Artist Olafur Eliasson’s “Little Sun” started out as a kind of social sculpture. Eliasson, who is known for making perception-altering installations like an artificial sun in London’s Tate Turbine Hall museum, created a tiny lamp shaped like a flower with a solar panel on one side and a light on the other. The project makes solar energy useful on a small scale, “addressing the need for light in a sustainable way that benefits communities without electricity,” its website explains.

Available for $30, the Little Sun is both more than an art project and more than a business. Eliasson donates the lamps to local entrepreneurs in areas of Africa without electricity, making them solar-energy evangelists as well as small business owners. Recently, Bloomberg Philanthropies invested $5 million in Little Sun, the foundation’s first-ever “impact investment”—an investment made with both social good and profit in mind.

By eliminating users’ need for toxic kerosene-burning alternatives, “solar-powered lights can improve their health—and at the same time, protect our environment—by keeping pollutants out of the air they breathe,” Michael Bloomberg said in the investment’s press release. Eliasson’s project also comes with a Bloomberg-approved business plan, something solar power has been lacking over the past few decades.

Little Sun is a good example of how the market and environmentalism don’t have to compete: Both the company and its evangelists are motivated to propagate an affordable form of non-polluting energy. The economics are working in concert with solar’s advantages of sustainability and independence over traditional power sources. And, suddenly, that intersection of efficacy and impact is making solar power as a whole more desirable than it’s ever been before.

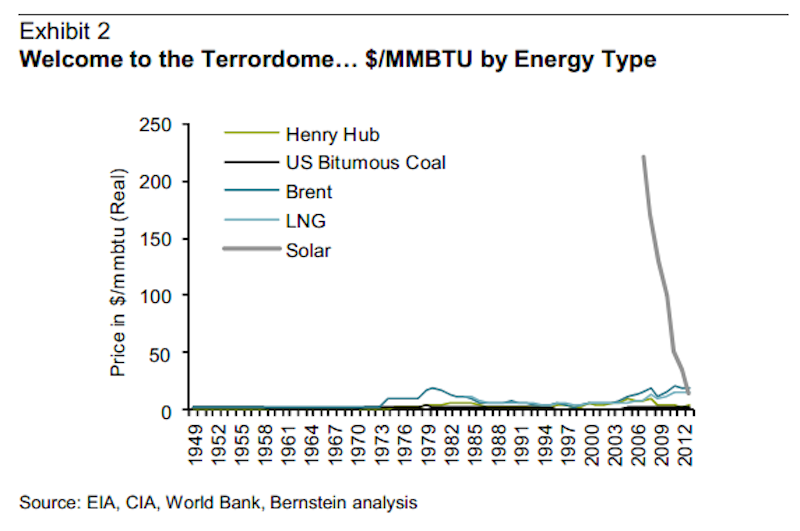

The investment management company AllianceBernstein recently released a report on the comparative costs of various forms of power, and the results are staggering. Check out this chart.

(Chart: AllianceBernstein)

The prices of crude oil, coal, and liquefied natural gas per unit of energy are represented by relatively straight lines along the bottom of the graph. Sure, there are bumps and variations, but for the most part the costs of these forms of power have held relatively steady over the past 60-plus years. Solar, on the other hand, is represented by the line that’s falling like a meteor over the past several years, even dipping below the other lines. The graph shows that it’s now possible for solar to cost less than even natural gas or oil.

While solar’s renewability and low environmental impact are great arguments for its use, the ultimate condition that will drive adoption on a massive scale is market efficiency. And we’re reaching that point. That precipitous chart is what “the solar industry has been working towards for 60 years,” write Michael Parker and Flora Chang, the authors of the AllianceBernstein report.

“Solar is now—in the right conditions—cheaper than oil and Asian LNG [liquefied natural gas] on an MMBTU [million British thermal unit, the standard form of energy measurement] basis,” Parker and Chang write. That doesn’t mean that it will suddenly be cheaper to buy a few solar panels and power your home—the price parity currently holds only in certain areas—but it is an important point on the path to widespread solar adoption.

“For these markets solar is just cheap, clean, convenient, reliable energy. There is a massive global market for cheap energy and that market is oblivious to policy changes.”

The graph doesn’t refer specifically to domestic solar energy or solar panel prices. Rather, it’s “utility scale” solar, solar-derived electricity that is produced on a large scale and fed into the power grid, then sold. “We are using utility-scale solar costs in developing markets with lots of sun,” the report explains. “But that describes the growth markets for global energy today.”

In other words, market demand is finally dovetailing with sustainability. But it’s not really for sustainability’s sake. “For these markets solar is just cheap, clean, convenient, reliable energy,” Parker and Chang write. “There is a massive global market for cheap energy and that market is oblivious to [environmental] policy changes.” And solar, with its constant supply, is getting even cheaper, unlike other forms of energy. Since traditional energy sources are scarce and getting scarcer, “fossil fuel extraction costs will keep rising,” according to the report. “Since [solar] is a technology, it will get even cheaper over time.” So that steep line will keep falling.

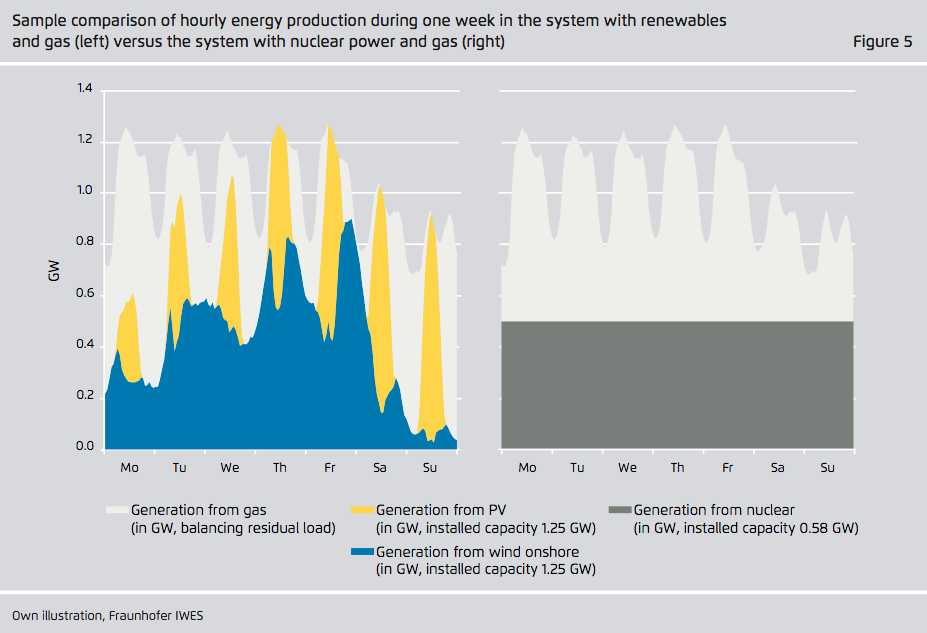

It’s not just oil and coal that solar is gradually beating. Renewable energy sources are also getting cheaper than nuclear power, according to a new report from Germany’s Agora Energiewende, a group focused on clean-energy transition (which their name translates to in German). “New wind and solar power systems can generate electricity up to 50 percent cheaper than new nuclear power plants,” Patrick Graichen, Agora Energiewende’s executive director, said in the report. “A reliable power system based on wind, solar, and natural-gas power plants would be 20 percent cheaper than a power system based on nuclear,” the report concludes.

Solar and wind power have a few major advantages over nuclear energy. They don’t require any added input to keep drawing energy from the wind or sun. As Agora’s report shows, the construction of renewable energy plants results in cheaper power in the long run since upkeep costs are lower. Solar and wind also produce power over the same time period it is needed; the plants naturally create more electricity when demand is high during the day (the sun comes out during the day, of course, and wind is more active when the air is heated).

(Chart: Fraunhofer IWES)

In January of this year, Eric Lipman, the administrative law judge for Minnesota’s Public Utilities Commission, had to choose what form of energy he would invest in with state funding. Lipman chose solar—not for its environmental friendliness, but for the fact that it was cheaper and able to function on a smaller, more local scale. “It seemed that nonrenewable energy sources always won the head-to-head cost comparisons,” Lipman said in his announcement. “Not anymore.”

To reverse the old adage, power is money, and it looks like solar and other renewable energy sources are finally becoming financially desirable to the point that they will begin to displace our earlier, more noxious options. Whether it’s Eliasson’s Little Sun or the world’s largest solar plant, which opened in California in February, that’s a great thing for us as well as the planet.