Access to financial services in the United States, like most everything else in this country, is highly unequal. According to a 2015 survey by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, approximately 7 percent of American households are unbanked (meaning they have no checking or savings account), and an additional 19.9 percent are “underbanked.” The percentages are higher—approximately 50 percent—among both low-income and minority households.

While some of this is driven by consumer preferences, economists at the New York Federal Reserve have also found that people in low-income neighborhoods “are more than twice as likely to live in a banking desert than their counterparts in higher income tracts” and “have become somewhat more likely to live in a banking desert since the crisis.” (Branch closures have also affected higher-income neighborhoods.)

Financial technology, or “fintech,” has been touted as a possible solution to this dilemma. These products don’t require a physical branch—customers can make deposits, pay bills, and transfer money on their phones. And at least some of these products have the potential to reduce the costs associated with some financial transactions—sending remittances, for example.

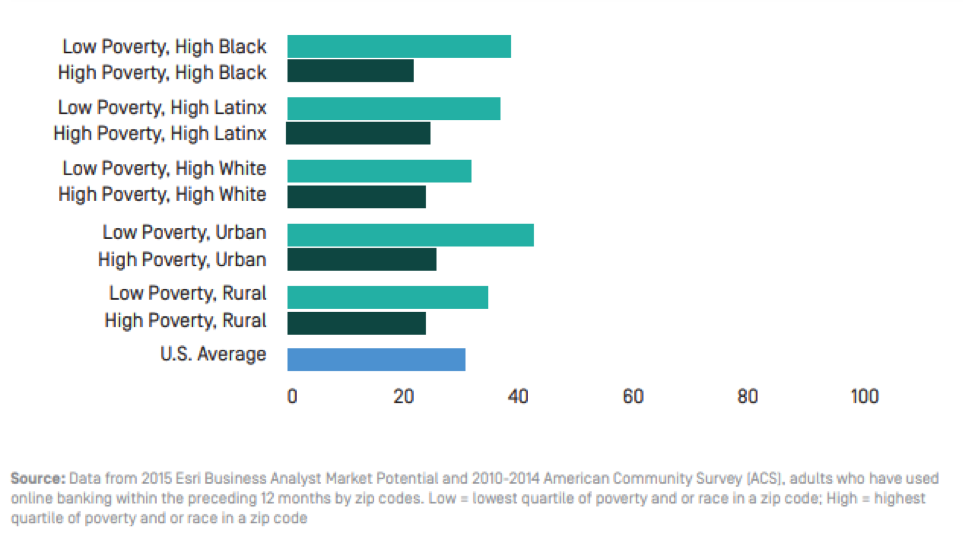

But a report published this week by New America suggests that fintech still has a ways to go in terms of access. For starters, low-income households are still less likely to have high-speed Internet in their homes or to own a smartphone. To wit: Only 58 percent of adults in poor, rural communities have high-speed Internet at home. Perhaps not surprisingly given these barriers to access, disadvantaged groups are also less likely to have used online banking services in the past year, as the chart below (from the report) illustrates:

While approximately 22 percent of adults in high-poverty African-American communities have used online banking services in the past year, a significantly higher percentage (39 percent) of adults in wealthier black communities have used the technology.

“Lower-income white communities, communities of color, and rural communities do not currently have access to fintech or are not using fintech to make financial transactions—at least, often not at the same rates as more advantaged communities or at rates that suggest fintech is compensating for underserved communities’ limited access to financial services,” concludes Terri Friedline, the report’s author.

As Friedline points out, simply expanding Internet access could go a long way toward erasing these gaps, as could supporting community and non-profit providers in efforts to develop fintech offerings and programs that reach more consumers. Until then, though, fintech is falling short of its promise as a great equalizer.