Between 1960 and 2016, inflation-adjusted median rents in America increased by 61 percent and median home values increased by 112 percent, according to a recent report from Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. Median incomes, meanwhile, increased by only 5 percent for renters, and 50 percent for homeowners. In a new report, Urban Institute researchers Corianne Scally and Dulce Gonzalez look at how Americans are managing these trends.

This striking divergence in the growth of housing costs and incomes has led to a predictable outcome, even as the economy has slowly recovered from the Great Recession: more and more Americans are struggling to make rent. The percentage of renters who are considered to be “cost-burdened” (meaning they devote over 30 percent of their income to housing) increased from 23.8 percent in the 1960s to 47.5 percent in 2016, according to JCHS. A recent report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition concluded that there’s not a single county, metro area, or state in the country where a full-time minimum-wage worker could afford a two-bedroom home.

“Housing is the biggest monthly expense for most households,” Scally says. “It happens regularly, and it’s due every month whether you rent or own—and more households are facing challenges with this as housing costs have gone up over the years, and incomes have really stagnated.”

To date, quantitative research on the effects of the rising cost of housing has been relatively sparse, even as Harvard sociologist Matthew Desmond’s extraordinary ethnographic study of poverty and housing insecurity (and growing body of related research) has demonstrated just how pernicious and far-reaching the effects of a lack of affordable housing are for children and families. As Scally points out, existing surveys and cross-sectional data make it difficult to draw causal links, so it’s impossible to say with certainty that a person isn’t eating enough or isn’t going to the doctor because they’re spending all their money on rent.

In December of 2017, however, the Urban Institute launched the Well-Being and Basic Needs Survey, an annual survey with the explicit goal of assessing and tracking “individual and family health and well-being at a time when policymakers seek significant changes to programs that help low-income families pay for food, health care, housing, and other basic needs.” Scally and Gonzalez rely on this data source to paint a grim picture of the struggles facing many Americans today.

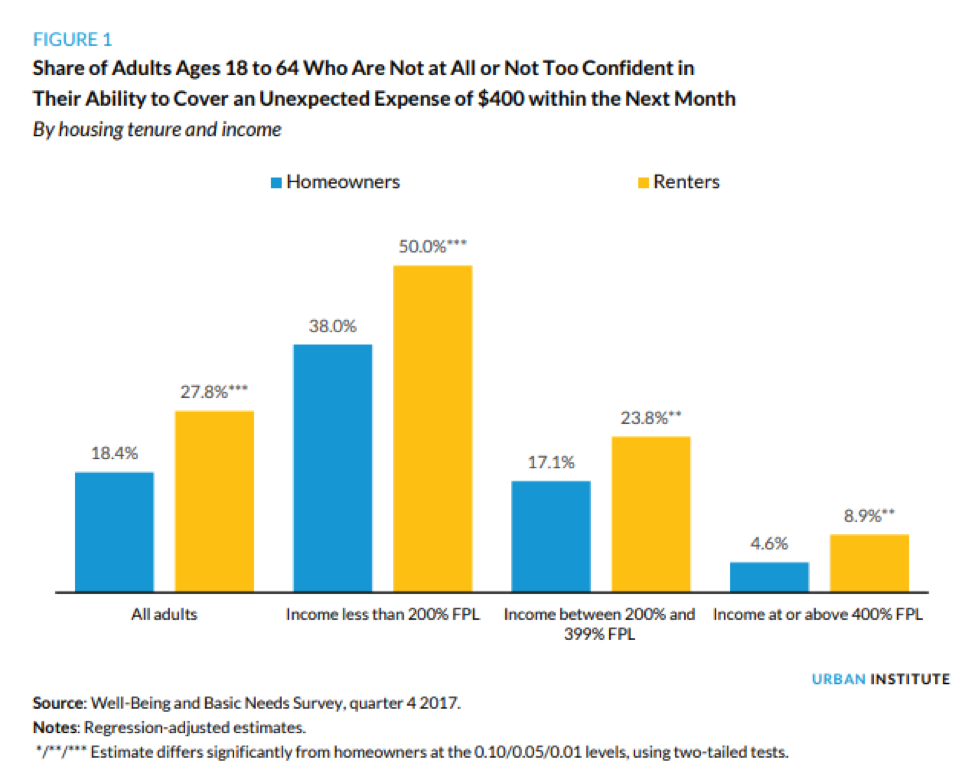

Approximately one in four renters in the United States, and 50 percent of Americans earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line, say they’re not confident in their ability to “cover an unexpected expense of $400.” In comparison, only 18.4 percent of homeowners express a similar sentiment. Somewhat surprisingly, even wealthier renters express more concerns than wealthier homeowners about their ability to cover financial emergencies, as the chart below, from the report, illustrates:

Almost 9 percent of renters earning more than 400 percent of the federal poverty line lacked confidence in their ability to cover an unexpected expense. Renters were also more likely to report experiencing large, unexpected declines in their income than homeowners.

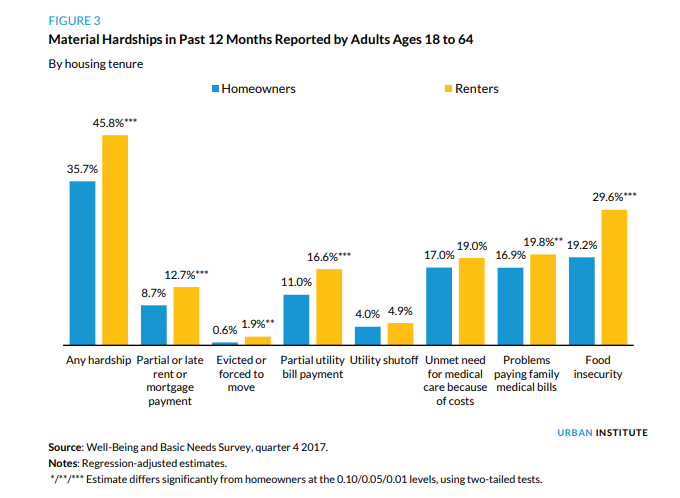

Meanwhile, as the chart below illustrates, the share of both renters and homeowners reporting some kind of material hardship—defined as either paying their rent/mortgage late or making only a partial payment, being evicted or forced to move, paying only a portion of their utility bill, having their utilities shut off, having an unmet medical need, having a problem paying medical bills, or experiencing food insecurity—is staggering.

Almost 46 percent of renters, and 35.7 percent of owners, reported experiencing some type of hardship in 2017. The percentage of Americans experiencing food insecurity—29.6 percent of renters and 19.2 percent of owners—is particularly jarring. Even higher-income Americans reported facing various types of hardship—7.3 percent of homeowners earning more than 400 percent of the federal poverty line reported experiencing food insecurity, while 8.3 percent reported problems paying medical bills. (Only 3.9 percent of those homeowners reported a late or partial housing payment.)

In the U.S. today, less than 25 percent of eligible American households receive federal housing assistance. In some cities, the wait for Section 8 housing vouchers can take years. The Trump administration has proposed deep cuts to federal housing assistance, as well as the imposition of work requirements on beneficiaries. To Scally, the higher percentage of renters and owners reporting food insecurity than reporting a late or partial housing payment tells a powerful story—one about how Americans are resolving the conflict posed by stagnant incomes and the ever-rising cost of housing.

“You have to pay for your housing every month—if you miss a single payment, it jeopardizes the very roof over your head,” Scally says. “Whereas food budgets—people can make discretionary decisions on a monthly basis. They can buy a little more, they can buy a little less. Adults can choose to go hungry and give a little more food to their children. But those are terrible tradeoffs to make.”