Sometimes I feel like I’m the only one who remembers Kozmo.com, the start-up that delivered snacks to your home or business by messenger in the late ’90s.

Does that sound familiar? Or maybe you’ve heard of Fresh Direct, which has been delivering groceries to New Yorkers for more than a decade? Or temp agencies? Have you heard of temp agencies?

The current frenzy over “the sharing economy” makes it seem as though on-demand delivery services and exploitive freelance labor models are new.

The current frenzy over “the sharing economy,” “the gig economy,” “the 1099 economy,” “the on-demand economy”—whatever you want to call it—makes it seem as though on-demand delivery services and exploitive freelance labor models are new. These labels are convenient for the kind of technology industry marketing that frames every company as a unique innovation in order to convince investors to invest and consumers to consume, and for journalists who need to write about new trends in order to convince editors and readers that they matter. Even the most passionate detractors of sharing, gigs, and 1099s have a vested interest in acting like this is a horrifying expression of new technological forces, in order to build energy around regulation and labor reform.

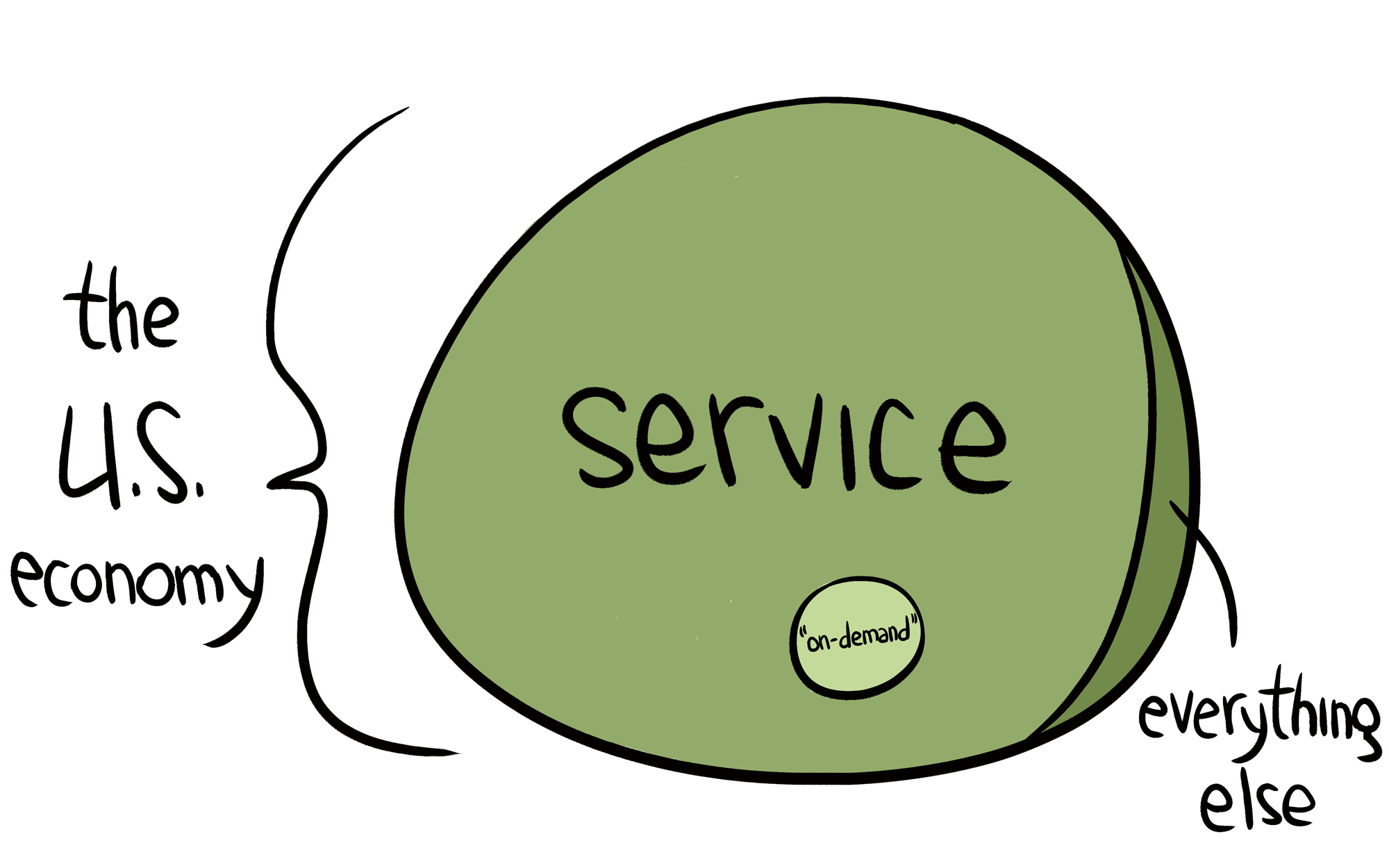

But this is not new. Service economy + smartphones = service economy.

For decades, the service sector has comprised the bulk of job growth in the United States. This includes lawyers, doctors, and accountants, but mostly it is low-wage service workers who now make up more than 84 percent of U.S. employment. Since 2010, the top five fastest growing occupations have been service jobs, and four of them have a median annual wage of $21,000 or less.

Is Dominos a tech company now that it has an app?

Technology has had a hand in widening the wealth gap and eliminating much of the middle-class since this industry shift began decades ago. But with the other hand, tech scoops up and delivers old promises of middle-class life and delivers them to the new poor. It’s cheaper to eat out, to shop, to entertain yourself, and to obtain consumer technology that makes all those things even more convenient, even on just $21,000 a year. A knowledge economy is sometimes referred to as “an economics of abundance, not scarcity.” It’s really an economics of scarcity with the appearance of abundance.

“On-demand economy” services are essentially the latest iteration of e-commerce meeting the latest stage of low-wage service job growth. The ubiquity of smartphones has made constant consumer connectivity the new normal, and that has smoothed logistics for many different kinds of businesses that face significant distribution and delivery challenges. Is pizza delivery part of the on-demand economy? Is Dominos a tech company now that it has an app? Why are we making these distinctions?

If a freelance labor model is the gig economy’s true innovation, it’s late on that one as well. Independent contract work has been on the rise ever since America shifted away from a manufacturing economy, simply because it’s cheaper. Taxi drivers were freelancers decades before Uber was a misty twinkle in Travis Kalanick’s greedy eye.

Of course, unique moral outrage is seductive. Someone being paid $5 an hour to deliver toilet paper to people who make $300 an hour and are ideologically opposed to tipping does look very gross, lazy, and inhumane, not to mention indicative of a deeply broken economy and an incredibly warped definition of “innovation.” And tech certainly has a rare ability to further the distance between laborers and their bosses, dehumanizing all of this very human service work.

But there are a lot of gross things about our whole economy. What about the less visible service workers who keep Silicon Valley humming despite low pay and bad treatment—the cafeteria workers, the janitors, the bus drivers? To which economy do they belong?

It isn’t that these companies bear no unique characteristics—it’s that forcing them into their own category with hard edges, their own “economy” at that, cuts the ties between them and the rest of the real trends that have been transforming the U.S. economy for decades. We shouldn’t do that if we want to actually understand why and how any of this stuff is happening.

This is one hell of a service economy. But if you want to feel better about your participation in it, don’t wring your hands over 1099s—just go ahead and hire a real servant and pay them decently.

The Crooked Valley is an illustrated series exploring the systems of privilege and inequality that perpetuate tech’s culture of bad ideas.