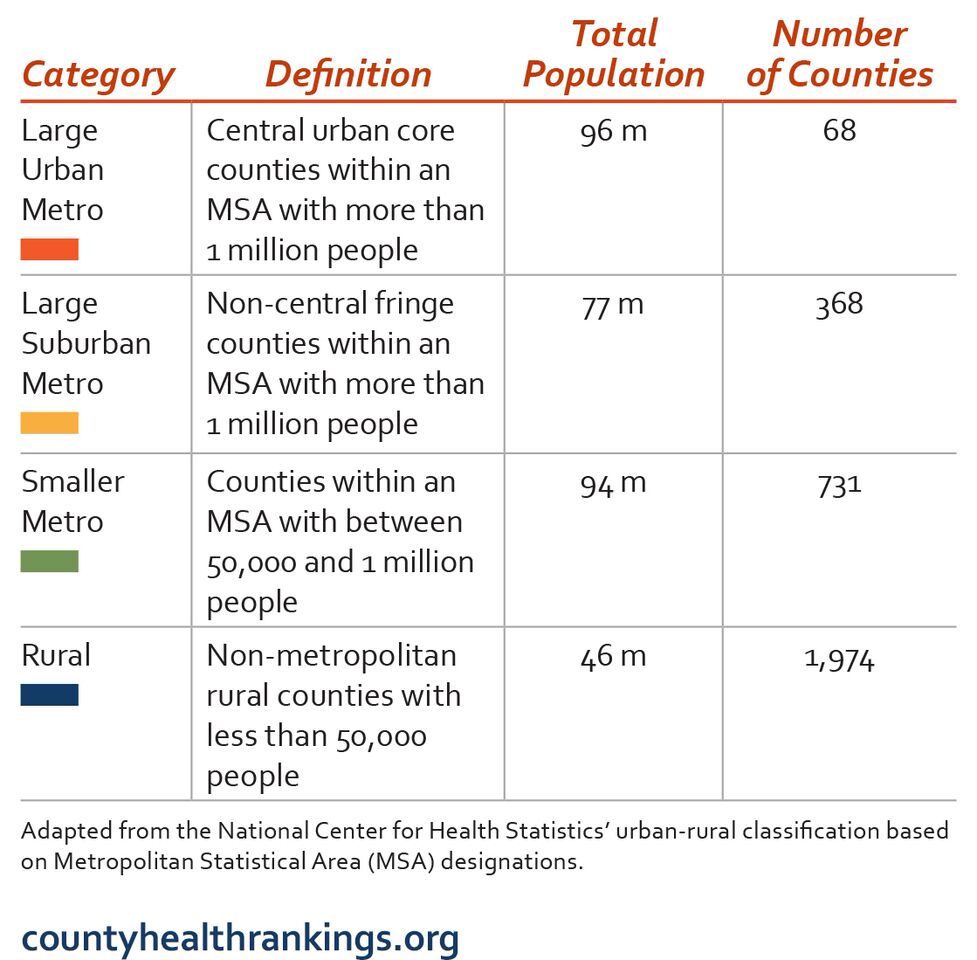

The graph below (and accompanying key), which charts “years of potential life lost,” illustrates the recent increase in premature death rates in rural counties.

There are a number of factors driving the trend: Rural counties score worse on measures of smoking, obesity, and poverty, and they have also been disproportionately affected by the opioid crisis and epidemic of drug-related deaths (accidental or otherwise) that has swept the country in recent months. But perhaps even more damning than demographics or addiction, these areas are plagued by a shortage of medical professionals: There are simply not enough doctors in rural counties.

Rural counties aren’t the only places facing physician shortages. The Health Resources and Service Administration is predicting a shortage of over 20,000 primary care physicians by the year 2020, thanks to both population growth and demographic trends (i.e., the aging of the Baby Boomer generation). Last year, the Kaiser Family Foundation proposed an interesting potential solution to the primary care physician shortage, one that deserves further attention during this health-care–obsessed election cycle: nurse practitioners.

Nurse practitioners are advanced-practice registered nurses (APRNs) who have undergone additional education (a master’s degree, at least) and training, and are qualified to independently manage and provide care. There are limits to the sort of care nurse practitioners can provide—they can’t perform surgery, for example, and aren’t trained to manage certain kinds of complex conditions—but, according to the Kaiser report, nurse practitioners could manage “80-90% of care provided by primary care physicians.” Nurse practitioners require fewer years of training and are already substantially more likely to provide care to vulnerable, underserved, and uninsured patients.

A sizable body of evidence suggests that APRNs provide the same quality of care (and often at lower prices) as physicians. A 2005 article from the Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews that reviewed 16 studies on nurse-provided primary care found similar health incomes for patients cared for by nurses and doctors. Furthermore, patients who received their primary care from doctors reported higher levels of patient satisfaction; the authors reported that “[n]urses tended to provide longer consultations, give more information to patients and recall patients more frequently than did doctors.”

So what’s the hold-up? In 31 states, nurses are limited by scope-of-practice laws which require them to practice in collaboration with, or under the supervision of, a physician. The laws have become a controversial issue—doctors lobby for restrictive scope-of-practice laws on patient safety grounds, while nurses (and most economists) claim that doctors are engaging in protectionist, anti-competitive turf guarding. In 2011, for example, the Institute of Medicine released a report on the future of nursing—one of its key recommendations was to “remove scope of practice barriers.” An American Medical Association board member promptly released a statement opposing the suggestion, arguing that “[a] physician-led team approach to care—with each member of the team playing the role they are educated and trained to play—helps ensure patients get high-quality care and value for their healthcare spending.”

But in the face of projected shortages and the government’s growing role in health care, groups like the American Medical Association may be fighting a losing battle. President Barack Obama’s administration has waded tentatively into the debate—the Affordable Care Act included up to $50 million of funding for nurse-managed health clinics, as well as other efforts to support and train APRNs. And in 2014, the Federal Trade Commission issued a policy paper and statement advising policymakers to tread cautiously with respect to scope-of-practice laws:

Numerous expert health care policy organizations have concluded that expanded APRN scope of practice should be a key component of our nation’s strategy to deliver effective health care efficiently and, in particular, to fill gaps in primary care access. Based on our extensive knowledge of health care markets, economic principles, and competition theory, the FTC staff reach the same conclusion: expanded APRN scope of practice is good for competition and American consumers.

America’s health-care system continues to be plagued by substantial inequities, and it’s clear that nurse practitioners and other APRNs can play a crucial role in correcting those pitfalls—and perhaps introducing some cost savings while they’re at it.