In matching polos, sweaters, and knee-high socks, the teens at Ireland’s Temple Carrig School didn’t exactly appear primed for radical thought on a sunny morning last May. Their teacher, Susan Andrews, tugged them toward deeper reflection, one question at a time. She’d taken a group to the “Humans Need Not Apply” exhibit on robots at the National Science Gallery not long before. Today she reviewed their recent conversation about driverless cars and posed a new question: “What about an AI president?”

The Irish high schoolers began to intuit and reason it out. One student, Grace Holmes, suggested a robot couldn’t be trusted; Andrews asked whether a person truly could be. Another, Orlando Young, offered, “It wouldn’t have, like, empathy.” Andrews had no answer—the students were left to continue mulling the prospect of an empathy-free leader.

Similar questions about artificial intelligence have been daunting the likes of Bill Gates, Elon Musk, and Stephen Hawking. And while countries like France have required philosophy for high schoolers for decades, Ireland is now approaching philosophy with a fresh urgency as societal shifts like self-driving cars loom, engaging tech questions head-on in its new courses.

The recent news of high-profile investor Bill Miller’s $75 million gift to Johns Hopkins University’s philosophy department stunned many Americans, from the spheres of higher education to those in the business community. The donation was pronounced the largest endowment ever given to a philosophy program, which is far less funded in the United States these days than STEM areas like science, engineering, and math. Miller attributed much of his business success to having studied philosophy, and said he wanted to change the subject’s trajectory in the U.S., where politicians like Senator Marco Rubio (R-Florida) have said the country “needs more welders and less [sic] philosophers.”

But a societal respect for philosophy isn’t shocking in Ireland, a place where one of the leading national newspapers, the Irish Times, actually carries a weekly philosophy column, “Unthinkable.” The country counts Edmund Burke (a founder of Irish Republicanism), Francis Hutchison (who helped inspire the American Constitution), and George Berkeley (namesake of Berkeley, California) among its great philosophical thinkers. Now the subject is being championed at the highest levels and introduced to more schoolchildren. “I would definitely call it a movement,” says Andrews, a 20-year teaching veteran who is among its leaders.

President Michael Higgins began calling for philosophy to be introduced to secondary schools a few years ago, citing the need for more critical thinking. Temple Carrig began piloting the first course in 2014. This school year, nearly 60 schools began offering either philosophy electives or philosophy-based modules within other courses. In November, Higgins announced the Irish Young Philosopher Awards, which have drawn applicants from 30 schools.

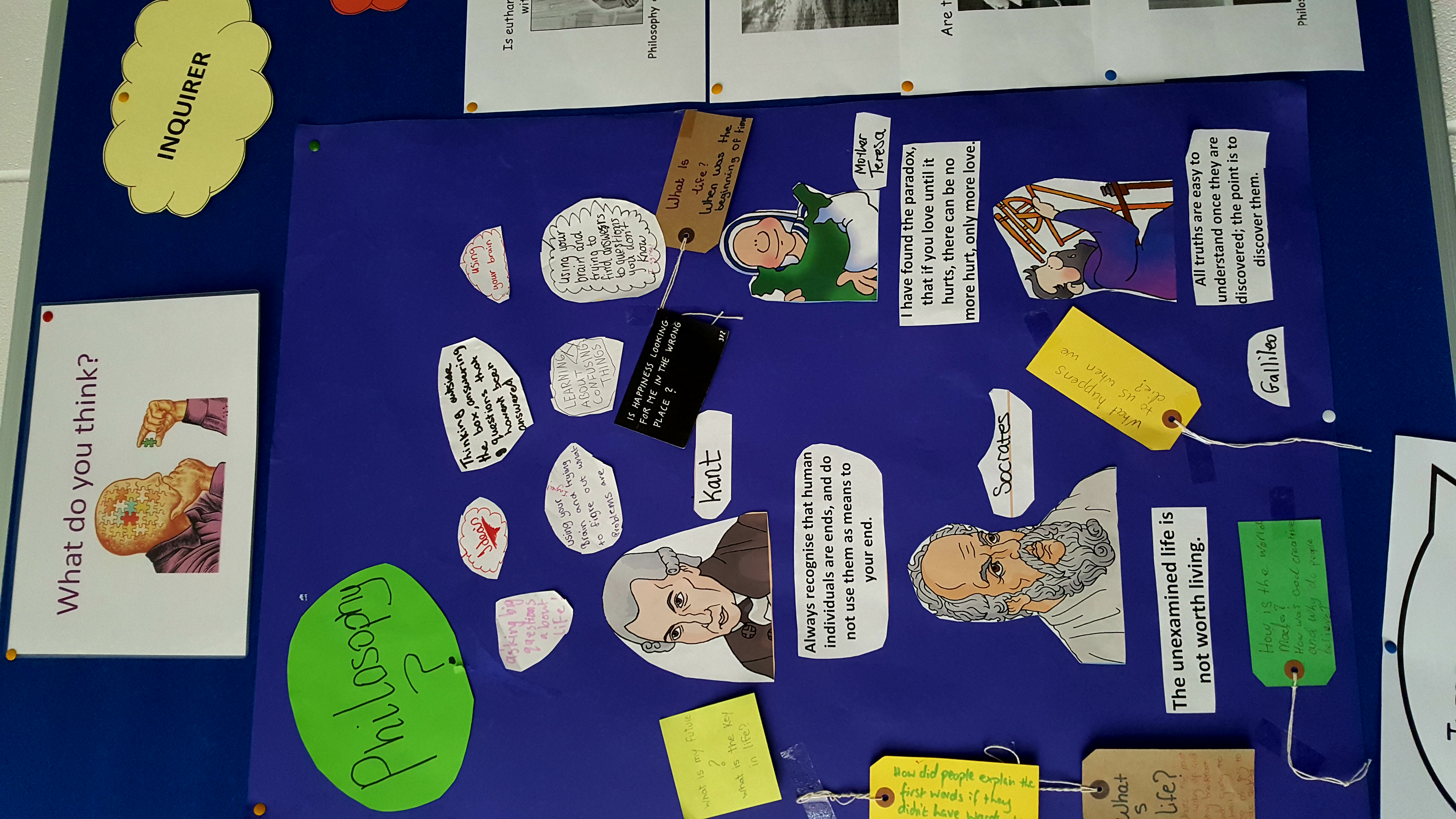

(Photo: Courtesy of Susan Andrews)

Once-rural, tenant-farmed Ireland now sees itself as Europe’s tech capital, hosting the continent’s headquarters of companies like Apple, Twitter, Facebook, and IBM. “Tech has been part of the Irish success story of the past 20 years,” says Joe Humphreys, the Irish Times writer who’s been behind the “Unthinkable” column since 2013.

Seated at one of the newspaper’s conference tables recently in Dublin, Humphreys reflects on philosophy’s place in the country’s history. Before 1922, the biggest question for Irish thinkers always seemed to revolve around independence from Great Britain, he says. With that long since settled, and even the Troubles over Northern Ireland having faded, “the philosophy is coming in on the coattails of the interest in science,” Humphreys tells me. “Critical thinking, logic, independent thinking—those are the skills that will carry you through life.”

So Ireland is going beyond just teaching its tech-minded young people to code. In philosophy courses that introduce not just history’s great philosophers but also the active philosophical-inquiry process, they’re being asked the big questions about business, technology, and human life.

“Philosophy can teach what Google can’t,” the well-connected advocacy group Philosophy Ireland has publicly argued (the president’s wife, Sabina Higgins, is its patron, roughly equivalent to an American board chair). A dozen academics, educators, and activists came together in 2015 to form the group, which campaigned for philosophy to be offered, along with other optional new courses like coding, as part of Ireland’s ongoing educational reform.

Philosophy Ireland’s co-founder, Charlotte Blease, is a pixie-haired young woman who holds a doctorate in philosophy. Blease takes her appeals both high and low: to the parents who worry their kids’ service jobs will be filled by robots, and to those who want their college grads able to conduct interdisciplinary research.

“If you give a shit about technology, philosophy has to be part of it,” Blease says, seated for afternoon tea at the opulent Merchant Hotel, in Belfast. “Ethical issues should be part of the design phase of technology, not an afterthought. As they say in the medical field, prevention is better than cure.”

Among key business leaders, the idea is catching on. In making his gift to Johns Hopkins, Bill Miller told reporters he still employs philosophical inquiry as he considers questions like how societies might adapt to new technology. (Recently he’s invested heavily in cryptocurrency.) Fellow billionaire Mark Cuban, too, told a South by Southwest audience last year that, if he were in college right now, he’d want to be a philosophy major—in part so he could think critically about the dramatic tech and AI wave he sees coming in the next decade. Ireland, the technology hub, has been hearing such signals loud and clear.

The idyllic bedroom town of Greystones perches at the end of the commuter train line from Dublin, along Ireland’s eastern coast. In Andrews’ classroom overlooking the Irish Sea, the faces of Sartre, Aquinas, and Erasmus are posted. Her course supports the idea that philosophy gives a framework for thinking about both business and science. The model Andrews and her Irish counterparts have developed for teaching teenagers philosophy is grounded in history’s most prominent philosophers. Sometimes the high schoolers get so into it that they’ll go around quoting Nietzsche, like college students having late-night dorm-room convos, Andrews says.

The course also employs the Philosophy for Children pedagogy, which encourages active philosophical inquiry on current societal issues. Andrews poses up-to-the-moment questions about business, technology, and society each day. The class discusses models like Steve Jobs as they consider what tech moguls should be doing for society. “Aristotle had some thoughts about that,” she might say after a student suggests his own idea.

Andrews, who also teaches business, has found that philosophy encourages similar skills to entrepreneurship. The 13- and 14-year-old Junior Cycle students who’ve taken philosophy, she says, generate more risk-taking ideas for the business plans they have to develop in her other course. “They’re always trying to think about something a little bit more innovative, more out there, more strategic,” she says.

(Photo: Courtesy of Susan Andrews)

Temple Carrig’s science teacher, Declan Cathcart, and Andrews have also started collaborating. Andrews recently led discussions on the ethics of animal experimentation as Cathcart’s students were studying the lives of wood lice. Cathcart, who teaches biology, chemistry, and physics, praises his students who’ve taken Andrews’ philosophy course. “I’ve never had first-years so well-versed in forming hypotheses and analyzing data,” he says.

The Irish educators hope the philosophical grounding they’re starting to provide will equip students for the future. Still, they concede there is plenty that’s unknown. “The problems they’ll have to solve, the jobs they’re going to have don’t even exist yet,” Andrews says. “If my students came out and were brave enough to ask the difficult questions and adapt to a fast-changing workplace, then I’d feel they’re equipped to consider how we might live together in an ethical way.”