Robots had a mixed reputation in the early 1930s. They represented the promise of streamlined, modern living that was supposed to be just around the corner. But the robot also symbolized the rise in automation, a source of terrifying insecurity within the U.S. labor market during the Great Depression.

The robot became a tragic symbol among live musicians who were displaced during this time, as recorded music swept into movie theaters. A story about a robot rising up and shooting its inventor even made the rounds in American newspapers in 1932—a story many could believe since technology seemed to be progressing at a stupefying pace.

The consensus seemed to be it was just a question of when (not if) humanoid robots would become an integral part of modern domestic life. (As Baxter demonstrates, we’re still asking that question.)

While stories of robots “learning” to do fantastical things were common in the 1930s, there were few explanations in the popular press about precisely how robots worked. But the July 1931 issue of Radio-Craft magazine showed amateur inventors and tinkerers how to make their very own humanoid robot.

The magazine included an article about Paul Von Kunits, a radio engineer in New York who had made his own “Iron Man” or “Mr. Radio Robot.” The word robot was little more than a decade old, but already inventive people like Von Kunits were creating novelty robots that could appear to stand up, talk and even fire a gun. It turns out that the story of a sentient— trigger-happy—robot from 1932 was in reality a minor accident involving an inventor in England whose gun went off prematurely, giving him a powder burn during his robot demonstration.

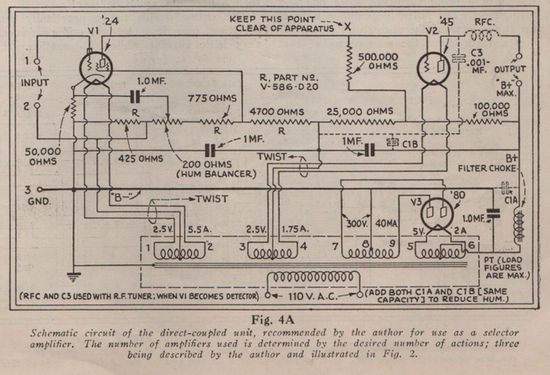

Some of the most famous robots of the 1930s, including Westinghouse’s Elektro at the 1939 New York World’s Fair in New York, were said to respond to the human voice. It’s fascinating to see detailed descriptions in this issue of Radio-Craft of how this response was achieved using 1930s technology. Detailed schematics and descriptions showed how you could manipulate a robot through push-buttons, but also how you might get Iron Man to “react” to different tones of voice as they fed through a microphone.

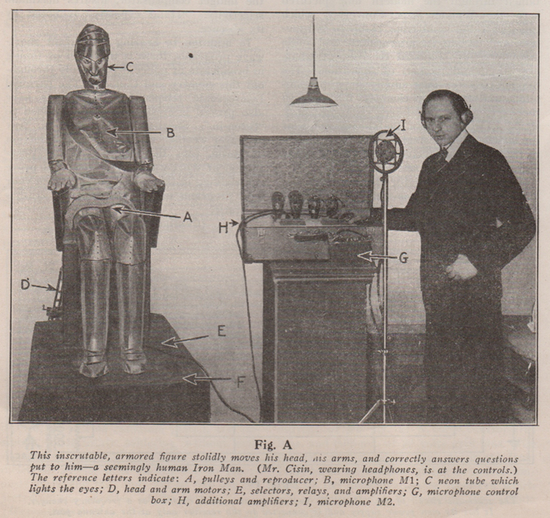

Mr. Cisin at the controls of the robot (July 1931 Radio-Craft magazine)

The shell of Iron Man was a costume for a medieval knight, which the article assures us was purchased at a reasonable rate. The photograph above lists some of the necessary components, including pulleys (which allowed you to move the robots arms), microphones, neon tubes, motors, amplifiers, and so on. Below is an example of one of the 10 schematics included with the article, showing how to configure the basic electronics of the Iron Man.

Schematic 4a showing how to construct some of the electronics for Iron Man

Much like Elektro, Von Kunits’ Iron Man didn’t have much practical purpose aside from entertaining at fairs or advertising in shops. Elektro did find a second life after WWII when “he” toured appliance stores in the 1950s to hawk dishwashers and refrigerators. In a similar fashion, the Iron Man was leased to a large furniture store on 57th Street in 1931. He spent a month “answering” questions for shoppers and playing music from phonograph records.

While the article insists he became a popular vaudeville star, the Iron Man has been overshadowed in 20th century tech history by more popular robots of the 1930s like Elektro and even Alpha. Show business can be cruel to both man and machine.