A few weeks after receiving college acceptance letters, high school seniors are often greeted by a set of follow-up missives, containing details on financial aid package. For many kids, it’s the contents of these later letters that determine which school they’ll be attending.

Unfortunately for those students, trying to make sense of these aid packages can be an exercise in futility, according to a new report from New America and uAspire.

Analyzing over 500 financial aid letters, researchers from the two organizations found that different schools use wildly varying, and frequently confusing, language to describe grants and loans. Among 455 different schools, the researchers documented 136 unique terms for unsubsidized student loans; 24 of those terms didn’t actually include the word “loan.” Fifteen percent of letters referred to Parent PLUS loans as “awards.” Seventy percent of letters didn’t differentiate between different types of aid and provided, in the researchers’ words, “no definitions to indicate to students how grants and scholarships, loans, and work-study all differ.”

Colleges also use official financial aid terminology incorrectly, the report found. In the financial aid letters the researchers analyzed, several different institutions used the term “net cost”—which, according to the federal government’s official definition, is the total “cost of attendance” (COA) at a school minus gift aid (i.e. scholarships and grants)—in a variety of incorrect ways. One school defined net cost as direct costs (which excludes expenses like supplies, transportation, etc.) minus gift aid. Another school defined net cost as direct cost minus gift aid and student loans.

Even the bottom line—the amount of money a student and their family are responsible for paying after financial aid—is often unclear to students, according to the report. Only 40 percent of the letters in the sample actually provided students with this concrete information, and the 194 schools that provided the information calculated it in 23 different ways.

In the absence of clear, high-quality information, it’s easy for students to mistakenly choose a school that’s more expensive than they realize. The lack of clear information is particularly difficult for low-income and first-generation college students. As one such student, at a uAspire focus group in Philadelphia, explained to the researchers: “I’m the first one to go to college, so no one in my family had any idea of what it was supposed to look like. They were all as confused as I was.”

The researchers also conducted a larger, quantitative analysis of 11,000 letters sent to Pell-eligible (i.e. very low-income) students to examine the question of college affordability, an exercise that produced similarly discouraging results. Among Pell grant students, 50 percent of their cost of attendance for college was covered by gift aid, and 16 percent was covered by loans from the institution and federal or state governments. Pell grant recipients had to come up with a third of the total COA—$12,000, on average, for just the first year of college—on their own, via parent loans, savings, or student income.

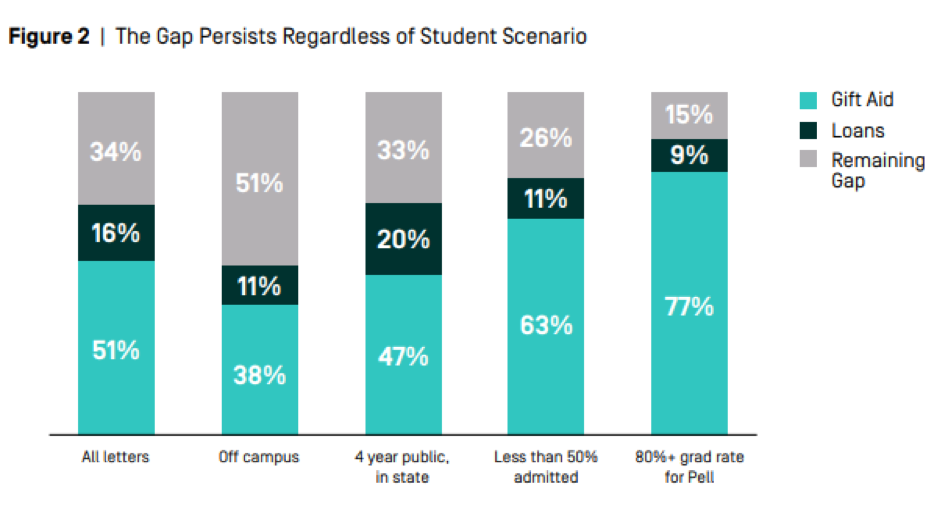

This gap between available financial aid and total cost of attendance persists even among students who live at home, attend lower-cost public schools, or attend selective colleges, as the chart below (from the report) illustrates:

“[S]tudents considered in-state, at four-year public institutions, were still left with $8,400 to cover each year (a 33 percent gap),” the researchers wrote in the report. “Students living off campus still had to cover about $15,000 (a 51 percent gap) for a single year of school. … Students at colleges that admit less than half of applicants were left with over $10,000 to cover (26 percent of costs), and students at colleges that graduate more than 80 percent of their Pell students were left with about $8,000 per year to cover (15 percent of costs).”

When the Pell grant program was founded back in the 1960s, the grants covered almost 80 percent of financial need. Today, the maximum grant covers less than 30 percent of the cost of a degree at a public university. Decades of wage stagnation, historic inflation in the cost of higher education, decreased state funding for higher education during the recession years, and a lack of political will to mount a response have left low-income students with woefully insufficient assistance for college. This research serves as a useful reminder that even smaller fixes could go a long way toward helping students make better decisions about their education.