On Tuesday, Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) unveiled a number of significant changes to the Senate’s tax reform legislation. Most of the tweaks were designed to ensure that the bill complies with the Senate’s “Byrd rule,” which requires that legislation not add to the deficit after 10 years.

In the latest version, the corporate rate cuts would remain permanent, the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate would be repealed, individual rates would be lowered by a bit more than the Senate’s previous bill, the standard deduction would increase, and the value of the child tax credit would increase to $2,000 (from $1,650). But most of the changes affecting individuals—both the cuts to the individual tax rates and the elimination of many of the deductions individuals claim—would expire after 2025. The bill would, however, continue to index the individual tax code to the chained Consumer Price Index, a slower measure of inflation, which means that more families would more quickly be pushed into higher tax brackets than under current law.

“Essentially, what happens in 2026 is we’re transported to an alternate reality where TCJA had never happened (on the individual side … the corporate cuts are permanent) except for keeping chained CPI,” explained Ernie Tedeschi, a former Department of the Treasury economist who’s been modeling the effects of tax reform legislation.

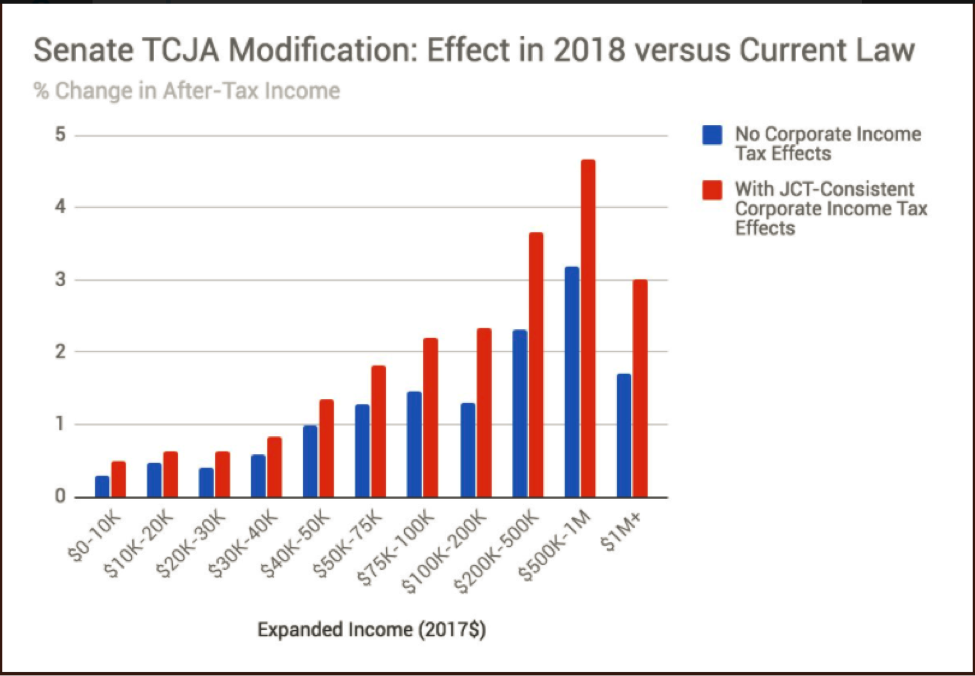

Here, according to Tedeschi’s analysis, is what the new version of the Senate’s legislation means for taxpayers in 2018, as compared to current law:

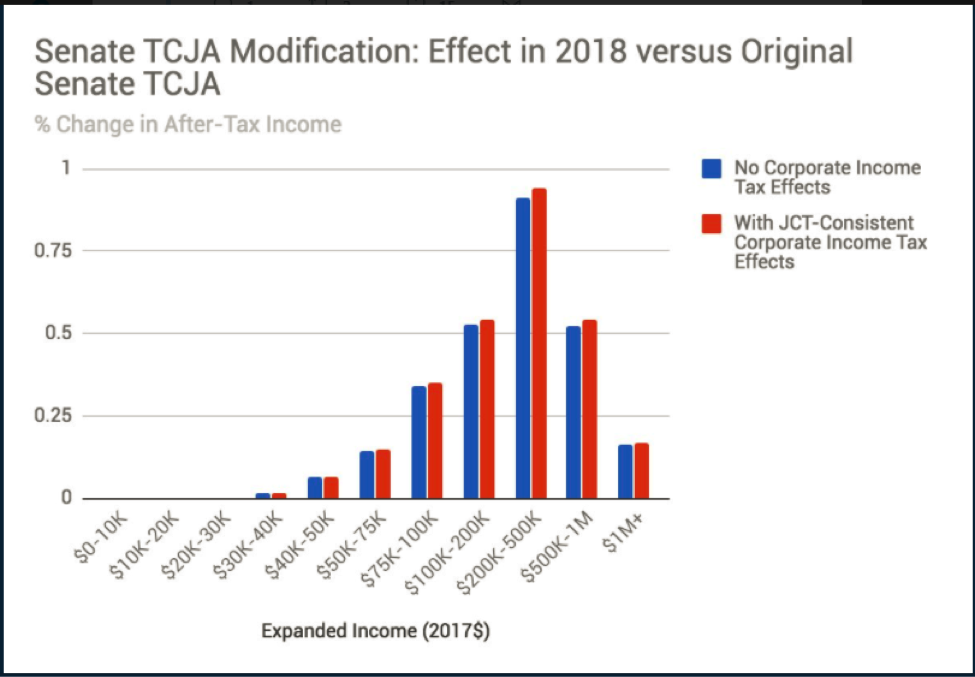

In 2018, pretty much every income group fares better under this modified version than under the Senate’s original bill released last week, as Tedeschi’s chart below illustrates:

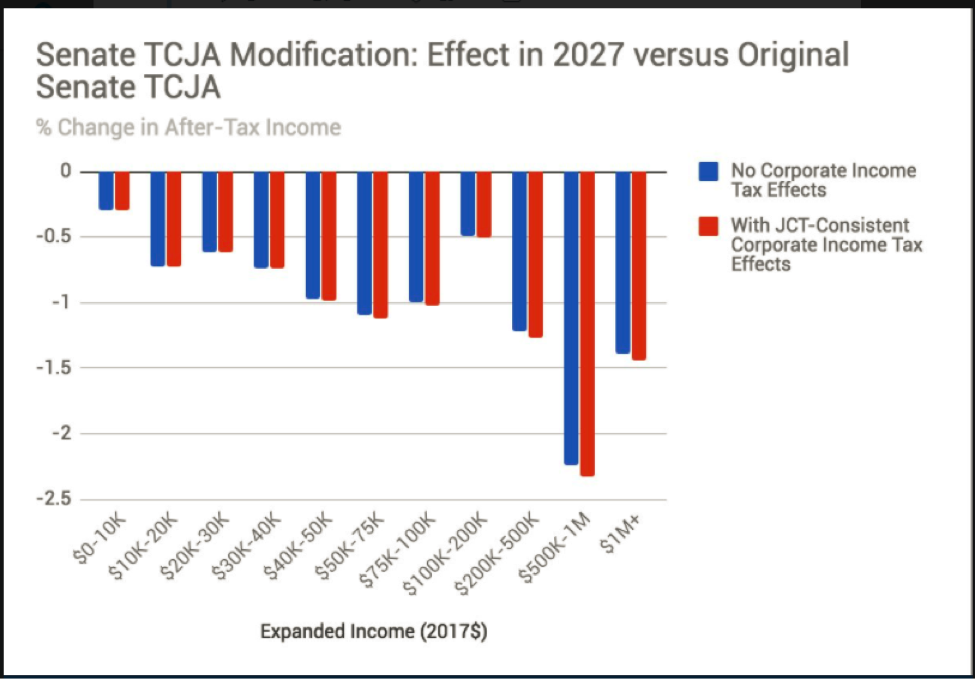

In 2027, however, every income group looks quite a bit worse under the revised version, as compared to the previous version, as the chart below (also from Tedeschi) illustrates:

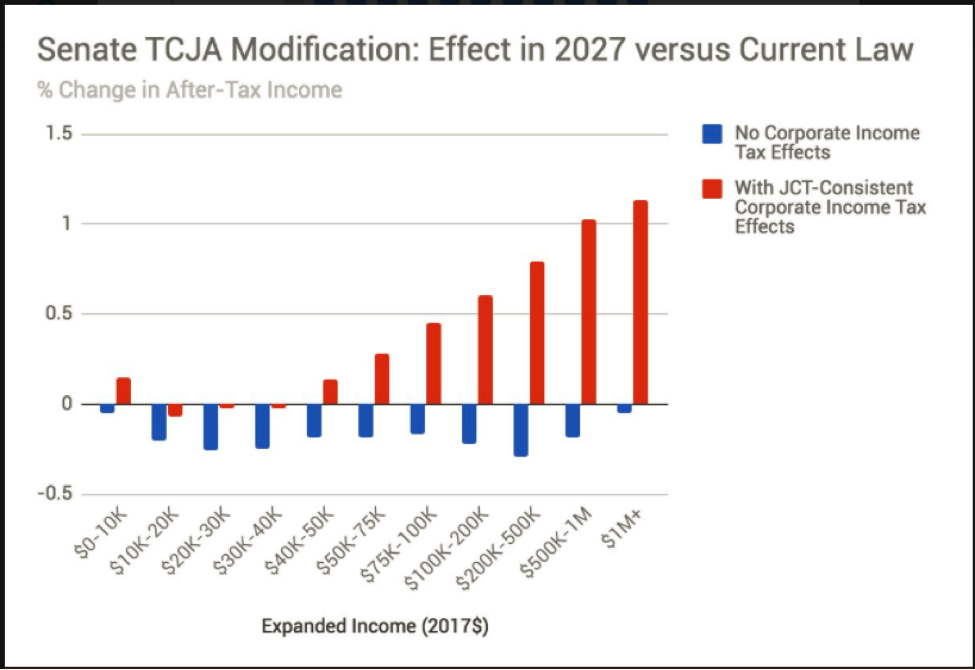

And here’s how different income groups would fare under the revised Senate bill, as compared to current law:

As with previous versions of both the House and Senate legislation, a sizable portion of Americans would also see their taxes go up in 2027, as compared to current law—about 38 percent, if the effects of corporate rates are factored in; or 72 percent, if those effects aren’t factored in. Tedeschi calculates that parents of children under the age of 18 would be particularly vulnerable under this revised bill. Even after including the effects of the corporate cuts, by 2027, 47 percent of all parents, and 70 percent of parents earning between $10,000 and $50,000, would see their taxes increase in 2027.

Republicans have argued that they expect the changes to the individual tax code to ultimately be renewed.