In 2008, the District of Columbia passed the Pre-K Enhancement and Expansion Act, which sought to make free, full-day, high-quality preschool available to all three- and four-year-olds in the district. The preschools run on roughly the same schedule as the city’s elementary schools, and teachers are paid salaries on par with the city’s elementary teachers. Today, approximately 90 percent of the district’s four-year-olds and 70 percent of the district’s three-year-olds attend public preschool thanks to this legislation.

In a new report, Rasheed Malik of the Center for American Progress, a progressive think tank, reviews the effects of that expansion on a variable that’s sometimes overlooked in discussions about the costs and benefits of publicly funded early childhood education: maternal labor force participation. Malik finds that maternal labor force participation (for women with at least one child under age five) in D.C. increased from about 65 percent (in 2008) to 76.4 percent in 2016; nationally, maternal labor force participation increased by only 2 percentage points during the time period studied.

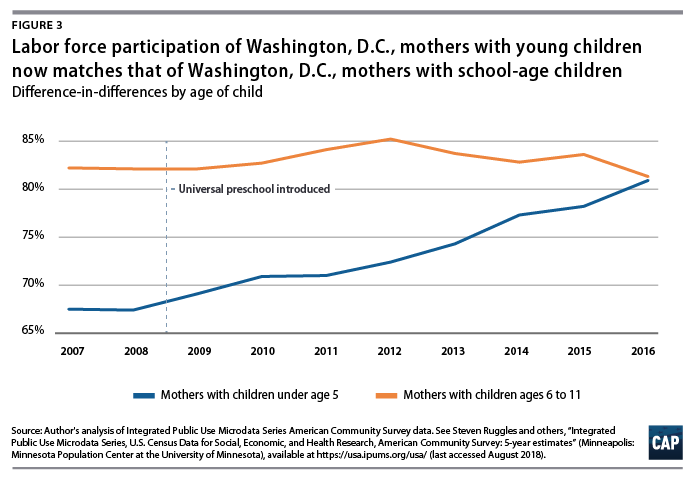

To determine how much of this effect was due to the preschool expansion, Malik performed several analyses, comparing the labor force participation rates of mothers (with a child under the age of five) in D.C. to those of mothers in other big cities in the United States, mothers in neighboring areas, and D.C. mothers with elementary-aged children. Malik found that labor force participation rates for mothers in neighboring areas, as well as rates for D.C. mothers with elementary school-aged children were relatively flat during this time period. Malik ultimately concludes that D.C.’s preschool expansion was responsible for 10 percentage points of the observed increase in labor force participation.

As the chart below, from the report, illustrates, the labor force participation of women with young children in D.C. is now roughly equivalent to that of women with elementary-aged children:

Malik finds that the increases were driven by mothers at the low and high end of the income scale. The labor force participation rate for low-income mothers (those in families living below the poverty line) increased by 15 percentage points between 2008 and 2016, while participation among high-income mothers increased by 13 percentage points. Participation rates for middle-income mothers, which was already quite high (around 75 percent), were roughly unchanged. The effects were also particularly pronounced among unmarried mothers and mothers without a high school degree.

The labor force participation effects documented in this study are, in laymen’s terms, huge. They’re also a bit at odds with previous studies in the U.S.—two previous evaluations of universal preschool programs in Oklahoma and Georgia found virtually no effects on maternal labor force participation.

As the CAP report points out, however, those programs do not serve three-year-olds, are not all full-day, and boast significantly lower participation effects. Studies of universal child care programs in other countries, meanwhile, have found significant effects, ranging from a 2.1 percentage point boost in England (from 15 hours of free childcare for three-year-olds) to an 8.8 percentage point boost in Chile (from free, full-time child care for children under the age of five).

Childcare costs in the U.S. have risen dramatically over the last decade and now represent a significant cost burden for families across the income spectrum—a CAP report published in 2015 pointed out that center-based childcare costs more than college tuition in 31 states.

These costs have real consequences, both for individual women and their families and the U.S. economy. Female labor force participation in the U.S. has been declining in recent years, a trend not observed in other Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries (most of which offer families substantially more assistance with childcare), a fact that economists have warned risks compromising gross domestic product growth. Economists, meanwhile, have also demonstrated that women who leave the workforce when their children are young pay a long-term price.

In recent years, politicians on both sides of the aisle have called attention to the issue and put forth various proposals to make childcare more affordable and accessible. Often, however, proposals to expand publicly funded preschool or other early childhood interventions fall victim to cost concerns. While researchers have already demonstrated that high-quality early childhood interventions can pay for themselves by improving the long-term outcomes of the children served, the CAP report released today suggests such programs have the potential to produce significant economic benefits for affected families as well.