Campus police at private universities are just like everyone else: they pay their taxes, they sleep in on Sundays, and they’re not subject to the Freedom of Information Act. This means that they don’t have to disclose statistics about arrests and stops made, or any of their internal policies.

A newly proposed piece of state legislation might, for the first time, reverse this norm—at least in Illinois. On February 27, Illinois Representative for the 25th district, Barbara Flynn Currie, proposed a bill—HB 3932—to amend the state’s Private College Campus Police Act, on the books and untouched since it was passed in 1992. The act gives campus police at private universities all the powers of municipal police, including making arrests, and sets a minimum standard of training for these officers. In addition, the act details how campus police officers shall be selected and where, both on and off campus, they have permission to patrol. It also bars private campus police from participating in any state, county, or municipal retirement fund, and from being reimbursed for training with state funds.

The proposed amendment states that, “A campus police department subject to this Act shall disclose to the public any information that a law enforcement agency would have to disclose under the Freedom of Information Act.”

A handful of universities in Illinois, including Northwestern and Loyola, operate private police forces. But the University of Chicago’s police department’s lack of transparency has been singled out as particularly problematic due the size of its jurisdiction and allegations of racially profiling community members and students. (I’ve written about these issues with the UCPD before.)

“Dealing with the federal government and the Department of Defense, those aren’t going to be quick and short-term fixes. But in the interim, at the local level, increasing transparency … keeps law enforcement accountable and it’s a major step in building trust within the community.”

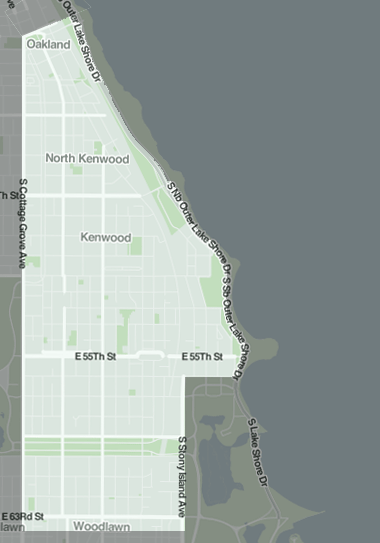

Currie’s district includes parts of the Chicago neighborhoods of Woodlawn, South Shore, South Chicago, Kenwood, and Hyde Park, where the University of Chicago is located. Illinois Representative Christian Mitchell, who also represents parts of Hyde Park, co-sponsored the bill. According to the most recent Census data, 46 percent of Hyde Park residents are white and 30 percent are black. Currie, who received her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from the University of Chicago, spoke with me about the impetus behind her new bill.

“We’ve had a University of Chicago police presence in the neighborhood for many years and I think people are by-and-large happy to have extra pairs of eyes, extra pairs of ears on the street,” Currie says. “But the territory the university police cover has expanded greatly in the last five or eight years.”

Private universities are used to being ranked every which way—diversity, matriculation rates, funding, you name it—but when it comes to private police forces there is little and lean recent data. There is no incentive for universities to release that information. Most universities have some mechanism for internal review of complaints made against their police departments or publish incident reports, but no logs of arrests, stops, and searches.

As such, it is difficult to know exactly how large the UCPD is compared to other private police forces, but based on the information available, it appears massive—not just in numbers of officers but in the size of the jurisdiction it polices. According to the Hyde Park Herald, the UCPD’s hundred or so officers patrol between 37th and 64th Streets, from Cottage Grove Avenue to Lake Michigan. Around 65,000 people live within these bounds, and most of them are not affiliated with the university at all.

This expansion of the UCPD’s jurisdiction was enabled by the same Private College Campus Police Act that gives UCPD officers the privacy protections of an everyday citizen (they can’t be FOIAed, but can be converted into heaps of metadata by federal employees). Under the act, private universities can expand their policing jurisdiction, “for the protection of students, employees, visitors and their property, and the property branches, and the interests of the college or university.” As the result, the borders of UCPD territory are marked by a series of charter schools it operates at some distance from the campus.

“This is not primarily about a force that operates within the physical confines of the campus,” Currie says, “because the university operates charter schools some 30 blocks from the main campus, all the area in between is subject to UCPD policing.”

The newly proposed legislation would not affect the borders of UCPD jurisdiction, nor halt the legal privilege by which the university may augment its private police presence in the surrounding communities.

Getting the bill passed will be “an uphill battle,” according to Currie, but she hopes that, at the very least, it will open up a discussion. “The argument they will make is we’re private they’re not public so should not be subject to the act. And my counter-argument is that they’re taking on what is ordinarily a very public responsibility, that is, acting like a municipal police force.”

The discussion around private police powers, and in particular those of campus police has been building power for some time in Chicago. In October, a community forum on the role of the UCPD was held at the Experimental Station in Hyde Park, in which several community members attested to being profiled by university police. According to first-year University of Chicago undergraduate Nicolas Aldape, Chicago Alderman Leslie Hairston announced at the forum that she planned to form a task force to investigate the issue.

Aldape has been a member of the University of Chicago student-run Campaign for Equitable Policing practically since he arrived on campus. Members of CEP have been working since 2012 to end racial profiling by the UCPD and make the department more accountable to the community in which it operates.

CEP has been attracting interest from students at other Chicago universities too. “As the year has progressed we’ve heard from other schools and other community organizations that it’s something they also want to work on,” Aldape says.

Aldape told me that the bill is an encouraging new step, though there are other aspects of police transparency it doesn’t address, such as a community-run mechanism for reviewing and checking police misconduct.

Currently, the University of Chicago operates an Independent Review Committee for the UCPD, which investigates complaints made against the department. The committee is made up of three students, three faculty members, two staff members,. and three community members. All of the committee members are appointed, however, by the university provost, despite the fact that the majority of people policed by the UCPD are not affiliated with the university.

Racial profiling of students, faculty, staff, and community members by private campus police has, as of late, received special attention. In January, a Yale campus police officer drew his gun on third-year undergraduate, Tahj Blow, who he claims matched the description of a burglary suspect. Tahj is the son of New York Times columnist Charles Blow, so Yale got a few weeks of bad publicity. An internal investigation found no wrongdoing on the part of the officer.

Instances of profiling have been documented at Vasser, Arizona State, the University of California-Los Angeles, and several other universities, both private and public.

Campus police departments have also been criticized for accepting excess supplies, including military-grade weapons, from the Defense Department through its 1033 program. The Pentagon-to-university pipeline was unearthed by Muckrock, which has been releasing a steady stream of FOIA’d documents showing exactly what kind of equipment and how much of it has been funneled to campus police departments (public campus police departments are subject to FOIA).

In October, the social justice non-profit Million Hoodies launched a campaign to demilitarize police, including campus police. The campaign notes that “the War on Drugs and War on Terrorism … equipped local and campus police departments in the U.S. with weapons of war.” The bulk of these homeland security hand-me-downs are not, however, military-grade weapons but everyday law enforcement supplies, which generate far less outrage, if any at all. As with the problem of transparency, the debate around campus police militarization often employs standard public police operations as the measure of how university police should act.

Pete Haviland-Eduah, policy and communications director for Million Hoodies, says he’s in favor in the legislation and that it aligns nicely with the goals of his organization’s demilitarization campaign. “We’re transcending that line from a private institution to having that be a public good,” Haviland-Eduah says. “And the public deserves transparency and accountability from those who are policing them.”

Local reforms, such as the one being proposed in Illinois, Haviland-Eduah suggests, can have an immediate, positive impact on police forces and the communities they patrol. “Dealing with the federal government and the Department of Defense, those aren’t going to be quick and short-term fixes,” he says. “But in the interim, at the local level, increasing transparency … keeps law enforcement accountable and it’s a major step in building trust within the community.”

Everyone I talked to for this story echoed this last sentiment—a wish to improve police-community relations. It’s the same rhetoric we hear from police departments across the country, from Ferguson, to Los Angeles, to New York City, where Commissioner William Bratton used it as part of his justification for requesting additional NYPD officers. This is, perhaps, the most striking example so far of how campus police are becoming just like everyone else.