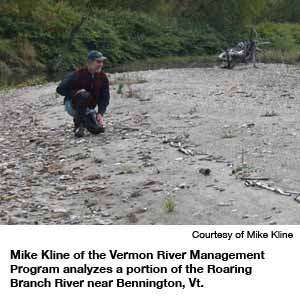

Mike Kline ambles across the highway atop the Park Street Bridge, toward the guardrail overlooking the Roaring Branch River. It’s early summer, long after Vermont’s mountain snow has melted, so the sometimes-mighty waterway is now just a stream piddling between tree-lined banks and stony riprap.

Though I can barely hear the river above the buzzing motorcycles, Kline tells me locals dubbed it the Roaring Branch for a reason: During storms, huge boulders barrel down the river, slamming against each other to produce a thunderous sound. The boulders and sediment move with so much force, they alter the landscape overnight. “It’s actually kind of scary because it’s so powerful,” says Kari Dolan, one of two Vermont River Management Program staffers along for the ride.

Kline has brought me to Bennington to illustrate what this river — with the help of human stupidity and millions of dollars — has wrought: an island.

It’s an ugly land mass in the middle of the river, filled with craggy rock, bushes and Japanese knotweed. The aggradation begins perhaps 200 feet to the north, continuing underneath the bridge and then down the stream, well past the southern side. A few feet away stands a crumbling U.S. Army Corps of Engineers floodwall, constructed mostly from dredged riverbed gravel as part of a process to widen the channel and protect the bridge from flooding.

Instead, the overwidening set in motion events that resulted in this ungodly accidental island, so tall that Kline can almost touch its bushes from the side of the bridge.

A kindly, 50-ish man with a graying moustache under a faded, blue ballcap, Kline rests one arm on his belly, motioning toward the island with the other. “As this builds and builds,” he says, “the river can outflank all the levees and berms.” Every decade or so, the Roaring Branch floods, sometimes jumping its banks. The next time that happens, the river will likely choke the channel, rise above the highway bridge and head into town. It just might take a few houses with it.

Bennington’s flood-threatened bridge is a prime example of a glaring but barely addressed problem: America’s rivers flood, and in trying to protect against the threat, Americans and their governments actually make the floods worse. As a result, each year billions of dollars and several lives are lost, with many more upended. Though climate change is intensifying the crisis, at its root are outdated science, leadership deficits, decisions that prize short-term profit above all and the misguided belief that man can indefinitely restrain something as powerful and relentless as water.

Vermont, a state with a smaller population than the city of San Francisco’s, has become a leader in the effort to reduce the costs of flooding through unconventional means: ripping out levees to let rivers flood naturally and providing towns with financial incentives to discourage building in floodplains. Cities from Charlotte, N.C., to Portland, Ore., have taken similar actions, and comparable concepts are percolating inside federal agencies. There’s no shortage of people who know exactly what’s wrong — and how to fix it. But once floodwaters recede, politics and the desire to live on the waterfront trump sound thinking. Here’s how a relatively small group of people brought common sense to Vermont.

Anyone with a television is familiar with the devastation wrought by 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, but coastal storm damage is only half the problem. Rivers were a major reason flood damages in the U.S., which averaged $3.9 billion per year during the 1980s, doubled during the decade from 1995 to 2004. Government figures don’t draw a distinction between coastal and riverine areas, but at least 9 million homes and $390 billion in property are at risk of a flood with a 1 percent annual chance of occurring — and many exposed residents can’t afford to buy insurance.

Every part of America with a river running through it seems to have a recent flooding horror story: In June 2008, storms struck the Midwest causing $15 billion in damage and at least 24 deaths in several of the 31 states drained by the Mississippi River. Roads closed in Illinois, rail lines were washed out in Wisconsin. In Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the river crest rose 9 feet above the city’s 22-foot-tall levees, a height that the Federal Emergency Management Agency had predicted it would reach just once every 500 years.

In Washington state, late-2007 floods shut down Interstate 5, and waist-deep water forced Seattle firefighters to use rafts to evacuate apartment buildings and houses. For several days during the past two summers, heavy rains closed Indiana’s Borman Expressway, a busy interstate and key trucking route to the East and between Canada, the U.S. and Mexico.

American landowners have long piled up riprap (rock used to armor banks) and built crude levees, the sloped walls aimed at holding back rushing water, but modern efforts to tame watersheds began during the 1920s. Following severe events like the great floods of 1927, which drenched areas from Cairo, Ill., down to the tip of Louisiana, and 1937, which put two-thirds of Louisville, Ky., under water, federal agencies, including the Army Corps of Engineers and President Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, began using big yellow machines to create ever-more-sophisticated structures. This was the era of channelization — construction that eliminated rivers’ natural curves, straightening them into artificial canals. The goal was to keep river basins safe for economic development: agriculture, industry, homes, roads, rail lines.

As Kline explained to me on the drive down to Bennington, while we swung around winding roads and kelly green foothills, Vermont was no exception. During the latter half of the 20th century, it spent $20 million annually to keep its rivers straight and under control, only to see structures fail during increasingly common floods. Beginning in the 1980s, the state experienced about one federally declared flooding disaster per year.

“We were trying to feel good about ourselves, but all it was was glorified property protection,” Kline says.

Kline moved to Vermont in the early 1990s, after two decades as a Colorado river ecologist working in the standard build-to-protect paradigm. Soon after he arrived, Vermont experienced a series of major floods, as rivers took back areas wrested by channelization. Once-sleepy summer-home towns and agricultural villages were now home to businesses and full-time residents, so damage was extensive. Repair costs between 1995 and 1998 totaled at least $60 million. In tiny Vermont, that meant an average expense of $100 per resident, roughly three times as much per capita as Hurricane Katrina cost America.

What struck Kline, then the state’s lead river scientist, and Barry Cahoon, then its lead river engineer, was a cost-benefit paradox: The state had been spending more and more public resources to protect levees and other flood-control structures, but the cycle of flooding was worsening.

The seeds of reform were sown when the pair attended a course taught by Dave Rosgen, a controversial restoration expert who runs classes through his Fort Collins, Colo.-based Wildland Hydrology Consultants. Rosgen is among the most vocal proponents of fluvial geomorphology, a river science theory that spent decades relegated to academic backwaters. At the time, the field was almost wholly reliant on the traditional water science of hydrology, which does a reasonable job of explaining floods from inundation — when waters slowly rise and damage low-lying structures. Such mainstream thinking, though, puts little emphasis on erosion, the scourge of flash flood-prone states like Vermont. Fluvial geomorphology, which studies how water moves earth in its path, offered a way to understand the recent wreckage.

As Kline describes it, rivers carry water and sediment, such as sand, and nature “wants” those materials to remain in equilibrium with the shape of the streambed. If everything is functioning well, floods spread into flat valley floodplains, which act as pressure valves. A widened channel may sap the river of its power and cause sediment to build up and aggrade. A river constrained by structures adjusts by incising, or digging down into the landscape, adding speed and power to the stream.

During storms, if a river can’t access its floodplain, fluvial erosion drags away parts of the riverbank. In the worst case, this causes an avulsion: The bank collapses, and the river obliterates anything in its way.

Kline and Cahoon came to the conclusion that all their dredging and armoring and channelizing just increased rivers’ velocities and fueled erosion. In some cases, they could trace current flood damage back to changes made 100 years earlier. But erosion turned out to be just one part of the problem.

Driving around Vermont in a hatchback, with occasional stops to gaze at rivers and levees, is a great way to receive a crash course in why so much of America is so often overwhelmed by floods. Kline’s co-instructors on my journey are Dolan, a mountain-climbing ex-Ivy League lacrosse star who’s done environmental work in cities from Paris to Nairobi, and floodplain management coordinator Rob Evans, a 30-something family man so in love with his job that he makes geeky, endearing wisecracks about federal disaster funding.

The most troubling aspect of the U.S. floodplain management system is that there is no U.S. floodplain management system. The Army Corps builds levees but relies on local governments to maintain them. (Many do a horrific job.) FEMA manages flood hazard mitigation, except in many farm areas, where the U.S. Department of Agriculture takes the lead. Other agencies, such as the Department of the Interior, play minor roles. No one is in charge. Even at the regional level, cooperation is ad-libbed. In the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan’s administration killed the large-scale authorities — such as the Upper Mississippi River Basin Commission — that coordinated multi-state flood-control plans. Federal districts have different policies and goals, despite residing side by side. Cities with enormous levees inhabit land across the river from towns with no levees at all. Decisions are made lot by lot, town by town, with little consideration for cumulative impact throughout a watershed.

A classic case of inconsistent policy involves the St. Louis area, where levees and dikes aimed at keeping the Mississippi River at bay now prevent the tolerable sort of flooding that might dissipate the river’s energy. Outside the city, many agricultural levees were built to withstand a 500-year flood — an event with a 0.2 percent chance (according to FEMA estimates) of occurring in any given year. Yet some levees inside St. Louis are able to withstand only 100-year floods. If a flood strikes between those two levels, farmland levees will keep the river from spreading out into its floodplain, and water might overtop the city levees.

Last year, the river came within a few feet of such a breach, which could do for some St. Louis neighborhoods what Katrina did for New Orleans.

The lack of flood control coordination is one reason the government has such bad data on flood risks. The Army Corps, which manages about 14,000 miles of public levees, doesn’t know how many miles of private levees exist in America; educated guesses put the number somewhere around 100,000 miles. FEMA, part of the Department of Homeland Security, relies on flood hazard maps in Vermont and many other states that are nearly 20 years old, filled with outdated, inaccurate data. Despite a FEMA digital mapping program that spent $1 billion between 2003 and 2008, a recent National Research Council report found that four out of five Americans live in an area where flood maps fail to meet FEMA’s data-quality standards. Few maps account for how erosion might alter the landscape or elevate flood risk.

The map problem is gargantuan. The FEMA-administered National Flood Insurance Program, which insures nearly 6 million policyholders for up to $1.1 trillion in value, is based wholly on these substandard maps. The flood insurance program’s use of the 100-year floodplain as the safety standard — requiring that anything inside the floodplain be insured — has trickled down to state and local government and become the default.

“People believe that if they’re 3 inches outside the 100-year line, they’re absolutely safe. They don’t realize that a 101-year flood is going to get them,” says University of Maryland civil engineering professor and retired Army brigadier general Gerald Galloway.

Though a house inside the 100-year floodplain technically has a 1 percent chance of experiencing a flood this year, it has a 1 in 4 chance of being flooded over the life of a 30-year mortgage. And because the maps are old and climate change engenders severe weather, what used to be a once-in-a-century flood might arrive every few decades. Nevertheless, new construction flourishes within floodplains, spurred by the general longing to live near rivers, developers’ hunger for profits and the government’s willingness to insure homes guarded by levees in dreadful condition.

“People choose to live near rivers because it’s a nice place to live or sometimes because there’s no other place for them to live. We have to deal with that,” says Mike Grimm, acting director of FEMA’s risk reduction division.

Grimm has the stated mission of diminishing flood damage, and his unit doles out more than $200 million per year in mitgation grants, but inside the federal government, he’s in the minority. If America has any philosophy with regard to its rivers, it’s build, baby, build. Around the time Reagan killed the basin commissions, his administration updated federal water project guidelines to make national economic development their chief objective.

Most federal policy flows in that direction: The USDA spends about 10 times as much on subsidies that encourage farmers to expand cropland as it does on conservation programs that might mitigate flood damage. In urban areas, the Army Corps of Engineers spends tens of millions of dollars constructing levees with huge maintenance costs. FEMA offers residents of hazardous areas low-cost flood insurance. Between 1997 and 2006, federal claims paid on repetitive-loss properties — those with at least two flood insurance claims during the span of a decade — more than doubled to a cumulative $7.9 billion, according to the Government Accountability Office.

“If you didn’t insure people to build these things, nobody would be building there,” says Peter Paquet, a wildlife and fish manager at the congressionally mandated Northwest Power and Conservation Council. “People get flooded out, get reimbursed by flood insurance and rebuild right back in the floodplain.”

For the average state floodplain manager, there’s little reason to upset this status quo.

Vermont became a hub for change, in part, because the existing system failed the state so badly. Elected officials there just didn’t understand how towns could be following all the federal rules, but taxpayers kept footing huge reconstruction bills after floods.

Kline and Cahoon believed that erosion was a major culprit, and after years of fruitlessly waving their arms in front of policymakers, they finally had enough real-life evidence to make a case. In 1998, the legislature, with the support of then-Gov. Howard Dean’s administration, asked them to create what would become the River Management Program.

A new organizational structure brought decision-making under one roof, opening new sources of funding to pair with federal hazard mitigation grants. Because river restoration programs bolster water quality and wildlife preservation, Kline and Cahoon could tap federal funds aimed at those pursuits. They also managed to elevate floodplain management from an environmental issue to a public safety concern.

“You can capture a heck of a lot more public interest whenever you’re getting into a situation where a guy is going to lose his farm and fields or the town road is going to fall into the river or a house is teetering on the edge,” Cahoon says.

At first, they followed the advice of experts like Rosgen, who believed that if manmade channelizing caused erosion, something more natural should help. They adopted a method called natural channelization, or bioengineering, which restored rivers to conditions closer to their natural state, with vegetation and sinuosity, or curved paths.

After four or five years of expensive stream restoration, however, it became obvious to Kline that the approach was failing. “No matter how much you try to incorporate these natural watershed processes,” Kline says, “a static channel is a static channel.”

He realized that Vermont’s approach — and the ideas of much of America’s river science establishment — was simply wrong. The best way to deal with erosion, flooding and all the other problems associated with out-of-control rivers wasn’t to manage the river. You just had to give the river enough room to move, change and create its own floodplain, and then get the hell out of the way. “If we leave the rivers alone, in a sense, they’ll fix themselves,” Kline says.

This seemingly radical approach isn’t new. Gilbert White, the father of floodplain management, was advocating human adjustment to river movement as far back as the World War II era. His strategy had just one shortcoming: It was politically infeasible. Long ingrained in the minds of most elected officials, Wildman says, is “the idea that natural systems are a wacko environmentalist approach, and engineered, buildable systems are the solution.”

Under Cahoon, who has since returned to field engineering work, and Kline, now leader of the program, the Vermont flood mitigation effort capitalized on a friendly political climate. First, it combined state and FEMA money to map river corridors, thus far measuring the path of erosion in 8,500 miles of rivers and streams. Unlike most FEMA maps, Vermont’s indicated not just where the river resides today, but where it’s likely to shift in coming decades.

Kline’s team then met with regional planning agencies to prioritize towns with the worst repeat flooding damage. Vermont’s governance is particularly community-oriented, so that team focused on persuading local officials to adopt stringent zoning regulations to prevent building near rivers. The guinea pigs were Bennington, an old New England college town, and Stowe, a prosperous ski resort area with major pressure for new development.

After a lengthy courting process, both implemented model bylaws written by the River Management Program and passed rules limiting building in what were called Fluvial Erosion Hazard Zones, a far larger danger area than federal standards demand.

Three more towns have followed, with 70 more in the pipeline. Since then, Evans and other members of Kline’s unit have helped local officials apply for FEMA funding on flood protection projects. Sometimes, there’s nothing they can do but look after existing structures and hold back new river encroachments. Yet many projects will be not just nonstructural, but anti-structural —removing a levee or even reconstructing a floodplain at a lower elevation to release pressure from the river.

In barely five years, Kline has already seen progress. One example: The USDA has cut back its dozens of riprap jobs per year down to just a handful, saving as much as $1 million annually. The state transit agency used to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars maintaining Route 108 near Stowe; now, it spends almost nothing. The best evidence of Vermont’s success may be emulation: Next-door neighbor New Hampshire recently asked Kline for advice in copying aspects of his program.

Other states and cities have instituted similar endeavors. In North Carolina last year, Charlotte-Mecklenburg County invested $20 million in local, state and federal money to eliminate structures and property in its floodplain. It was the most visible action of a years-long campaign that includes mapping future conditions and regulating open space to manage the flow of water. In parts of Washington and Oregon, after scientists discovered that dams and levees were damaging fish habitats as well as failing to prevent flooding, governments have refocused on restoration.

All these efforts fit under the mantra of “no adverse impact” — the floodplain manager’s equivalent of “first, do no harm” — a renewed effort within the field to restrict development in favor of long-term safety. Such ideas are gaining currency at the federal level, too, albeit slowly. After the 2008 Midwest floods, the Army Corps of Engineers helped create the Interagency Levee Task Force, which is examining long-term mitigation strategies, moving beyond the old default of rebuilding aging levees and erecting new ones. FEMA has begun Risk MAP, another ambitious five-year plan to update floodplain maps with comprehensive data.

“People are seeing, and getting tired of, taxpayer dollars going back into the same types of fixes as before,” says George Riedel, deputy executive director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers. “I think people are really now questioning: Why are we doing this? Why are we going back to places that have flooded two or three times?”

Vermont has made so much progress in spreading the gospel of avoidance, many prominent ecologists, engineers and advocates say it might serve as a model for other states — or at least provide them with useful strategies. Yet for every Vermont booster, there’s a skeptic dismissive of the claim that Kline has anything to say to the rest of America about rivers. Even Rosgen doubts a regulation-heavy approach could fly elsewhere. “Ideally, you’d take everybody out of the floodplain and let the rivers go back to what they were pre-white settlement. That’s not really practical,” he says.

To be sure, while erosion causes upwards of $400 million in annual damage nationwide, it’s a more pressing problem in Vermont and Appalachia than, say, Southern California. There are also obvious cultural differences between Vermont and much of the rest of the country. Yet Kline’s team has repeatedly taken actions that generate political blowback on a big-state scale and effectively faced down detractors.

Back in the car on U.S. Route 7, Kline, Evans and Dolan recount some of River Management’s most contentious recent moves. When the developer of a project combining a retirement community, day care center and moderate-income housing wanted to site a storm water retention pond in the river corridor, they said no. When Bennington approved a retirement development dangerously close to the Roaring Branch, the rivers program took the case all the way to the Vermont Supreme Court — and won. They even stopped an urban farming program for at-risk youth, a sacred cow for left-wing Burlingtonians, from composting in the floodway, helping prompt the state legislature to pass a law exempting compost programs from state regulations. (FEMA is now handling the alleged violations.)

“We get into a lot of these conflicting societal values,” Kline says. “The trump card for us is public safety.”

Outside Vermont, that card might not be playable. There’s a long history of people trying and failing to focus on mitigation or erosion or revamping maps. Most have run into unbreakable political roadblocks, from pro-development small-town mayors to incredulous U.S. senators.

“The issue isn’t knowing what the lessons are. The issue is doing something about the lessons,” says Galloway, the University of Maryland professor. “A dozen reports have come out and identified exactly what the problem is. But the solutions fall into the ‘too hard’ box.”

Of anyone who’s worked on this issue, Galloway has the most cause for frustration. In 1993, devastating floods struck the Midwest. More than 1,000 levees failed, 70,000 homes were damaged and 47 people died, with costs nearing $20 billion. The Clinton administration tasked Galloway with leading a blue-ribbon panel to seek a solution.

Before the Galloway report was even released, Congress embarked on changing federal programs, with an ambitious bill introduced in the Senate in 1994. But after that November’s election, the Republican Revolution happened; floodplain management wasn’t part of the Contract with America. The laws that eventually passed made narrow modifications.

During the next decade, the government made little progress on Galloway’s recommendations. FEMA shut down a program that relocated or demolished erosion-threatened structures. In 1999, Congress directed the Army to create a plan for the Upper Mississippi River basin, but the Corps scaled back so much that the study left out most of what would be the hardest-hit areas during the 2008 floods. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, FEMA instituted several reforms on disaster response, but few to prevent flood damage. The 2007 National Levee Safety Program Act didn’t provide enough funding for an overhaul.

Inside the Beltway, the 2008 Midwest floods generated little beyond talk. As the Congressional Research Service dryly concluded in a recent report on flooding, “The fundamental direction and approach of the national policies and programs remain largely unchanged since 1993.”

Billions of dollars in federal money remain available for levees and other structural anti-flooding measures. But for states and cities like Vermont and Charlotte that want to prevent flooding without building, funding is more limited. The USDA authorized $145 million for floodplain easements as part of the economic stimulus package, enough for half the applications it received.

“I’d still argue, and I don’t see it changing anytime soon, that there’s no mechanism in place within the federal programs to reward avoidance,” Vermont floodplain manager Evans says.

And flood protection isn’t getting much attention from the American public.

“Given everything that’s going on with the economic crisis and wars, people just turn off after awhile. It’s overload,” says Stephanie Lindloff, a senior director at the conservation organization American Rivers. “There’s a sense, and it’s unfortunate, that when there’s the next natural disaster — a hurricane or a levee failure or something like a major flood event — that that might bring these issues more to light.”

Kline marches us across an arc-shaped parcel in Rochester that houses a baseball field, a skate park and a school. In the distance, verdant mountains surround white A-frame homes, with fields of corn at river’s edge. It’s the polar opposite of the horrific island in Bennington. This isn’t a landscape — it’s a Winslow Homer painting.

Despite the baking-hot, late-afternoon sun, Kline is bounding down the field toward the riverbed. This farmland is one of the first 10 plots of Vermont’s innovative easement program, in which a state land trust purchases channel management rights to a narrow corridor lining a river. Instead of spending money to armor the riverbank against erosion, the farmer gets cash (say, $1,500 per acre), and the state receives authority to enforce the river’s ability to move where it wants. Kline is working to acquire dozens more plots just like this.

Though protecting agricultural land is a worthy cause, a key motive behind the easements is to save towns from floods. In Hinesburg, a bedroom suburb of Burlington, the La Platte River flows down out of the mountains and hits a large floodplain where condominium developers were itching to buy land. River Management negotiated an easement that re-established the floodplain, helping to protect the village from violent flows.

Such one-off projects only hint at Kline’s more ambitious plans. He’s trying to integrate national flood insurance with the river erosion hazard maps in every town in Vermont. He’s using incentives to persuade local officials to change: Those who follow state recommendations jump to the front of the line for federal grants. He’s working with the Legislature to create parallel policies at other agencies that reward proactive towns.

Now that New Hampshire has followed his lead, he’s also hoping to assemble a northeast regional river management partnership that’ll capture the interest of the federal government, which, he hopes, will add its own incentives. He and Evans are already pushing FEMA to increase federal matching grants for cities and states that go well beyond minimum regulations.

“Without a better package of incentives for communities, I…” Kline begins, then stops and sighs.

“We worry that we’ll be sort of stuck in first gear. Little old Vermont has a hard time making a big dent at the national level. The federal government could play a huge role.”

Kline looks out across the field to the other bank, surveying the rows of corn in the purple dirt. Whoever owns this land, or leases it, can grow corn only up to a 50-foot buffer against the river, wherever it may move. As long as the buffer is in place, it’s his land. But if a flood scoops a chunk out of the cornfield, it’s now the river’s property, and the farmer must retreat.

“The whole corridor now belongs to the river,” he says. “And you are a guest of the river.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.