When Philadelphia’s subways still closed around midnight on the weekends, the last train was usually a raucous one. Those who managed to tear themselves away from the bars and dance halls two hours before closing had still been out long enough to thoroughly indulge in their intoxicant of choice. Party-goers bounced around the day’s final subway cars, singing, chatting, laughing.

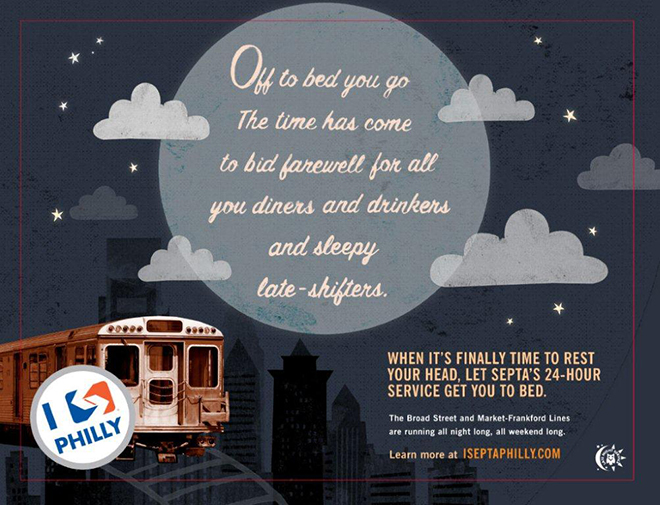

This past June the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) announced a summer-long experiment with 24-hour weekend service. There was much rejoicing, especially among the set who prefer to stay out until the proprietors shut the lights off. SEPTA isn’t known for its promotional acumen—their old slogan, “We’re Getting There,” is easily interpreted as a resigned shrug—but it released a series of surprisingly charming posters to advertise the new hours: “Goodnight Theater, Goodnight Stars, Goodnight Nightclubs, and Cafes and Bars,” one reads.

The marketing campaign was “targeted toward the 21-to-34 millennial crowd who would be interested in the service in general,” says Manuel McDonnell Smith, public information manager for SEPTA. “There’s really been a transformation in [these last] 15 or 20 years, more night life and things to do in the evenings.”

“When I worked in the Old Navy in The Gallery, they had us do monthly inventory until 2 or 3 in the morning. It was not fun. But you know what was even less fun? Waiting on the corner of 8th and Market for 40 minutes for a bus that would end up being packed.”

The late-night trains are very useful for getting back home without an expensive cab ride or an ill-advised (and illegal) drunk biking expedition. But the post-midnight trains mostly aren’t dominated by party-goers, excepting perhaps those immediately after 2:00 a.m. closing time. The ridership is, if anything, more sedate than during normal hours. Heads nod, quiet reigns: Many of the occupants seem to be returning home from work. On a recent evening, around 1:30 in the morning, the occupants of a west-bound train on the Market-Frankford line were mostly African-American and mostly, it appeared, dead tired. But when roused from ear-bud-enabled reveries, they enthused about the service.

“I think it’s a great idea, it’s too bad it doesn’t run late every night,” says Paul, a middle-aged African-American man. “I’ve never had any problems, never had any bad experiences. I’m a utility worker at a restaurant, so I get off late. I just wish it ran more times an hour.” (The service runs every 20 minutes, as opposed to four to five times an hour during the daytime.)

A poster advertising new public transportation hours. (Photo: SEPTA)

Until 1991 Philadelphia’s subways operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week, due to economic necessity: Many factories had late-night shifts and the Workshop of the World needed workers no matter the time. But as the industrial economy shuddered to a halt, such hours were no longer perceived as a necessity. In 1991 post-midnight trains were replaced by Night Owl buses, which traced the routes of the city’s two principal subway lines.

But the Night Owl buses were not popular with the late crowd. Factories were no longer running 24 hours a day, but plenty of service-sector employers kept their employees on well past midnight. Photographer Conrad Benner grew up in Philadelphia and in his teens and early 20s he worked at a series of jobs that required a Night Owl bus home.

“When I worked in the Old Navy in The Gallery [a partly subterranean shopping mall downtown], they had us do monthly inventory until 2 or 3 in the morning,” Benner says (his next job was at an upscale coffee shop and bar that stayed open until after midnight most days of the week). “It was not fun. But you know what was even less fun? Waiting on the corner of 8th and Market for 40 minutes for a bus that would end up being packed. That was horrible.”

A poster advertising new public transportation hours. (Photo: SEPTA)

Earlier this year Benner started a Change.org petition to demand the return of 24/7 service, and very soon thereafter SEPTA announced its weekend experiment. (SEPTA spokespeople say that the agency had been studying the possibility for a while, but were aware of Benner’s efforts, which had beengaining media attention.) After extending the 24-hour weekend service through November, the agency announced that due to the “overwhelming popularity of weekend overnight subway service pilot … SEPTA has decided to extend the program indefinitely.” The ridership average has been about 15,000 per weekend (prior to the beginning of late-night weekend service the two lines had an average daily ridership of 320,000 between, roughly, 5 a.m. and midnight).

SEPTA has not conducted any polls of their late-night ridership, so they have no idea what proportion of these trips are revelers and which are workers (no doubt some are both). But many of the busiest stops are not in locations known as nightlife hotspots. Bookending the Market-Frankford line are the 69th Street station, across the city border in multi-ethnic Upper Darby (520 entries), while Frankford Transportation Center (400 entries)is located in a Philly neighborhood transitioning from working-class white to predominantly African-American. 52nd Street Station (190 entries) is situated on a dilapidated boulevard that used to be known for its black nightlife, but now hosts only a few neighborhood bars and fast-food joints. On the Broad Street Line the two largest ridership totals are in Olney (360 entries), another lower-income and largely African-American neighborhood, and one of Temple University’s stops, Cecil B. Moore (350 entries).

“I think it’s great, it runs all night for only $2.25,” says Hana, a young African-American woman in nurse scrubs. “It’s much easier and a lot faster.” Diavanna, another young African-American woman in a McDonald’s uniform, works at Franklin Mills, a gargantuan mall in the far northeast of Philadelphia. “I get home much faster because the trains run all night.” Asked how she heard about the new service, she gestures out the window. “I learned about it from the signs.”

The advertising for the 24-hour weekend service is tailor-made for the cocktails and concerts set. . “I haven’t had a chance to ride the overnight yet, but I’ve asked some of our other employees who have and everybody says it’s a mixed crowd for the most part, a combination of millenials going out, college kids, and the usual urban crowd that rides the subway,” says SEPTA’s Smith.

Some of SEPTA’s advertising includes late-night workers, but the general theme is clearly oriented toward those who are out on the town. That’s fine: The message is clearly getting out. There are, on average, close to 6,000 more people riding the trains than took the Night Owls (which still run on the weeknights, with an average ridership of 4,394). The benefits to public safety are just as great regardless of a rider’s purpose: Driving home exhausted at the end of a shift is probably almost as dangerous as drunk driving. (There have been few, if any, reported criminal incidents on the late-night service.)

SEPTA has no plans to return to the 24/7 service, which is currently only enjoyed in New York and some lines in Chicago. (Although other services have been experimenting with pushing their weekend hours later, there seem to be no immediate plans for 24/7 or even 24-hour weekend service outside of those cities that already have it.) But the low-wage service sector and the health care industry are two of Philadelphia’s (and America’s) largest employers and both are known for late-night scheduling. No doubt the numbers would not be as impressive for weeknight ridership and the beneficiaries are less likely to be millennials, but it would surely make a huge difference to those who must now rely on the hated Night Owl buses.

“I’m in a different part of my life where it doesn’t necessarily benefit me as much as it would have when I was 16 or 22 and working at those jobs and trying to drink more,” Benner says. He hopes SEPTA will eventually run the trains all night every day of the week. “That makes the most sense because it’s not just benefiting people going to bars and restaurants. My [restaurant] job didn’t end at midnight just on Fridays and Saturdays; it ended on midnight or 1:00 every night of the week.”