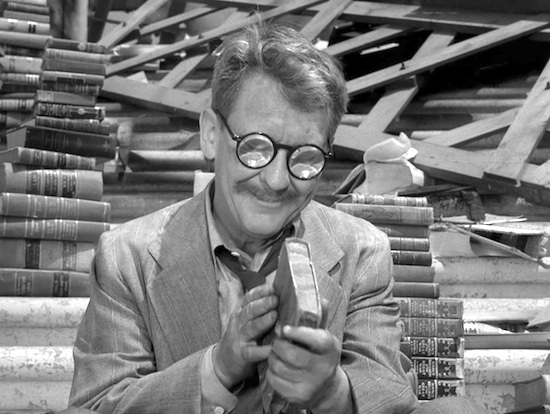

Screenshot from the 1959 episode of The Twilight Zone, “Time Enough At Last”

While visiting my parents in Minnesota a couple of weeks ago my dad excitedly showed me his new iPad mini and all the media he purchased for it. A couple episodes of Alfred Hitchock Presents, a few episodes of Twilight Zone… perhaps unsurprisingly my dad and I have similar taste in old TV shows.

But as he was showing me his new toy he wondered aloud, “So what happens to all this media when I die? How do I pass it on to you and your brothers?”

“You can’t,” I said matter of factly, knowing he already had an inkling about the answer.

“But they’ve got to fix that, right? They’re going to fix that.”

“I wouldn’t be so sure,” I replied. “The companies who control that don’t think it needs fixing.”

The TV shows he purchased are protected by Apple’s digital rights management (DRM) code that restricts how the media you’ve legally purchased can be used and shared. Unlike a DVD of those TV shows that my dad could lend me by physically handing it to me, there’s no easy way for him to let me borrow (or inherit) the media he legally purchased on iTunes.

When you buy a book, do you own it? Or are you merely renting it from the publisher under a license that allows you to read it? This is the question of our age as the resale (and even sharing) of digital goods like ebooks and digital music is nearly impossible under most publishers’ terms. But what if it’s a dead-tree book? Do I have the right to resell a pulp and paper book that I purchased? Or does the publisher retain certain rights to how I might resell the work?

The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments this past October in the case ofKirtsaeng v. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. which may very well have an impact on whether you “own” the copyrighted works you purchase. The long and short of it is that a Thai student (Kirtsaeng) who was studying in the U.S. had textbooks shipped from his family in Thailand, where textbooks are much cheaper. Kirtsaeng was then reselling them in the U.S. at a mark-up, making more than $100,000 in the process. Textbook publisher Wiley then sued him for copyright infringement. Wiley says, essentially, that its copyright was violated as soon as those books crossed into the U.S. because they were not lawfully made under title of the Copyright Act. The case hinges on the interpretation of “lawfully made under this title.”

Kirtsaeng is hanging his hat on what’s known as the first sale doctrine, first recognized in 1908 and then established in Section 109 of the Copyright Act, which limits the rights of publishers to control their work after it’s been sold to a consumer. Essentially, once you buy a CD or a book or any other work in a fixed medium that’s protected under copyright law you’re free to sell that work without having to ask the copyright holder for permission or give them any form of compensation.

But some people have never been happy with the first sale doctrine and believed that in the future artists would have more say in how their work was used or sold long after first sale. The 1976 book Future Facts by Stephen Rosen looks at various 1970s trends and attempts to project what life will look like in the future. One of those “future facts” is that one day artists would be able to collect royalties on their works long after they’ve been sold to a buyer the first time.

From the 1976 book Future Facts:

Artists are pressing for national legislation that will compel collectors who sell their work at a profit to pay them a percentage of that profit.

Practitioners in many branches of the creative arts are paid a basic fee for their efforts, plus a royalty or residual if their work is used again. Motion picture, television and radio artists generally work on such a basis, and so do composers and many writers. Moreover, they support guilds and unions that enforce their rights vigorously. By contrast, most visual artists are unorganized and their rights are unprotected. Sculptors, painters and printmakers, who sell their work to collectors, normally don’t receive another cent, although the collectors may sell the work at substantial profits.

This inequitable situation is finally starting to change. A few artists, who hope for a percentage of any profit realized on resale of their work, are getting it. An advocate of the right of artists to subsequent payments is a New York accountant, Rubin Gorewitz. He and others have drawn up a bill for passage by Congress that would apply to all profits on the resale of work by living artists. Under this bill, whenever the artist’s work is resold, the collector would pay him 15 percent of the profit. The artist would supply a certificate vouching for the authenticity of the work, and the seller would give a copy to the buyer. If the buyer wished to insure the work, he would present the certificate to his insurance company as proof of its origin. Legislators have indicated they will give this proposal their serious attention.

“All parties would profit to some extent,” declares accountant Gorewitz. “The artist would receive his royalty; the buyer would be assured of the genuineness of the work; the insurance company’s risk of theft would be reduced; and the seller’s profit would be only a slightly reduced one.”

It’s easy to understand the frustrations of Rosen and other artists of the 1970s here, especially since the Gorewitz-depicted future never arrived. But the first sale doctrine is generally seen as a positive aspect for consumers in copyright law. Once you legally acquire a copyrighted work you have the right to resell or lend out that work without having to get permission from the copyright holder. Fundamentally this is seen as a good way to encourage the spread of information and actually increases the value of the work in its first sale since the buyer knows that they can resell it later. If reselling a copyrighted work were illegal (or de facto illegal in the case of DRM) it decreases my willingness to spend much money on it since I’m not able to recoup any of my original investment in that copyrighted work.

In the case of textbooks imported internationally, we’ll see shortly whether the court finds that the first sale doctrine applies. But in the case of classic TV episodes legally purchased through services like iTunes, we may have a much longer wait to see if the first sale doctrine has any bearing in the digital age.